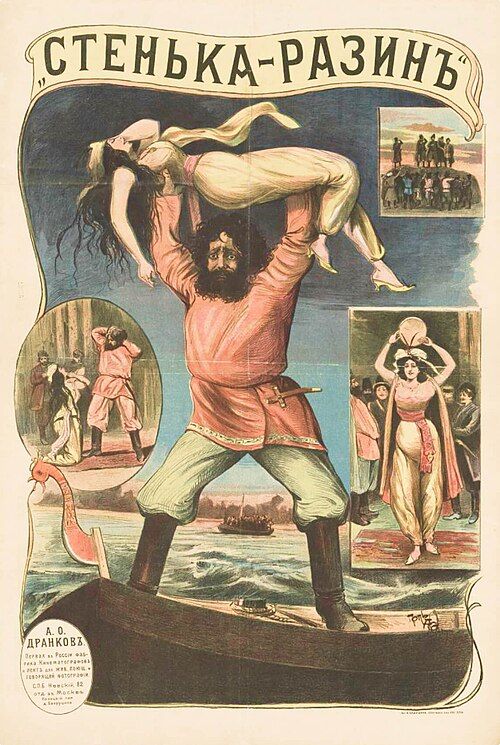

Stenka Razin

Plot

The 1908 Russian silent film 'Stenka Razin' follows the legendary 17th-century Cossack leader Stepan 'Stenka' Razin and his band of outlaws who live a life of freedom and revelry along the Volga River. After successfully raiding Persian territories, Razin captures a beautiful foreign princess and becomes completely infatuated with her, showering her with attention and gifts while neglecting his duties as leader. His loyal Cossack followers grow increasingly resentful and jealous of the princess, feeling that Razin has abandoned their cause and the brotherhood they shared. The discontented men devise a plan to turn Razin against his captive lover, suggesting that his devotion to this foreign woman has made him weak and unworthy of their loyalty. In the film's dramatic climax, Razin must choose between his love for the princess and his commitment to his men and their revolutionary cause, ultimately leading to a tragic sacrifice that demonstrates his unwavering dedication to the Cossack way of life.

Director

Vladimir RomashkovAbout the Production

This was one of the earliest narrative films produced in Russia, created during the pioneering days of Russian cinema. The film was shot on location near the Volga River to capture authentic settings. Due to the technical limitations of 1908, the entire production was filmed outdoors in natural light, as artificial lighting was not yet widely available. The film used simple camera techniques with mostly static shots, as camera movement was still in its infancy. The production faced significant challenges including the lack of established film infrastructure in Russia at the time.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1908, a pivotal year in Russian cinema when the industry was transitioning from simple actualities and exhibition films to narrative storytelling. This period saw the emergence of Russia's first film studios, most notably Alexander Drankov's company, which produced 'Stenka Razin.' The choice of Stenka Razin as a subject was particularly significant, as Razin was a folk hero who represented resistance against authority and oppression - themes that resonated deeply with Russian audiences during a period of growing social unrest leading up to the 1917 Revolution. The film emerged during the Silver Age of Russian culture, a period of extraordinary artistic achievement across literature, theater, and visual arts. The early Russian film industry was heavily influenced by French cinema, particularly the works of Georges Méliès and the Pathé company, but Russian filmmakers quickly began developing their own cinematic language and subject matter. The film's release came just three years after the 1905 Revolution, when political tensions remained high and stories of rebellion and social justice held particular relevance for Russian audiences.

Why This Film Matters

'Stenka Razin' holds immense cultural significance as one of the foundational texts of Russian cinema. It established several important precedents: it was among the first Russian films to adapt national folklore and historical subjects, setting a pattern for Russian cinema's engagement with national identity and history. The film's success demonstrated that Russian audiences would respond to films dealing with their own cultural heritage rather than just imported foreign content. It also helped establish the historical epic as a dominant genre in Russian cinema, a tradition that would continue through masterworks like Sergei Eisenstein's 'Alexander Nevsky' and 'Ivan the Terrible.' The character of Stenka Razin became an archetypal figure in Russian popular culture, representing the eternal struggle between freedom and authority, individual passion and collective duty. The film's portrayal of Cossack life contributed to the romanticization of Cossack culture in Russian consciousness. Its influence extended beyond cinema into literature, music, and visual arts throughout the 20th century.

Making Of

The making of 'Stenka Razin' represented a major breakthrough for the nascent Russian film industry. Director Vladimir Romashkov worked closely with producer Alexander Drankov, who had recently imported film equipment from France and established Russia's first film studio. The casting of Yevgeni Petrov-Krayevsky, a respected stage actor, was significant as it helped legitimize cinema as an art form among Russia's cultural elite. The production team faced numerous technical challenges, including the need to transport heavy camera equipment to remote locations along the Volga River. The film was shot during the summer months to take advantage of natural lighting, as artificial lighting technology was still primitive. The costumes and props were largely authentic, with many items borrowed from local museums or recreated based on historical descriptions. The filmmakers worked with local Cossack communities to ensure accurate portrayal of Cossack life and traditions. Post-production was minimal by modern standards, consisting mainly of assembling the shot sequences and adding intertitles to explain the narrative progression.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Stenka Razin' reflects the technical limitations and aesthetic conventions of 1908. The film was shot using hand-cranked cameras on celluloid film stock, resulting in the characteristic flickering motion of early cinema. The camera work is primarily static, with fixed wide shots that capture entire scenes in a single take, as camera movement was technically difficult and rarely used in this period. The filmmakers utilized natural lighting, shooting outdoors to take advantage of daylight, which created a certain authenticity in the outdoor scenes along the Volga River. The composition of shots follows theatrical conventions, with actors arranged in tableaux-like formations that recall stage productions. The film uses location shooting effectively, capturing the distinctive landscape of the Volga region to establish atmosphere and authenticity. Despite the technical limitations, the cinematography succeeds in creating a sense of scale and spectacle, particularly in scenes showing the Cossack camp and river settings.

