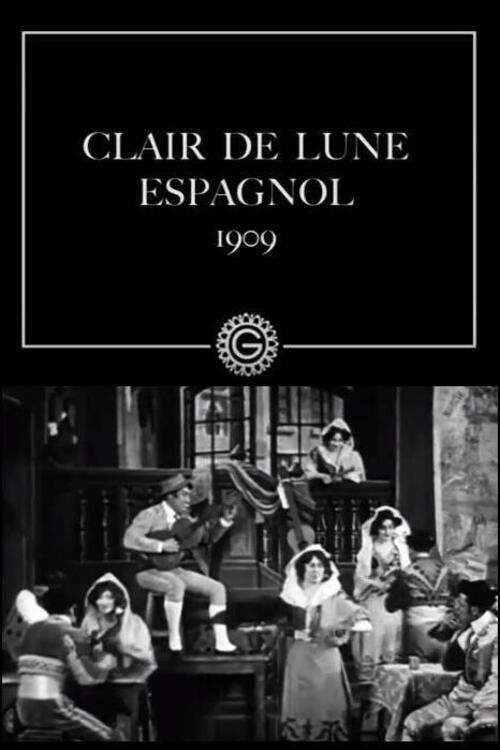

Spanish Clair de Lune

"A moonlit romance that reaches the heavens"

Plot

In this whimsical animated fantasy, two lovers passionately perform a traditional Spanish fandango dance in a moonlit setting. Their romantic moment is shattered when jealousy erupts between them, leading to a bitter quarrel that leaves the male lover heartbroken and desperate. In his despair, he decides to end his life by throwing himself from the window of his room, but fate intervenes in an extraordinary way. Instead of plummeting to his death, the anchor of a passing hot air balloon miraculously catches him, lifting him high into the night sky. The moon, personified and apparently amused by his predicament, begins to laugh at the unfortunate lover's plight, which only enrages him further. What follows is an epic battle between the desperate swain and the anthropomorphic moon, showcasing Émile Cohl's imaginative blend of romance, comedy, and surreal fantasy in one of animation's earliest narrative experiments.

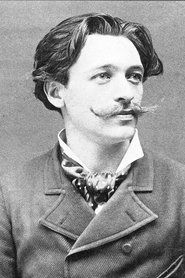

Director

About the Production

Created using cutout animation techniques on paper, with each frame drawn and photographed individually. Émile Cohl employed his innovative 'paper cinema' method, where characters and backgrounds were cut from paper and moved frame by frame. The film was likely produced in black and white, with some versions possibly hand-colored for special screenings. The animation process was extremely labor-intensive, requiring hundreds of individual drawings for the approximately 3-4 minute runtime.

Historical Background

1909 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring just over a decade after the invention of motion pictures. The film industry was transitioning from novelty to art form, with longer narratives and more sophisticated storytelling emerging. In France, Gaumont and Pathé were dominating global film production, with Paris serving as the world's cinema capital. This period saw the birth of animation as a distinct cinematic language, with pioneers like Émile Cohl, Winsor McCay, and J. Stuart Blackton experimenting with moving drawings. The year 1909 also witnessed significant technological advances in film equipment, including improved cameras and projection systems. Socially, Europe was experiencing the Belle Époque, a period of artistic innovation and cultural optimism, which influenced the whimsical and fantastical elements in films of this era. The public's fascination with new technologies like automobiles and airplanes is reflected in the film's balloon sequence.

Why This Film Matters

'Spanish Clair de Lune' represents a crucial milestone in the development of animation as an art form, showcasing early narrative techniques that would influence generations of animators. The film demonstrates Émile Cohl's innovative approach to storytelling through animation, blending romance, comedy, and fantasy in ways that were unprecedented for the time. Its personification of the moon and surreal imagery prefigure the surrealist movement that would emerge in art and cinema decades later. The film also reflects the international character of early cinema, combining Spanish cultural elements with French artistic sensibilities. As one of the earliest examples of character-driven animation, it helped establish the emotional and narrative possibilities of the medium. The film's survival makes it an invaluable document of early animation techniques and artistic vision, providing insight into how filmmakers of the era imagined the possibilities of moving images.

Making Of

Émile Cohl created 'Spanish Clair de Lune' during his most productive period at Gaumont, where he was the studio's primary animation director. The production involved meticulous frame-by-frame animation using paper cutouts, a technique Cohl pioneered. The moon character was likely animated using multiple paper drawings with slight variations to create the illusion of movement and expression. The film's surreal elements, particularly the battle between the lover and the moon, demonstrate Cohl's fascination with the impossible and his background in caricature and political satire. The production team was small, likely consisting of Cohl as the primary animator with assistance from a few technicians for the photography and development process. The film was shot on 35mm film using standard cameras of the era, with each frame carefully composed and photographed to create the illusion of movement.

