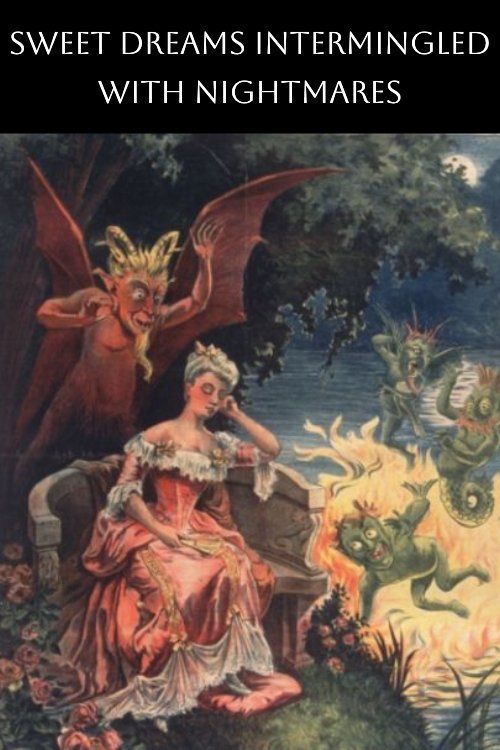

Sweet Dreams Intermingled With Nightmares

Plot

A woman peacefully dozes off on a park bench, only to be visited by the Devil who summons a mischievous imp to transport her to his sinister underground lair. The woman endures a series of nightmarish visions and torments in the imp's fantastical domain before abruptly awakening back on the park bench. Exhausted from her ordeal, she quickly falls back asleep, but this time a benevolent fairy appears to guide her through a beautiful and wondrous dreamland filled with magical delights. The film contrasts the terrifying visions of the Devil's realm with the serene beauty of the fairy's world, exploring the dual nature of dreams and nightmares.

Director

Cast

About the Production

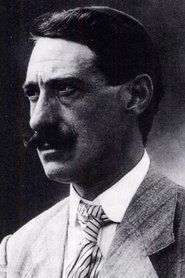

This film was created using multiple exposure techniques and early special effects methods including substitution splices and matte photography. Segundo de Chomón was renowned for his innovative visual effects work during this period, often collaborating with his wife Julienne Mathieu who starred in many of his films. The production utilized hand-tinted color techniques that were common in Pathé productions of this era.

Historical Background

In 1908, cinema was still establishing itself as a narrative art form, with most films lasting only a few minutes. This period saw the rise of trick films and fantasy movies, pioneered by Georges Méliès and followed by filmmakers like Segundo de Chomón. The film industry was dominated by French companies, particularly Pathé Frères, which was expanding globally. Cinema was transitioning from simple actualities and novelty films to more complex storytelling. The psychological themes of dreams and nightmares in this film reflect the growing interest in Freudian psychology that would soon influence artistic works across various media.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of early fantasy cinema and the development of visual effects in film. It demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of cinematic language that was developing even in these early years, particularly in its use of dream sequences to explore psychological themes. The film's dual structure contrasting nightmares with pleasant dreams anticipated the complex narrative techniques that would become standard in later cinema. As part of the body of work by Segundo de Chomón, it contributed to the evolution of special effects and fantasy filmmaking that would influence later directors including those working in the horror and fantasy genres.

Making Of

The production of this film required careful planning of special effects sequences, particularly the transformation scenes and the appearance of supernatural beings. Segundo de Chomón was known to work extensively with his wife Julienne Mathieu to choreograph these sequences, often requiring multiple takes to achieve the desired visual effects. The filming likely took place in Pathé's studio in Paris, where de Chomón had access to sophisticated equipment for the time. The hand-coloring process would have been completed after filming by teams of women workers who meticulously applied color to each frame. The film's fantasy elements required elaborate props and set pieces that could be manipulated for the trick photography effects.

Visual Style

The cinematography employed multiple exposure techniques to create the supernatural appearances of the Devil and fairy. Substitution splices were used for transformation effects, while careful matte photography created the illusion of characters appearing and disappearing. The film utilized the fixed camera perspective typical of the era, with movement created through the action within the frame. The hand-coloring process added visual appeal and helped distinguish between the nightmare and dream sequences, likely using darker tones for the Devil's realm and brighter colors for the fairy's domain.

Innovations

This film showcased several technical innovations for its time, including sophisticated multiple exposure techniques that allowed supernatural beings to appear and interact with the physical world. The substitution splices used for transformation effects were particularly advanced for 1908. The hand-coloring process, while labor-intensive, created a visually striking result that enhanced the fantasy elements. The film also demonstrated advanced understanding of continuity and narrative structure within the constraints of early cinema technology.

Music

As a silent film from 1908, it would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition. The specific musical score is not documented, but typical accompaniment for such fantasy films would include piano or organ music that could shift between dramatic and whimsical tones to match the on-screen action. Some theaters might have used compiled classical pieces or improvisation by the house musician. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial in establishing the mood shifts between the nightmare and dream sequences.

Memorable Scenes

- The appearance of the Devil summoning the imp with magical gestures, the transformation sequence where the woman is transported to the underworld, the contrast between the dark, terrifying nightmare realm and the bright, beautiful fairy dreamland, the final awakening sequence that blurs the line between dream and reality

Did You Know?

- This film is also known by its French title 'Le cauchemar de Fantoche' in some references, though this may be a confusion with another similar film.

- Segundo de Chomón was often called 'the Spanish Méliès' due to his similar style of fantasy films and special effects innovations.

- The film was part of the golden age of trick films that flourished between 1900-1910, when audiences were fascinated by cinematic magic.

- Julienne Mathieu, who plays the woman, was married to Segundo de Chomón and appeared in over 100 of his films.

- The dual dream structure (nightmare followed by pleasant dream) was a relatively sophisticated narrative technique for 1908.

- The film was hand-colored frame by frame, a laborious process that added significant production time and cost.

- Pathé Frères, the production company, was one of the largest film studios in the world during this period.

- The imp character was likely played by a child actor or a small adult, a common practice in early fantasy films.

- The film's special effects were created in-camera, as post-production editing techniques were still in their infancy.

- This film represents one of the earliest examples of the 'dream sequence' trope that would become common in cinema.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of this specific film are scarce, as film criticism was still in its infancy in 1908. However, trick films and fantasies by de Chomón were generally well-received by audiences and appreciated for their technical innovations. Modern film historians recognize this work as an important example of early special effects cinema and a significant contribution to the fantasy genre's development. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early cinema and the evolution of visual effects techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1908 were fascinated by trick films and magical cinema, and de Chomón's works were popular attractions. The combination of supernatural elements, visual effects, and the novelty of hand-colored film would have made this an engaging spectacle for early cinema-goers. The dream narrative, while simple, offered viewers a fantastical escape that was highly valued in the early cinema experience. Modern audiences viewing this film in film festivals or archives often express appreciation for its historical significance and technical achievements within the constraints of early filmmaking.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works of Georges Méliès

- Literary traditions of dream narratives

- Gothic literature

- Fairy tale traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later dream sequence films

- Fantasy and horror cinema

- Surrealist films of the 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various film archives, including the Cinémathèque Française. Some versions exist with the original hand-coloring intact, while others survive only in black and white. The film has been restored and digitized by several film preservation organizations and is available through specialized film archives and some streaming platforms dedicated to early cinema.