Innovations

While 'Stenka Razin' may appear technically primitive by modern standards, it represented several important achievements for its time and place. The film demonstrated the feasibility of producing narrative fiction films in Russia, helping to establish a domestic film industry. Its use of location shooting along the Volga River was ambitious for 1908, requiring the transportation of heavy camera equipment to remote sites. The film's editing, though simple by contemporary standards, showed an understanding of narrative continuity and pacing. The production successfully coordinated multiple actors and extras in outdoor settings, a significant organizational challenge for early filmmakers. The film's costumes and props showed attention to historical detail, indicating a commitment to authenticity that was unusual for the period. Perhaps most significantly, the film proved that Russian cultural material could be successfully adapted to the new medium of cinema, encouraging further development of a distinctly Russian film language.

Music

As a silent film, 'Stenka Razin' had no recorded soundtrack, but it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibitions. In 1908, this typically meant a pianist or small ensemble playing appropriate music to accompany the action on screen. For a Russian historical drama like this, the musical accompaniment would likely have included Russian folk songs, particularly the famous 'Stenka Razin' ballad from which the film drew its story. Theaters might have also used popular classical pieces that matched the mood of different scenes - dramatic music for conflict, romantic themes for scenes with the princess, and triumphant music for the Cossack sequences. Some larger theaters employed small orchestras for film accompaniment, though this would have been rare for a short film of this type. The choice of live music significantly influenced the audience's emotional experience of the film, adding depth and cultural resonance to the visual narrative.

Famous Quotes

Better to drown in the Volga with honor than live with shame upon my head

A Cossack's heart belongs to freedom, not to a princess's golden cage

The river takes what it will, but the Cossack spirit cannot be drowned

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic climax where Stenka Razin throws the princess into the Volga River to prove his loyalty to his men, a scene that became iconic in Russian cinema and was referenced in numerous later works. The scene is shot from a distance, showing the small figure of the princess falling into the vast river while the Cossacks watch in solemn approval. This moment encapsulates the film's central conflict between personal desire and collective duty, and has been described by film historians as one of the most powerful sequences in early Russian cinema.

Did You Know?

- This is considered one of the first narrative fiction films produced in Russia, marking a significant milestone in Russian cinema history.

- The film is based on a popular Russian folk song about Stenka Razin, making it one of the earliest examples of literature adaptation in cinema.

- Yevgeni Petrov-Krayevsky, who played Stenka Razin, was a prominent stage actor from the Moscow Art Theatre, bringing theatrical prestige to this new medium.

- The film's director, Vladimir Romashkov, was one of Russia's first film directors and worked extensively with the Drankov Film Company.

- Stenka Razin was a real historical figure who led a major Cossack uprising against the Russian nobility in 1670-1671.

- The film was produced by Alexander Drankov, who is often called the 'father of Russian cinema' for his pioneering work in establishing the Russian film industry.

- Only fragments of this film are believed to survive today, as many early Russian films were lost during the 1917 Revolution and subsequent political upheavals.

- The film's story became a recurring theme in Russian culture, with multiple adaptations in various media throughout the 20th century.

- The production used actual Cossack performers as extras to add authenticity to the scenes depicting Cossack life.

- This film helped establish the historical epic as a popular genre in Russian cinema, a tradition that would continue through the Soviet era.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to 'Stenka Razin' was generally positive, with Russian newspapers and cultural journals praising the film as evidence that Russian cinema could compete with European productions. Critics particularly noted the film's ambitious scope and its successful adaptation of a beloved national legend. The performance of Yevgeni Petrov-Krayevsky received special commendation for bringing theatrical gravitas to the new medium of cinema. Modern film historians view 'Stenka Razin' as a crucial document in the development of Russian cinema, noting its pioneering role in establishing narrative film techniques in Russia. While the film's technical aspects appear primitive by contemporary standards, scholars recognize its importance in establishing a distinctly Russian cinematic tradition. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of early cinema as an example of how national cultures adapted the new medium of film to express their own stories and values.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enthusiastically received by Russian audiences upon its release in 1908, particularly among the growing urban middle class who frequented the new cinemas that were appearing in major cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg. Audiences were excited to see a familiar Russian legend brought to life on screen, and the film's dramatic story and exotic Cossack setting proved highly appealing. The film's success at the box office encouraged more Russian producers to invest in narrative films based on Russian subjects, accelerating the development of a national film industry. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences were particularly moved by the film's dramatic climax, which tapped into deep-seated cultural attitudes about honor, sacrifice, and loyalty. The film's popularity extended beyond major cities, as traveling exhibitors brought it to provincial towns where it often served as many viewers' first experience with narrative cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian folk ballads about Stenka Razin

- Historical chronicles of 17th-century Russia

- French narrative films of the early 1900s

- Stage melodramas popular in Russian theater

- Georges Méliès' narrative films

- Pathé company's production methods

This Film Influenced

- The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov (1909)

- The Defense of Sevastopol (1911)

- Stenka Razin (1939 Soviet remake)

- Andrei Rublev (1966)

- The Cossacks (1960)

- Russian folk film adaptations throughout the 20th century

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be partially lost, with only fragments surviving in various archives. Some scenes exist in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia, while other fragments are held by international film archives. The surviving material has been partially restored, but the complete film as originally released is no longer available. The loss is typical of films from this era, as early nitrate film stock was highly unstable and many early Russian films were destroyed during the political upheavals of the early 20th century.