Sleeping Beauty

Plot

This 1908 French silent adaptation follows the classic tale of Princess Aurora, whose christening is attended by fairies who bestow gifts upon her. However, a wicked fairy, angered at being excluded, curses the princess to die on her sixteenth birthday by pricking her finger on a spindle. A benevolent fairy softens the curse to a hundred-year sleep instead of death. The king orders all spindles burned, but on her sixteenth birthday, the princess discovers an old woman spinning and fulfills the prophecy, falling into a deep sleep along with the entire castle. One hundred years later, Prince Charming learns of the sleeping princess, braves the overgrown castle, and awakens her with true love's kiss, leading to their royal wedding and celebration.

Director

Cast

About the Production

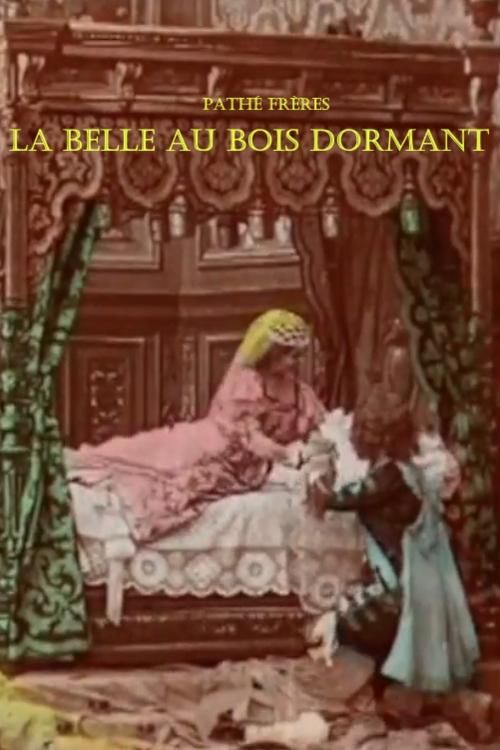

This film was part of Pathé's extensive fairy tale series produced in the early 1900s. The production utilized hand-colored sequences, a common practice for Pathé films of this period, where each frame was meticulously colored by hand using stencils. The film featured elaborate stage sets and props typical of the theatrical influence on early cinema, with painted backdrops creating the fairy tale atmosphere. Multiple cameras were often used simultaneously in this era to create additional distribution prints.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a pivotal period in cinema history when narrative films were beginning to dominate over actualities and trick films. 1908 saw the rise of feature-length films and the establishment of film as a serious artistic medium. The French film industry, particularly Pathé, was the global leader in film production and distribution. This adaptation of a classic fairy tale reflects the growing sophistication of narrative cinema and the industry's recognition of the commercial potential of literary adaptations. The film emerged just before the rise of the Motion Picture Patents Company in America, which would soon change the dynamics of international film distribution. It represents an era when French cultural dominance in cinema was at its peak, before World War I would shift the center of film production to Hollywood.

Why This Film Matters

This early adaptation of Sleeping Beauty represents an important milestone in the development of fantasy cinema and fairy tale adaptations. It demonstrates how early filmmakers recognized the visual potential of classic literature and folklore. The film's existence shows that fairy tales were already considered valuable source material for cinema, a tradition that would continue throughout film history. Its hand-colored nature reflects the early belief that films should be as visually spectacular as possible, treating cinema as a magical medium. The film also exemplifies the transition from cinema as a novelty to cinema as a storytelling art form. As one of the earliest cinematic fairy tales, it helped establish conventions and visual language that would influence countless future adaptations.

