The Artist's Dreams

"Where Art Comes to Life and Appetites Run Wild!"

Plot

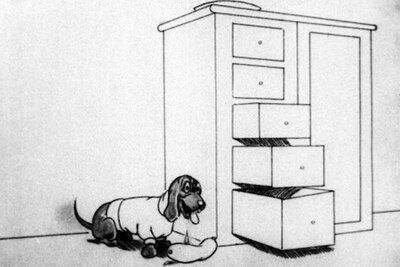

In this pioneering 1913 animated short, an artist creates a drawing of a dachshund that miraculously comes to life. The animated dog proceeds to interact with his creator in increasingly mischievous ways, culminating in the dog eating the sausages that the artist has drawn on paper. The film showcases the boundary-breaking technique of combining live-action footage with animated characters, as the real-world artist and his animated creation share the screen. The clever narrative demonstrates early animation's potential for storytelling and visual gags, establishing a template for future animated shorts that would blend reality and imagination.

Director

About the Production

This film was created using paper cut-out animation techniques combined with live-action photography. Bray developed a method of photographing animated drawings frame by frame, then combining them with live-action footage through double exposure. The production involved meticulous planning to synchronize the artist's movements with the animated character's actions. The dachshund character was animated using articulated paper joints to create smooth movement. This was one of the first films to successfully integrate animation with live-action in a narrative context.

Historical Background

1913 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring during the transition from short novelty films to more sophisticated narrative cinema. The film industry was rapidly consolidating, with major studios like Paramount and Universal being formed. Animation was in its absolute infancy, with most animated films being simple tricks or brief novelties. Winsor McCay had just released 'Gertie the Dinosaur' earlier in 1913, establishing that animation could create characters with personality. Bray's work represented a different approach - focusing on technical innovation and production efficiency rather than artistic expression. The film was made during the Progressive Era in America, a time of technological optimism and belief in scientific progress, which influenced the experimental nature of early animation. Cinema was still largely silent, with live musical accompaniment provided in theaters, and films were typically shown in vaudeville programs rather than dedicated cinemas.

Why This Film Matters

'The Artist's Dreams' holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest examples of mixed-media animation, establishing techniques that would become standard in the industry for decades. The film demonstrated that animation could interact with the real world, opening up creative possibilities that would later be explored in everything from Disney's 'Alice Comedies' to modern films like 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit.' Bray's innovations in production methods helped establish animation as a viable commercial medium rather than just a novelty act. The film's success contributed to the development of the animation industry in America, paving the way for the establishment of dedicated animation studios. It also represents an early example of meta-cinema, with a film about an artist creating art that comes to life - a theme that would recur throughout animation history. The technical achievements in this film influenced generations of animators and helped establish many of the fundamental principles of animation production.

Making Of

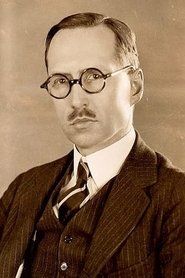

The production of 'The Artist's Dreams' represented a significant technical challenge for 1913. John Randolph Bray had to develop new techniques to seamlessly blend live-action footage with animated elements. He created a special camera rig that allowed for precise registration between the live-action and animation plates. The dachshund character was constructed from multiple layers of paper with joints connected by tiny pins, allowing for articulate movement. Each frame required careful manipulation of the paper character, photographing it, then rewinding the film and shooting the live-action elements. Bray's wife Margaret assisted with the painstaking animation process, moving the paper characters between exposures. The film was shot in Bray's home studio in the Bronx, where he had converted a room into a makeshift animation studio with custom-built equipment. The production took several weeks to complete, which was unusually long for films of this era but necessary for the complex technical requirements.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Artist's Dreams' was groundbreaking for its time, utilizing innovative techniques to combine live-action and animation. Bray employed a dual-exposure method that required precise camera registration to ensure the animated elements aligned correctly with the live-action footage. The film used stop-motion photography for the animated sequences, with each frame carefully composed to maintain consistency. The lighting had to be carefully controlled to ensure the animated paper cut-outs appeared natural within the live-action environment. The camera work was relatively static by modern standards, typical of early cinema, but the technical challenge of synchronizing the different elements required considerable skill. The film's visual style was clean and simple, with clear outlines that helped the animated characters stand out against the live-action background. The cinematography prioritized clarity and technical precision over artistic flourishes, reflecting Bray's focus on innovation and production efficiency.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was the successful integration of live-action footage with animated elements, a groundbreaking accomplishment for 1913. Bray developed a registration system that allowed for precise alignment between the different media, creating the illusion that the animated dachshund existed in the same space as the live-action actor. The animation technique used articulated paper cut-outs with joints connected by pins, allowing for more fluid movement than earlier methods. Bray also experimented with timing and spacing in animation, creating more naturalistic motion than many contemporaneous works. The film demonstrated early use of what would later be called 'special effects photography,' with careful control of exposure and lighting to blend the different elements seamlessly. These innovations were so significant that Bray would later patent several of the techniques first demonstrated in this film. The production process also established workflows that would become standard in animation studios, including the separation of different animation elements onto different layers.

