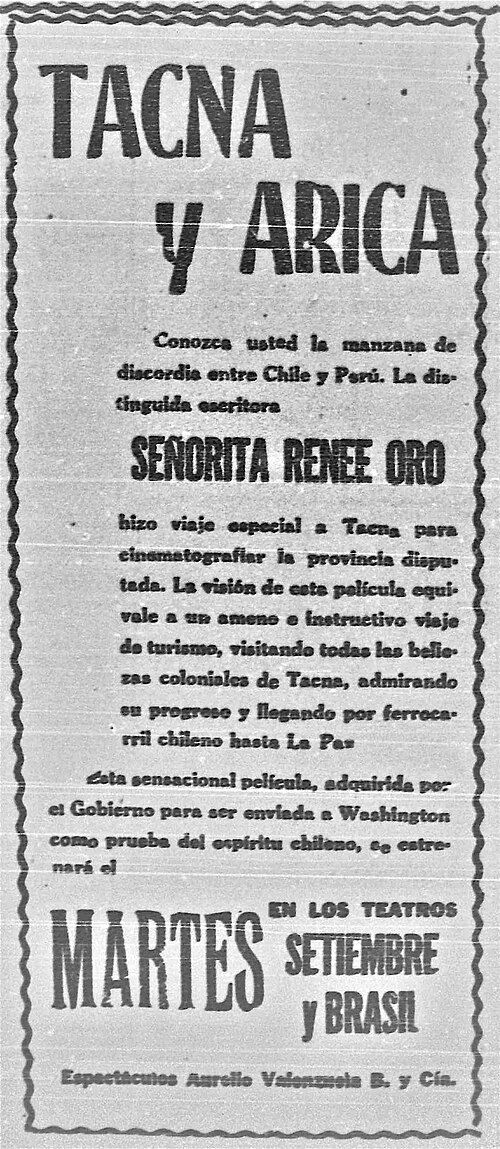

Tacna y Arica

Plot

This 1924 silent documentary presents a propagandistic view of the disputed Peruvian provinces of Tacna and Arica, which were under Chilean administration following the War of the Pacific. The film showcases the economic prosperity, infrastructure development, and cultural vitality of these regions under Chilean influence and investment. Through carefully composed images of bustling markets, modern facilities, agricultural productivity, and thriving communities, the documentary argues for the benefits of Chilean governance. The narrative emphasizes progress, stability, and economic growth while subtly promoting the Chilean position in the ongoing territorial dispute with Peru.

Director

About the Production

This film was created during a critical period in the Tacna-Arica dispute, just five years before the territories would be formally divided between Peru and Chile. The production likely faced significant logistical challenges filming in disputed territories with heightened political tensions. As a propaganda piece, it would have required careful coordination with local Chilean authorities and likely employed selective framing techniques to emphasize prosperity and progress under Chilean administration.

Historical Background

The film was created during a critical phase of the Tacna-Arica dispute, a territorial conflict that began after Chile's victory in the War of the Pacific (1879-1884). The Treaty of Ancón (1883) granted Chile administration over these provinces with the stipulation that a plebiscite would determine their final sovereignty. However, the plebiscite was repeatedly delayed due to disagreements over voter eligibility and other issues. By 1924, when this film was made, the territories had been under Chilean control for over 40 years, leading to significant demographic and cultural changes. The period saw intense propaganda efforts from both sides as international mediation efforts intensified. The dispute would finally be resolved by the Treaty of Lima in 1929, with Tacna returning to Peru and Arica remaining with Chile, but with Peru guaranteed certain commercial rights and port access.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important early example of cinema being used as a tool for political propaganda and international diplomacy in South America. It demonstrates how emerging film technology was harnessed to shape public opinion and influence territorial disputes. The documentary also stands as a rare example of early Chilean documentary filmmaking and one of the earliest known works by a female director in Chilean cinema. The film provides historical insight into how the Chilean state and its supporters sought to portray their administration of the disputed territories as beneficial and progressive. Its existence, even in documentation alone, illustrates the growing importance of visual media in political communication during the early 20th century.