Making Of

The production of this 1908 adaptation took place during the golden age of French cinema, when Pathé dominated the global film market. Lucien Nonguet, while not as famous as Méliès, was a skilled director who understood the visual storytelling requirements of silent cinema. Julienne Mathieu's performance relied heavily on exaggerated gestures and facial expressions, as was typical of the period. The hand-coloring process was labor-intensive, requiring teams of women (often young girls) to color each frame individually using stencils. The film's sets were designed to look theatrical, with painted backdrops and minimal three-dimensional elements, reflecting the influence of stage productions on early cinema. The production likely took only a few days to film, as was common for shorts of this era, though the coloring process would have taken weeks longer.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects the stationary camera techniques typical of 1908, with the camera remaining fixed in one position for each scene. The film uses medium shots to capture the actors' performances and full shots to establish the theatrical sets. The lighting was likely natural or basic studio lighting, creating a flat but clear image. The hand-coloring process added visual interest, with particular attention paid to the magical elements and costumes. The cinematographer would have used multiple exposure techniques for any supernatural effects and substitution splices for appearances and disappearances. The visual style emphasizes clarity over complexity, ensuring audiences could follow the story easily.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was its extensive use of the Pathécolor stencil coloring process, which was cutting-edge for 1908. The production likely employed substitution splices for magical effects and multiple exposures for supernatural elements. The sets and props were designed to be visually striking in the new medium of cinema. The film demonstrates early mastery of narrative continuity and scene-to-scene transitions. The intertitles were unusually comprehensive for the period, showing an understanding of cinema's evolving language. The production quality reflects Pathé's position as an industry leader in technical innovation.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. The score would likely have been compiled from popular classical pieces or specially composed music that matched the film's romantic and magical themes. The accompaniment might have included piano, organ, or small ensemble depending on the theater's resources. The music would have emphasized the fairy tale atmosphere, with romantic themes for the princess and prince, dramatic music for the curse, and triumphant music for the awakening and wedding scenes. No original score or cue sheets are known to survive from this production.

Famous Quotes

Thou Shalt Sleep for a Hundred Years

You Have Been a Long Time Coming, prince

The Christening of the Princess

The Prediction Comes True

The Castle of Sleep

Memorable Scenes

- The christening scene where the fairies bestow their gifts and the curse is pronounced

- The princess discovering the spinning wheel and pricking her finger

- The transformation of the entire castle into sleep

- The prince's arrival at the overgrown castle after one hundred years

- The awakening of the princess with true love's kiss

- The final wedding celebration scene

Did You Know?

- Julienne Mathieu, who played the Princess, was one of the most prominent actresses in early French cinema and frequently worked with Georges Méliès

- Director Lucien Nonguet was a collaborator of Georges Méliès and helped direct several of Méliès' famous films

- The film was hand-colored using the Pathécolor stencil process, which was patented in 1905 and used extensively by the company

- This was one of the earliest cinematic adaptations of the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale, predating Disney's version by 51 years

- The intertitles were unusually descriptive for the period, providing clear narrative guidance for audiences

- Pathé Frères was the largest film company in the world at the time of this film's release

- The film was distributed internationally, with English-language versions created for American and British markets

- Special effects were achieved through in-camera techniques, including multiple exposures and substitution splices

- The castle set was likely reused from other Pathé productions, a common cost-saving practice in early cinema

- This film was part of a series of fairy tale adaptations that were extremely popular with audiences of the time

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1908 are scarce, as film criticism was still in its infancy. However, trade publications like The Bioscope and Moving Picture World likely noted the film's elaborate production values and hand-coloring. The film was probably praised for its faithful adaptation of the beloved fairy tale and its visual spectacle. Modern film historians recognize it as an important example of early French fantasy cinema and Pathé's production quality. Critics today appreciate it as a document of early narrative techniques and the transitional period between trick films and story-based cinema. The surviving prints are valued by archivists for their preservation of early hand-coloring techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1908 would have been captivated by the film's magical elements and hand-colored sequences, which were still a novelty. Fairy tale adaptations were extremely popular during this period, as they provided familiar stories that could be enhanced through cinema's visual magic. The film likely performed well commercially, particularly among family audiences. The clear narrative structure and intertitles would have made it accessible to viewers of all ages and literacy levels. Contemporary audiences would have appreciated the spectacle of the transformation scenes and the romantic elements, which were staples of early narrative cinema. The film's success would have encouraged Pathé to produce more fairy tale adaptations.

Awards & Recognition

- None - film awards did not exist in 1908

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charles Perrault's 'La Belle au bois dormant' (1697)

- Brothers Grimm's 'Dornröschen'

- Stage adaptations of the Sleeping Beauty ballet

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Theatrical traditions of fairy tale productions

This Film Influenced

- Walt Disney's 'Sleeping Beauty' (1959)

- Various later silent fairy tale adaptations

- The 1917 'Sleeping Beauty' by Paul Powell

- Modern fantasy films and fairy tale adaptations

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. Some versions retain the original hand-coloring, while others exist only in black and white. Multiple prints with varying degrees of deterioration are held in different film archives worldwide. The film has been digitally restored by several institutions for preservation and accessibility purposes.