Visual Style

The film employed basic stop-motion photography techniques using the standard 35mm film format of the era. Each frame was carefully composed and photographed to create smooth animation, a remarkable technical achievement for 1909. The cinematography likely featured simple camera setups with minimal movement, focusing attention on the animated elements. The visual style emphasized contrast and silhouette, particularly effective in the moonlit scenes. The film may have utilized multiple exposure techniques for certain effects, particularly in the supernatural sequences. The black and white photography would have enhanced the dreamlike quality of the moonlit setting, with careful attention to lighting and shadow to create atmospheric effects.

Innovations

The film represents significant technical innovation in early animation, particularly in its use of paper cutout animation techniques. Émile Cohl's method of creating movement through sequential paper drawings was groundbreaking for the time. The film's character animation, especially the personified moon, demonstrated sophisticated understanding of movement and expression. The seamless transitions between realistic and fantastical elements showcased advanced animation planning and execution. The film's survival after more than a century testifies to the durability of early film stock and preservation efforts. The balloon sequence required complex animation of both mechanical and organic movement, demonstrating Cohl's versatility as an animator.

Music

As a silent film, 'Spanish Clair de Lune' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition. The accompaniment likely featured Spanish-inspired music, possibly including fandango rhythms during the dance sequence. Theaters might have used popular songs of the era or classical pieces that matched the film's romantic and fantastical moods. The moonlit scenes would have been accompanied by more ethereal or mysterious musical selections. Large urban theaters with orchestras could have provided elaborate scores, while smaller venues might have used a single piano or organ. The title suggests Debussy's 'Clair de Lune' (composed 1890) could have been an appropriate musical choice, though it's uncertain if it was commonly used.

Famous Quotes

No documented dialogue - silent film with intertitles that have not survived in common records

Memorable Scenes

- The passionate fandango dance between the two lovers, showcasing early character animation and movement studies

- The dramatic suicide attempt from the window, captured with emotional intensity despite primitive animation techniques

- The miraculous balloon rescue sequence, demonstrating Cohl's imaginative approach to impossible situations

- The epic battle between the heartbroken lover and the laughing moon, a surreal and groundbreaking animated sequence that exemplifies early animation's creative possibilities

Did You Know?

- Émile Cohl is often called 'The Father of the Animated Cartoon' and this film is one of his earliest narrative works

- The film's title combines French ('Clair de Lune' meaning 'Moonlight') with Spanish themes, reflecting the international influences in early cinema

- This was created during the golden age of Gaumont's animation department, which Cohl helped establish

- The personified moon character was a recurring motif in Cohl's work, appearing in several of his films

- The film showcases Cohl's signature style of surreal transformations and impossible physics

- Only a few of Cohl's 1909 films survive today, making this a rare historical artifact

- The fandango dance sequence was likely based on popular Spanish dance performances that were fashionable in Paris at the time

- Cohl was in his early 50s when he created this film, having previously worked as a caricaturist and political cartoonist

- The balloon rescue sequence reflects the public fascination with aviation that followed the Wright brothers' 1903 flight

- The film was distributed internationally, with versions shown in both Europe and the United States

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception is difficult to document due to the limited film journalism of 1909, but trade publications like 'The Bioscope' and 'Moving Picture World' likely noted its technical innovation and whimsical charm. Modern film historians and animation scholars recognize the film as an important example of early narrative animation, praising Cohl's imaginative storytelling and technical experimentation. The film is frequently cited in academic works about the origins of animation and the development of surrealist cinema. Critics today appreciate the film's historical significance and its role in establishing animation as a medium capable of complex emotional storytelling.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th century audiences reportedly responded enthusiastically to Cohl's animated shorts, which were popular attractions in vaudeville theaters and early cinema houses. The film's blend of romance, comedy, and fantastic elements would have appealed to the diverse audiences of nickelodeons and music halls. The Spanish theme likely resonated with Parisian audiences' fascination with Spanish culture, which was fashionable during the Belle Époque. The surreal battle sequence would have been particularly impressive to viewers who had never seen such imaginative imagery in motion pictures. The film's short runtime and visual spectacle made it ideal for the varied programming of early cinema exhibitions.

Awards & Recognition

- None documented - film awards were not established in 1909

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès's fantasy films

- Early Spanish dance performances in Paris

- Traditional European folklore about the moon

- Contemporary fascination with aviation

- Parisian café culture and romantic literature

This Film Influenced

- Later works by Émile Cohl featuring personified celestial bodies

- Early Disney animations with similar romantic themes

- Surrealist films of the 1920s and 1930s

- Modern animated shorts featuring anthropomorphic nature elements

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved in archives, though complete versions may be rare. Some copies exist in film archives such as the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. The preservation status reflects the fragility of early nitrate film stock and the loss of many films from this era. Restoration efforts have likely been undertaken by film preservation institutions, though the quality may vary depending on the source material. The film's historical significance as an early work by Émile Cohl has contributed to its preservation priority.