Making Of

The production of 'Tacna y Arica' took place during a period of intense diplomatic negotiations and heightened nationalist sentiments between Peru and Chile. Filming in these disputed territories would have required careful navigation of local sensitivities and political tensions. The director, Renée Oro, was working in an era when female directors were extremely rare, particularly in Latin America. The film was likely commissioned by Chilean interests seeking to strengthen their position in the ongoing territorial dispute. The production team would have had to work with local Chilean authorities to access locations and ensure favorable portrayals of life under Chilean administration. The documentary employs techniques common to propaganda films of the era, including selective framing, staged scenes of prosperity, and emphasis on modern infrastructure and economic development.

Visual Style

As a silent documentary from 1924, the film would have employed black and white cinematography typical of the era. The visual style likely emphasized grand vistas of landscapes, modern infrastructure, bustling markets, and prosperous communities to support its propagandistic message. The cinematography probably used techniques such as panoramic shots to showcase the scale of development, close-ups to highlight prosperity, and carefully composed scenes to present an idealized view of life under Chilean administration. The camera work would have been static or minimally mobile, reflecting the technical limitations of the period.

Innovations

The film represents an early example of documentary filmmaking in Chile and demonstrates the technical capabilities of South American cinema in the 1920s. While specific technical innovations are not documented, the production would have required portable camera equipment capable of on-location shooting in the challenging terrain of the Andes region. The film's existence indicates that Chile had developed sufficient technical expertise and infrastructure to produce documentary films for political purposes by the mid-1920s.

Music

As a silent film, 'Tacna y Arica' would have been accompanied by live musical performances during theatrical screenings. The musical selections would likely have been patriotic or uplifting in nature, possibly including Chilean national music or classical pieces that emphasized progress and prosperity. The score would have been designed to enhance the film's propagandistic message and emotional impact on audiences.

Famous Quotes

No documented quotes survive from this lost film

Memorable Scenes

- Specific scenes are not documented due to the film's lost status, but likely included footage of Tacna and Arica's markets, infrastructure, and daily life under Chilean administration

Did You Know?

- The film was made during the final years of the Tacna-Arica dispute, which had been ongoing since the War of the Pacific (1879-1884)

- Director Renée Oro is one of the earliest known female directors in Chilean cinema history

- The territories depicted would be formally divided in 1929, with Tacna returning to Peru and Arica remaining with Chile

- This film represents an early example of using cinema as a tool for international political propaganda in South America

- The film is now considered lost, like approximately 90% of silent films produced worldwide

- The documentary was likely screened in Chile and possibly internationally to influence opinion about the territorial dispute

- The timing of the film's release (1924) coincided with renewed diplomatic efforts to resolve the Tacna-Arica question

- Very little documentation survives about Renée Oro's career beyond this film

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Tacna y Arica' is difficult to ascertain due to the film's lost status and limited documentation. However, as a propaganda piece, it likely received favorable coverage in Chilean media while being viewed with suspicion in Peru. The film would have been evaluated primarily for its political effectiveness rather than its artistic merits. Modern film historians consider it primarily as a historical artifact documenting both the territorial dispute and early Chilean cinema development.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1924 would have been divided along national lines. Chilean audiences likely received the film positively as it reinforced their country's position in the territorial dispute and showcased Chilean development in the regions. Peruvian audiences, if they had access to it, would probably have viewed it skeptically or with hostility due to its propagandistic nature and Chilean perspective. The film was likely screened primarily in Chile and possibly at international venues where Chile sought to present its case regarding the disputed territories.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Contemporary propaganda documentaries

- Early Soviet documentary techniques

- Government-sponsored films of the era

This Film Influenced

- Later Chilean propaganda documentaries

- Subsequent films about the Tacna-Arica dispute

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered lost. Like approximately 90% of silent films worldwide, no known copies of 'Tacna y Arica' (1924) survive. Only documentation of its existence and purpose remains in historical records and film archives.