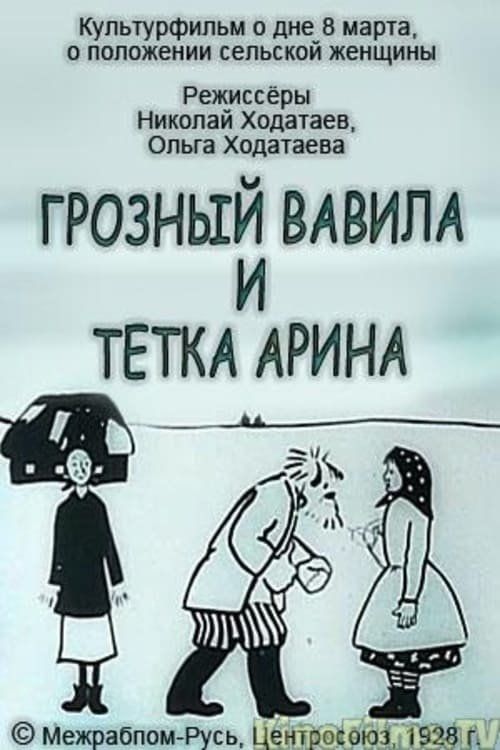

Terrible Vavila and Auntie Arina

Plot

This educational Soviet animated film tells the story of Terrible Vavila, a patriarchal figure representing the old oppressive ways, and Auntie Arina, a rural woman who represents the struggles and eventual liberation of peasant women. The narrative follows Arina's journey from a life of subjugation and hard labor under Vavila's tyranny to her awakening and empowerment through the ideals of International Women's Day (March 8th). Through symbolic imagery and allegorical storytelling, the film depicts how Soviet ideology and the women's movement transform rural women's lives, freeing them from traditional oppression. The animation uses folk-inspired characters to illustrate the contrast between pre-revolutionary backwardness and Soviet progress, showing how education and collective action enable women like Arina to claim their rights and dignity.

Director

About the Production

Created during the pioneering era of Soviet animation, this film was produced using cut-out animation techniques, which were common in early Soviet animation due to limited resources and technical constraints. Olga Khodatayeva, one of the first women animators in the Soviet Union, led a small team of artists who hand-drew and cut each figure. The film was part of a series of educational animations produced to promote Soviet ideological values and social reforms. The production faced significant material shortages, a common issue in the late 1920s Soviet film industry, requiring creative solutions for animation materials.

Historical Background

This film was created during a crucial period of Soviet social transformation in 1928, when Joseph Stalin was consolidating power and launching the First Five-Year Plan. The late 1920s saw intense efforts to modernize the Soviet Union and transform traditional social structures. International Women's Day, though celebrated in Russia since 1913, was being heavily promoted by the Soviet state as a tool for advancing gender equality and women's participation in the workforce. The film emerged during the early Soviet animation boom, when the state recognized animation's potential for propaganda and education. Rural women were particularly targeted by Soviet campaigns as they were seen as crucial to the success of collectivization and industrialization. The film reflects the Soviet Union's ambitious social engineering projects and the belief that cinema could accelerate social change by reaching illiterate populations through visual storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a significant milestone in both Soviet animation history and women's cinema. As one of the earliest animated films directed by a woman, it challenges the male-dominated narrative of early animation history. The film's focus on rural women's liberation reflects the Soviet Union's unprecedented legal advances in women's rights, including divorce rights, abortion access, and workplace equality. It demonstrates how animation was used as a tool for social education and political mobilization in the early Soviet period. The film's blend of folk tradition and revolutionary ideology exemplifies the Soviet approach to cultural transformation - using familiar forms to introduce radical ideas. Its existence proves that women played crucial roles in early Soviet animation, a fact often overlooked in film history. The film also represents an early example of animation being used for feminist messaging, predating similar efforts in Western cinema by decades.

Making Of

Olga Khodatayeva worked with a small team of female artists in a cramped Moscow studio to create this film. The animation process was entirely manual, with each frame hand-drawn on paper, cut out, and photographed one by one. Khodatayeva, who had previously worked as an illustrator for children's books, brought her understanding of visual storytelling to animation. The team worked under tight deadlines to complete the film for March 8th celebrations. During production, they faced significant challenges including material shortages - they had to reuse paper and make their own animation stands. The film's folk-inspired visual style was deliberately chosen to make the revolutionary message more accessible to rural audiences, many of whom were illiterate. Khodatayeva and her team consulted with women's organizations to ensure the film accurately reflected the real struggles of rural women.

Visual Style

The film employed cut-out animation techniques, which were characteristic of early Soviet animation due to economic constraints. The visual style drew heavily from Russian folk art, particularly lubok prints and traditional peasant art forms. The animation used bold, contrasting colors to emphasize the moral and political divisions between characters. The cinematography featured static camera angles typical of early animation, with careful composition to maximize visual impact. The filmmakers used exaggerated character designs to clearly communicate the ideological positions of each figure - Vavila was depicted with harsh, angular features while Arina had softer, more sympathetic characteristics. The animation incorporated constructivist influences in its geometric backgrounds and symbolic use of color, particularly red to represent revolutionary ideals.

