Sightseeing Through Whisky

Plot

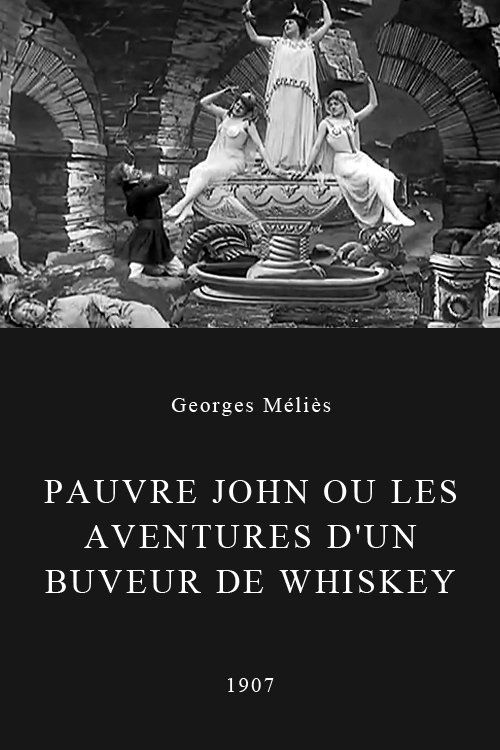

In this Georges Méliès comedy, John is an enthusiastic member of a sightseeing tour group, but his love for whisky proves to be his downfall. As the group explores ancient ruins, John becomes increasingly intoxicated and unable to keep up with his fellow tourists. Left behind at the archaeological site, the drunken man begins experiencing vivid hallucinations that transform the ruins around him into fantastical visions. Through Méliès's signature special effects, the stone structures morph and dance, creating a surreal landscape that reflects John's alcohol-induced delirium. The film serves as both a cautionary tale about excessive drinking and a showcase for early cinematic magic.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was created using Méliès's innovative substitution splice technique and multiple exposure effects. The ruins were likely constructed as detailed set pieces in Méliès's glass studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, allowing for precise control over the special effects. The production would have required careful choreography of the actors' movements to synchronize with the mechanical effects and transformations.

Historical Background

This film was created during a pivotal period in cinema history when the medium was transitioning from novelty to art form. In 1907, the film industry was rapidly professionalizing, with companies like Méliès's Star Film competing against emerging studios. The year also saw the formation of the first film exchange in the United States and the growing dominance of American cinema internationally. Méliès, once the undisputed king of cinematic fantasy, was facing increasing competition from filmmakers who were developing more realistic narrative styles. This film reflects both the era's fascination with modern tourism and the social concerns of the temperance movement, which was gaining momentum in many Western countries.

Why This Film Matters

'Sightseeing Through Whisky' represents an important example of early narrative cinema that combined entertainment with social commentary. The film demonstrates how Méliès used his magical techniques not just for fantasy but to explore psychological states, predating surrealist cinema by nearly two decades. It also reflects the early 20th-century preoccupation with the effects of alcohol on society, a theme that would become increasingly common in cinema as the temperance movement gained political power. The film's use of hallucination sequences influenced later filmmakers exploring altered states of consciousness and remains a testament to Méliès's role as a pioneer of cinematic language.

Making Of

The production of 'Sightseeing Through Whisky' took place in Méliès's elaborate glass-walled studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois, which allowed him to control lighting precisely for his special effects. The drunk character's hallucinations were achieved through a combination of multiple exposures, substitution splices, and mechanical stage effects. Méliès would have painted the sets himself, as he was a skilled artist and designer. The actors, particularly Fernande Albany, would have needed to perform with exaggerated gestures typical of early cinema to convey the story without dialogue. The filming process was painstaking, with each special effect requiring precise timing and multiple takes to perfect the illusion of transformation.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects Méliès's theatrical approach to filmmaking, with a fixed camera position reminiscent of a theater audience's perspective. The camera work is straightforward, allowing the elaborate special effects to take center stage. The film uses multiple exposure techniques to create the hallucination sequences, with careful masking and timing to achieve the supernatural transformations. The lighting would have been controlled through the glass studio design, creating the dramatic shadows and highlights characteristic of Méliès's visual style.

Innovations

The film showcases several of Méliès's pioneering technical innovations, including the substitution splice (cutting and replacing objects between frames), multiple exposure techniques, and sophisticated mechanical effects. The transformation sequences required precise timing and careful planning, demonstrating Méliès's mastery of the medium's technical possibilities. The film also represents an early example of using special effects to represent psychological states rather than purely magical phenomena, expanding the narrative potential of cinematic effects.

Music

As a silent film, 'Sightseeing Through Whisky' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original exhibition. The score would likely have been provided by a pianist or small orchestra in the theater, playing popular tunes of the era or classical pieces appropriate to the film's changing moods. For the drunken sequences, musicians might have employed comic or dissonant music to enhance the humorous effect. In some venues, sound effects might have been created manually to accompany the visual transformations.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue was featured in this silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where the ancient ruins begin to transform and dance around the drunken protagonist, showcasing Méliès's signature special effects and creating a surreal landscape that represents the character's alcohol-induced hallucinations

Did You Know?

- This film was released by Méliès's Star Film Company and was cataloged as number 983-985 in their production list

- The film showcases Méliès's mastery of the substitution splice technique, which he pioneered and used extensively in his work

- Fernande Albany, one of the featured performers, was a regular collaborator with Méliès and appeared in many of his films between 1905-1912

- The title reflects the early 20th-century fascination with tourism and the growing concern about alcoholism in society

- Like many Méliès films, it was hand-colored in some releases, a labor-intensive process that added to the magical quality of the visuals

- The film was distributed internationally, with versions created for both European and American markets

- The hallucination sequences demonstrate Méliès's theatrical background, with influences from stage magic and Parisian café-concert traditions

- This film was part of Méliès's later period when he was producing shorter, more commercially-focused films to compete with emerging cinema styles

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of Méliès's films from this period were generally positive, with critics praising his technical innovations and entertaining storytelling. Trade publications of the era noted the film's clever use of special effects and its humorous take on a serious social issue. Modern film historians recognize 'Sightseeing Through Whisky' as a significant example of Méliès's later work, demonstrating his continued creativity even as his commercial dominance was waning. The film is now appreciated for its sophisticated visual storytelling and its role in the development of cinematic special effects.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th-century audiences were reportedly delighted by Méliès's magical transformations and the humorous depiction of drunken hallucinations. The film's combination of visual spectacle and relatable comedy made it popular in both European and American markets. As with many of Méliès's works, it was particularly successful in venues that catered to family audiences and those seeking spectacular entertainment. The film's brevity and visual clarity made it ideal for the mixed programming typical of early cinema exhibitions.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Parisian café-concert entertainment

- Temperance movement literature

- Early 20th-century tourism narratives

This Film Influenced

- Later surrealist films exploring altered states

- Comedy films featuring drunken characters

- Fantasy sequences in narrative cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in archives and has been preserved by film institutions. Prints are held in collections such as the Cinémathèque Française and other major film archives. Some versions may retain the original hand-coloring that was characteristic of Méliès's premium releases.