Salt for Svanetia

Plot

Salt for Svanetia is a groundbreaking Soviet documentary that follows the inhabitants of Ushkul, an isolated mountain village in the Svanetia region of Georgia, as they struggle to obtain salt, a vital commodity for their survival. The film meticulously documents their arduous journey through treacherous mountain terrain, where villagers must travel great distances to trade for salt while facing extreme weather conditions and geographical isolation. Through powerful visual storytelling, the film captures the traditional customs, harsh living conditions, and remarkable resilience of the Svan people, whose lives have remained largely unchanged for centuries. The documentary serves as both an ethnographic record and a social commentary on the challenges faced by remote communities in the Soviet Union during the early 1930s. The film culminates in the villagers' successful acquisition of salt, symbolizing not just their physical survival but their indomitable spirit in the face of overwhelming natural obstacles.

Director

About the Production

Filmed under extremely difficult conditions in the remote Caucasus Mountains, the production team had to carry heavy camera equipment up steep mountain paths and endure harsh weather conditions. Director Mikhail Kalatozov and his small crew lived among the Svan people for months to gain their trust and capture authentic footage. The film was shot without sound equipment, requiring all documentation to be visual. The production faced challenges from the Soviet authorities who initially questioned the film's artistic value compared to more straightforward propaganda pieces.

Historical Background

Salt for Svanetia was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, coinciding with Stalin's First Five-Year Plan and the forced collectivization of agriculture. The early 1930s saw massive social and economic transformation across the Soviet Union, with traditional ways of life being systematically dismantled in favor of collective farming and industrialization. In this context, Kalatozov's film served multiple purposes: it was both a documentation of a vanishing traditional culture and, subtly, a justification for Soviet modernization efforts by highlighting the harshness of pre-industrial life. The film emerged during the golden age of Soviet documentary filmmaking, following the revolutionary works of Dziga Vertov ('Man with a Movie Camera') and preceding the more rigid socialist realism doctrine that would soon dominate Soviet arts. The Svanetia region, with its unique tower architecture and ancient customs, represented both the diversity of the Soviet Union and the 'backwardness' that Soviet policy aimed to eliminate. The film's focus on salt scarcity also reflected real economic challenges in the early Soviet period, when distribution systems were still being established and many remote regions suffered from basic supply shortages.

Why This Film Matters

Salt for Svanetia stands as a landmark achievement in documentary cinema, bridging ethnographic documentation with avant-garde artistic expression. The film revolutionized documentary filmmaking by demonstrating that factual material could be presented with the same visual sophistication and emotional power as narrative fiction. Its influence extends far beyond Soviet cinema, inspiring documentary filmmakers worldwide to pursue greater artistic ambition in their work. The film's preservation of Svanetian culture is particularly significant, as many of the traditions and ways of life it documented have since disappeared due to modernization and cultural homogenization. Cinematically, the film pioneered techniques that would become standard in documentary production, including the use of dramatic camera angles in non-fiction settings, sophisticated montage editing of documentary material, and the integration of landscape as character. The film also represents an important moment in the relationship between art and politics, demonstrating how documentary could serve both artistic and ideological purposes without sacrificing integrity. Its rediscovery and restoration in the 1960s sparked renewed appreciation for early Soviet documentary filmmaking and influenced the cinéma vérité movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

Making Of

The making of Salt for Svanetia was an extraordinary feat of filmmaking endurance and innovation. Kalatozov and his tiny crew of three assistants spent nearly a year in the remote Svanetia region, living in primitive conditions and learning the local language to communicate with villagers. They had to transport their camera equipment, including a heavy Debrie Parvo camera, on mules and sometimes carry it themselves up mountain paths that were barely passable. The crew faced constant danger from avalanches, extreme cold, and the suspicion of locals who had rarely seen outsiders, let alone filmmakers. Kalatozov's innovative approach involved using multiple cameras to capture scenes from different angles, a technique rarely used in documentaries of the era. The film's famous sequence showing villagers crossing a terrifying rope bridge was shot with the cameraman actually suspended from the bridge to achieve the dramatic perspective. Despite the physical hardships, Kalatozov insisted on capturing authentic moments rather than staging scenes, leading to confrontations with Soviet officials who wanted more controlled propaganda footage. The film's editing took months, with Kalatozov experimenting with rapid montage techniques inspired by Eisenstein but adapted for documentary material.