Innovations

While technically simple by modern standards, the film represented several achievements for its time and context. It demonstrated how cut-out animation could be used effectively for propaganda and education with minimal resources. The filmmakers developed innovative techniques for creating movement and emotion using limited materials. The film's use of folk art aesthetics in animation was pioneering, showing how traditional visual styles could be adapted for modern messaging. The production team created efficient workflows that allowed them to produce the film quickly for the March 8th deadline. The film also demonstrated early experiments in using animation for social education rather than entertainment, influencing subsequent Soviet educational films. Despite material shortages and technical limitations, the team achieved visual clarity and narrative coherence that made the film effective with its target audience.

Music

The original film was silent, as was standard for Soviet cinema in 1928. During theatrical screenings, the film was accompanied by live music, typically performed by a pianist or small orchestra using popular revolutionary songs and folk melodies. The musical accompaniment varied by venue, with larger theaters providing more elaborate scores while rural screenings often featured just a single accordion or balalaika. Some screenings included live narration, with local activists or party members explaining the film's message. The absence of synchronized sound meant that intertitles were used to convey key plot points and ideological messages. The musical choices were deliberately made to bridge traditional folk culture with revolutionary themes, helping audiences connect with the film's message.

Famous Quotes

No documented quotes - as a silent film, communication was primarily visual through intertitles and animation

Memorable Scenes

- The transformation scene where Auntie Arina sheds her traditional garments and adopts modern Soviet dress, symbolizing her liberation from patriarchal oppression. This sequence used innovative animation techniques to show the gradual change, with each frame carefully crafted to emphasize the ideological significance of this metamorphosis. The scene was accompanied by symbolic imagery of chains breaking and flowers blooming, representing freedom and new beginnings.

Did You Know?

- This film was specifically created to be screened on International Women's Day (March 8th) across Soviet cinemas and educational institutions

- Olga Khodatayeva was one of only three women animators working in the Soviet Union during the 1920s

- The film's title characters are based on traditional Russian folk tale archetypes, repurposed for Soviet propaganda

- It was among the first Soviet animations to explicitly address women's rights and gender equality

- The film was distributed not only in cinemas but also shown at collective farms, workers' clubs, and women's meetings

- Despite its educational purpose, the film incorporated avant-garde artistic techniques influenced by constructivism

- The animation was created without synchronized sound, as sound technology was not yet available in Soviet cinema

- Only fragments of the original film are known to survive, with some scenes preserved in the Russian State Film Archive

- The character of Auntie Arina was voiced (in live screenings) by different local women activists at each showing

- The film was part of a larger Soviet campaign to increase female participation in the workforce and collectivization

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its clear ideological message and accessible presentation. Pravda and other official newspapers highlighted it as an example of how cinema could serve educational and revolutionary purposes. Critics noted how effectively the film used folk art traditions to communicate modern socialist values. However, some reviewers felt the animation was technically primitive compared to Western standards. In modern retrospectives, film historians recognize the film as an important artifact of early Soviet animation and women's cinema, though they note its heavy-handed propaganda approach. Animation scholars particularly value it as an example of Olga Khodatayeva's pioneering work and the role of women in early Soviet animation. The film is now studied more for its historical significance than its artistic merits.

What Audiences Thought

The film was primarily shown to organized audiences of workers and peasants rather than general cinema-goers. Reports from women's organizations and collective farms indicate that rural women found the story relatable and inspiring, though some viewers struggled with the abstract symbolism. The character of Auntie Arina resonated strongly with female audiences who saw their own struggles reflected in her journey. The film generated discussions at women's meetings and was used as an educational tool in literacy campaigns. However, some traditional rural viewers found the revolutionary message challenging to accept. Children particularly enjoyed the folk-tale elements and animation style. The film's reception varied by region - it was more enthusiastically received in areas where collectivization was already underway compared to more traditional regions.

Awards & Recognition

- No documented awards - educational films of this period typically were not part of award circuits

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian folk tales

- Lubok prints

- Constructivist art

- Soviet propaganda posters

- Traditional peasant art

- Revolutionary literature

- Agitprop theater

This Film Influenced

- Other Soviet educational animations of the 1930s

- Later Soviet films about rural women

- Propaganda animations in other socialist countries

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - only fragments of the original film survive in the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond). Some scenes are missing or badly damaged. The film exists as an incomplete nitrate print with significant deterioration. Restoration efforts have been limited due to the fragmentary nature of surviving materials. What remains provides valuable insight into early Soviet animation and Olga Khodatayeva's work, but the complete narrative cannot be fully reconstructed from available elements.