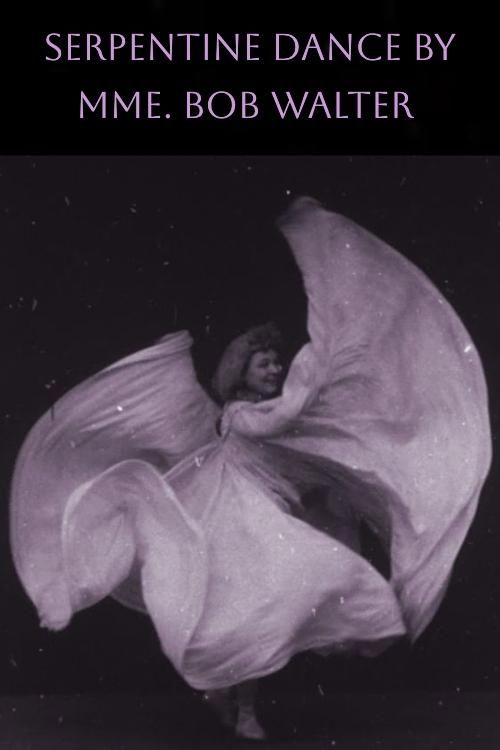

Serpentine Dance by Mme. Bob Walter

Plot

This early cinematic gem captures Mme. Bob Walter performing the mesmerizing serpentine dance, a popular performance art of the late 19th century. The film documents her graceful movements as she manipulates long, flowing silk fabrics that create stunning visual effects through her choreography. The dancer's flowing robes create optical illusions as they swirl and undulate around her body, enhanced by the primitive yet effective lighting techniques of early cinema. The entire performance showcases the intersection of dance, visual art, and emerging motion picture technology in a brief but captivating display. Alice Guy-Blaché's camera captures the ethereal quality of the dance, preserving this artistic moment for future generations.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed using early hand-cranked camera equipment, this short represents Alice Guy-Blaché's innovative approach to capturing performance art on film. The production likely utilized theatrical lighting techniques adapted for the new medium of cinema. The film was shot on 35mm film stock, which was the standard format of the period. As one of Gaumont's early productions, it was created during the company's formative years under Léon Gaumont's leadership. The serpentine dance required special consideration for lighting to maximize the flowing effects of the fabric, demonstrating early understanding of cinematographic principles.

Historical Background

The year 1897 marked a pivotal moment in cinema history, occurring just two years after the Lumière brothers' first public screening and one year after Georges Méliès began his filmmaking career. This period saw the rapid development of film as both a technological marvel and an artistic medium. France was at the center of this cinematic revolution, with companies like Gaumont and Pathé pioneering film production and distribution. The late 1890s also witnessed the height of the Belle Époque, a period of cultural flourishing in France that celebrated artistic innovation and performance arts. The serpentine dance itself represented the era's fascination with movement, light, and visual spectacle, reflecting broader cultural interests in spiritualism, exoticism, and new forms of artistic expression. Women were increasingly visible in public performance arts, making Alice Guy-Blaché's role as a female director particularly significant.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest examples of a female director capturing female performance on camera. Alice Guy-Blaché's work represents a crucial chapter in cinema history that has often been overlooked in traditional film narratives. The serpentine dance itself was an important cultural phenomenon, representing the intersection of art, technology, and changing social norms regarding women's public performance. The film serves as an early example of dance documentation, predating the establishment of dance film as a genre by decades. It also demonstrates how early cinema adapted popular theatrical and vaudeville acts for the new medium, helping to establish the language of cinematic performance. The preservation of such early works provides invaluable insight into the aesthetics and techniques of cinema's formative years, while also highlighting the significant contributions of women to film history from its very inception.

Making Of

Alice Guy-Blaché, working as Gaumont's head of production, was responsible for creating numerous short films featuring popular entertainments of the day. The serpentine dance was particularly suitable for early cinema as its flowing movements and visual effects translated well to the new medium. The filming would have required careful coordination between the performer and camera operator, as early cameras had limited capacity and required manual cranking. The lighting setup was crucial, as the serpentine dance relied on dramatic illumination to create its signature effects. Mme. Bob Walter would have been a professional dancer familiar with adapting her performance for the camera's limitations. The production likely took place in Gaumont's early studio facilities in Paris, which were among the first dedicated film production spaces in the world.

Visual Style

The cinematography of this 1897 film reflects the primitive but effective techniques of early cinema. Shot on 35mm film using hand-cranked cameras, the film employs a static camera position typical of the period, framing the full body of the performer to capture her complete movements. The lighting would have been adapted from theatrical techniques, using footlights and colored gels to create the dramatic effects essential to the serpentine dance. The camera work demonstrates an understanding of how to best capture flowing movement within the limitations of early equipment. Some versions of these early serpentine dance films were hand-colored, frame by frame, to enhance their visual impact. The cinematography prioritizes clarity of movement over artistic composition, reflecting the primary goal of early dance films: to document and preserve the performance for audiences who might not otherwise see it.