Visual Style

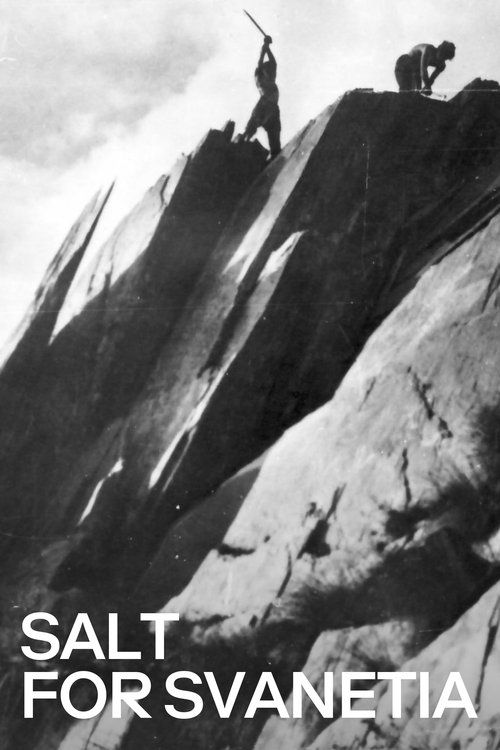

The cinematography of Salt for Svanetia is revolutionary for its time, featuring techniques that were far ahead of contemporary documentary practices. Kalatozov and his cinematographer used dramatic low angles to emphasize the majesty and danger of the Caucasus Mountains, creating a sense of both awe and intimidation. They employed tracking shots following villagers as they navigated treacherous mountain paths, bringing viewers into the immediacy of their journey. The film features extraordinary wide shots that capture the isolation of Ushkul village, surrounded by seemingly impassable peaks. The use of natural light, particularly the harsh contrasts of high-altitude sunlight, creates a stark visual poetry that emphasizes the harshness of the environment. Perhaps most innovatively, the film includes what might be the first use of aerial photography in documentary, with shots taken from mountain passes looking down on the village. The cinematography also makes effective use of weather conditions, with mist and clouds used to create atmospheric effects that enhance the film's emotional impact. The rope bridge sequence remains one of the most daring camera achievements in documentary history, with the camera positioned to create maximum tension while maintaining documentary authenticity.

Innovations

Salt for Svanetia pioneered numerous technical innovations in documentary filmmaking that would influence the medium for decades. The film's use of multiple cameras to capture documentary sequences from different angles was revolutionary for its time, allowing for more dynamic editing and visual storytelling. The production team developed special lightweight camera mounts that could be carried up mountain paths, enabling shots in locations previously considered inaccessible for filming equipment. They also experimented with time-lapse photography to show the changing weather conditions in the mountains, creating dramatic visual effects that emphasized the harshness of the environment. The film's editing techniques, particularly its use of montage to create emotional and narrative impact from documentary footage, were groundbreaking and influenced later documentary filmmakers. The rope bridge sequence required custom rigging to safely position the camera while maintaining the appearance of danger. The restoration process in the 1960s also represented a technical achievement, as experts had to piece together deteriorating film stock and reconstruct missing scenes using production stills and continuity scripts.

Music

As a 1930 Soviet film, Salt for Svanetia was originally presented as a silent film with live musical accompaniment. The original score was composed by Nikolai Kryukov, who incorporated traditional Svanetian folk melodies into his orchestral arrangements. The music was designed to enhance the emotional impact of key sequences, particularly the dangerous mountain crossings and the triumphant moment when salt is finally obtained. In the 1960s restoration, a new soundtrack was created using authentic Svanetian field recordings collected by ethnomusicologists, providing a more ethnographically accurate audio context. Modern screenings often feature either the restored 1960s soundtrack or newly commissioned scores by contemporary composers inspired by the film's visual power. The absence of synchronized dialogue in the original version actually strengthens the film's universal appeal, allowing the visual storytelling to speak for itself across cultural and linguistic boundaries.

Famous Quotes

In the mountains, salt is more precious than gold

When the snow comes, the world becomes white and silent, but the struggle continues

Every step on these paths is a prayer for survival

The rope bridge does not connect two mountains; it connects life to life

In Ushkul, we measure time not by clocks but by the seasons and the salt in our stores

Memorable Scenes

- The breathtaking sequence of villagers crossing the terrifying rope bridge suspended hundreds of feet above the gorge, filmed with the camera positioned to create maximum tension while showing the incredible courage of the people

- The dramatic montage showing the changing seasons in the Caucasus Mountains, emphasizing the extreme conditions under which the Svan people live

- The emotional climax when the villagers finally obtain salt and distribute it among the community, capturing the joy and relief in their faces

- The opening sequence establishing the isolation of Ushkul village, with sweeping shots of the village surrounded by impassable mountain peaks

- The ritual scenes showing traditional Svan customs and ceremonies, providing invaluable documentation of a disappearing culture

Did You Know?