Innovations

While technically simple by modern standards, this film represents several important achievements in early cinema. The successful capture of flowing movement and fabric effects demonstrated early cinematographers' growing understanding of how to translate three-dimensional performance to the two-dimensional film medium. The lighting techniques employed to enhance the serpentine dance's visual effects showed innovation in adapting theatrical lighting for the new medium of cinema. The film's very existence as a product of a female director in 1897 was a significant achievement in an industry that would soon become male-dominated. The preservation of dance movement on film represented a major step forward in documentation capabilities, allowing performances to be seen beyond their original live contexts. The technical execution, while basic, successfully captured the essential qualities that made the serpentine dance popular, proving that early cinema could effectively preserve and transmit artistic performance.

Music

As a silent film from 1897, this work had no synchronized soundtrack. However, during its original exhibition periods, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate music to complement the dance. The musical accompaniment would likely have consisted of popular salon music or classical pieces that matched the graceful, flowing nature of the serpentine dance. The choice of music could vary depending on the venue and the musicians available, ranging from simple piano arrangements to more elaborate orchestral scores in larger theaters. The live musical element was crucial to the viewing experience, providing emotional context and rhythm to enhance the visual performance. In modern presentations, the film is often accompanied by period-appropriate music or contemporary scores composed specifically for silent film exhibitions.

Memorable Scenes

- The entire film consists of a single memorable scene: Mme. Bob Walter performing the serpentine dance, her flowing silk robes creating mesmerizing patterns as she moves gracefully across the frame, the fabric catching the light in waves of color and shadow, embodying the ethereal beauty that made this dance form so popular in the Belle Époque era.

Did You Know?

- Alice Guy-Blaché is considered the first female film director in history, making this film one of the earliest directed by a woman

- The serpentine dance was made famous by American dancer Loïe Fuller, who patented her lighting techniques for the performance

- This film is part of Alice Guy-Blaché's early work at Gaumont, where she was head of production from 1896 to 1906

- The serpentine dance was one of the most frequently filmed subjects in early cinema, with multiple versions created by different pioneers

- Mme. Bob Walter was one of several performers who specialized in the serpentine dance during the 1890s

- The film was likely hand-colored in some versions, a common practice for early dance films to enhance their visual appeal

- This represents an early example of dance documentation on film, predating the establishment of dance as a film genre

- The serpentine dance performances were considered quite scandalous by some Victorian-era audiences due to the revealing nature of the flowing costumes

- Alice Guy-Blaché made over 700 films in her career, but only about 350 survive today

- The film was created just two years after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening in 1895

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of early films like this was limited, as film criticism as a profession had not yet developed. However, these serpentine dance films were generally well-received by audiences and exhibitors for their visual appeal and technical novelty. Modern film historians and critics recognize this work as significant for several reasons: its documentation of Alice Guy-Blaché's pioneering role as a female director, its representation of popular performance arts of the era, and its place in the development of cinematic techniques for capturing movement and light. The film is now studied in academic contexts for its historical importance and as an example of early cinema's approach to documenting performance art. Critics today appreciate the film not just for its historical value but also for its aesthetic qualities, particularly the way it captures the ethereal beauty of the serpentine dance despite the technical limitations of the period.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences of the 1890s were fascinated by films featuring the serpentine dance due to their visual spectacle and the novelty of seeing movement captured on film. These short dance films were popular attractions in early film exhibitions, often shown alongside other brief actualities and trick films. The combination of the flowing costumes, dramatic lighting effects, and the novelty of recorded movement made these films particularly appealing to turn-of-the-century audiences. The serpentine dance's somewhat daring nature, with its flowing and occasionally revealing costumes, added to its appeal for audiences seeking entertainment that pushed against Victorian propriety. Modern audiences viewing this film today typically approach it from a historical perspective, appreciating its significance as an early cinematic document and as evidence of women's early contributions to filmmaking.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Loïe Fuller's serpentine dance performances

- Theatrical dance traditions

- Vaudeville entertainment

- Stage lighting techniques

This Film Influenced

- Other serpentine dance films by early pioneers

- Early dance documentation films

- Alice Guy-Blaché's subsequent performance films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved in various film archives, including collections dedicated to early cinema and Alice Guy-Blaché's work. The film exists in the archives of major institutions such as the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. Some versions may be hand-colored, representing different preservation states of early film prints. The film has been digitized as part of efforts to preserve and make accessible early cinema works.