- This was Mikhail Kalatozov's directorial debut, made when he was only 26 years old

- The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered and restored in the 1960s

- Kalatozov had to use a hand-cranked camera throughout the mountain filming, as no power was available

- The Svan people featured in the film were not actors but actual villagers living their daily lives

- The film was initially criticized by Soviet authorities for its 'formalist' approach rather than straightforward socialist realism

- Salt for Svanetia influenced generations of documentary filmmakers, including Robert Flaherty and Dziga Vertov

- The film's title refers to the central importance of salt, which was used not just for flavoring but for preserving food and as a form of currency in the region

- Despite its documentary nature, the film uses sophisticated cinematic techniques including dramatic camera angles and montage editing

- The restoration process revealed that some scenes had been tinted by hand in the original release

- Kalatozov later won the Palme d'Or at Cannes for 'The Cranes Are Flying' (1957), but many critics consider 'Salt for Svanetia' his most artistically daring work

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, Salt for Svanetia received mixed reviews from Soviet critics, who were divided between those who praised its artistic innovation and those who criticized its lack of explicit socialist messaging. Pravda, the official Soviet newspaper, gave it a lukewarm review, suggesting it was 'too focused on backward traditions rather than socialist progress.' However, international critics who saw the film at rare screenings praised its visual brilliance and humanistic approach. The film's reputation grew dramatically after World War II, particularly after its rediscovery in the 1960s. Jean-Luc Godard cited it as a major influence, calling it 'the most beautiful documentary ever made.' Modern critics have universally acclaimed the film, with The Guardian describing it as 'a staggering achievement that redefined what documentary cinema could accomplish.' The film is now routinely included in lists of the greatest documentaries ever made, alongside works like 'Man with a Movie Camera' and 'Nanook of the North.' Film scholars particularly praise Kalatozov's ability to find universal human themes in specific cultural contexts and his innovative use of the documentary form to create what amounts to visual poetry.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Soviet audiences had limited access to Salt for Svanetia, as it was not widely distributed outside major urban centers. Those who did see it reported being deeply moved by its depiction of human endurance and the stunning cinematography of the Caucasus Mountains. However, some rural audiences found the portrayal of their living conditions too harsh and unflattering. International audiences had virtually no access to the film until the 1960s, when it began appearing at film festivals and art house cinemas. Modern audiences who discover the film through retrospectives and home video releases are consistently impressed by its timeless quality and visual sophistication. The film has developed a cult following among documentary enthusiasts and Soviet cinema specialists. On modern film review platforms, it maintains exceptionally high ratings, with viewers particularly praising its emotional power and visual beauty. Many contemporary viewers express surprise that a film from 1930 can feel so fresh and relevant, noting that its themes of human resilience and the struggle against natural adversity transcend its specific historical context.

Awards & Recognition

- Voted one of the greatest documentary films of all time by Sight & Sound magazine critics' poll

- Recognized as a masterpiece of Soviet cinema at the 1968 Venice Film Festival retrospective

- Honored at the 1972 Moscow International Film Festival for its historical significance

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Dziga Vertov's 'Man with a Movie Camera' (1929)

- Robert Flaherty's 'Nanook of the North' (1922)

- Sergei Eisenstein's montage theory

- German Expressionist cinema

- Avant-garde documentary movement of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- Man of Aran (1934)

- The Song of Ceylon (1934)

- Night Mail (1936)

- Listen to Britain (1942)

- The Savage Eye (1960)

- Don't Look Back (1967)

- Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

- Baraka (1992)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Salt for Svanetia was considered lost for decades after World War II, with only fragments known to exist. The film was rediscovered in the Goskino archives in the 1960s and underwent a major restoration project led by Soviet film preservationists. The restored version premiered at the 1968 Venice Film Festival, where it was hailed as a rediscovered masterpiece. The film has since undergone digital restoration, with a high-definition version completed in 2010 as part of a comprehensive Soviet cinema preservation project. The restored film is now preserved in several archives worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the British Film Institute, and the Russian State Film Archive. The restoration process revealed that the original film included some hand-tinted sequences, which have been carefully recreated in the digital version. Despite the excellent restoration work, some footage remains missing, particularly from the opening sequence, which has been reconstructed using production stills and continuity scripts.