Music

As a silent film from 1913, 'The Artist's Dreams' had no synchronized soundtrack. The musical accompaniment would have been provided live in theaters, typically by a pianist or small orchestra. The music would have been selected from standard theater libraries of the time, with lively, comedic pieces chosen to match the film's whimsical tone. The tempo would have been coordinated with the on-screen action, particularly during the animated sequences where musical cues would emphasize the dachshund's movements and the sausage-eating gag. Some larger theaters might have had special music composed for the film, but this would have been rare for a short animated piece. The absence of dialogue meant that visual storytelling and physical comedy had to carry the entire narrative, making the visual elements particularly important. Modern screenings of the film typically use period-appropriate piano accompaniment to recreate the original viewing experience.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue exists as this is a silent film; the story is told entirely through visual action and intertitles if any were used

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic scene where the animated dachshund stretches from the drawn paper into three-dimensional space to eat the sausages, demonstrating the seamless integration of animation and live-action that was revolutionary for 1913

Did You Know?

- This was one of John Randolph Bray's earliest experiments combining live-action with animation, predating his more famous works like 'Colonel Heeza Liar'

- The dachshund character was reportedly inspired by Bray's own pet dog

- The film was distributed by Pathé Exchange, one of the major film companies of the early silent era

- Bray patented several animation techniques that were first demonstrated in this film

- The sausage-eating gag became a recurring theme in early animation, appearing in several subsequent Bray productions

- This film was created before the establishment of major animation studios, making it part of animation's true pioneering era

- The production used a modified camera setup that Bray designed himself to achieve the live-action/animation combination

- Margaret Bray, John's wife, not only appeared in the film but also assisted with the animation process

- The film's success helped Bray secure funding to establish his own animation studio

- Only a few prints of this film are known to exist, making it extremely rare among early animation works

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception in 1913 was generally positive, with trade publications like 'The Moving Picture World' praising the film's technical innovation and clever concept. Critics noted the seamless integration of animation and live-action as particularly impressive for the time. The film was often described as 'amusing' and 'ingenious' in reviews of the period. Modern film historians recognize 'The Artist's Dreams' as a significant milestone in animation history, though it is less well-known than some contemporaneous works like McCay's 'Gertie the Dinosaur.' Animation scholars particularly value the film for its demonstration of early mixed-media techniques and its role in establishing John Randolph Bray as a pioneering figure in American animation. The film is frequently cited in academic works about early animation history as an example of the technical experimentation occurring in the field during this period.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1913 reportedly responded with enthusiasm and amazement to the film's technical achievements. The sight of an animated character interacting with a real person was considered magical and revolutionary by moviegoers of the era. The film was popular enough to warrant wider distribution through Pathé Exchange, indicating strong audience demand. The humorous premise of a dog eating drawn sausages appealed to both children and adults, making it suitable for the mixed audiences typical of early cinema. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences particularly enjoyed the film's clever gags and the novelty of seeing animation combined with live-action. The film's success helped establish a market for animated shorts that would grow throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Modern audiences who have had the opportunity to see the film (primarily through film festival screenings and archive presentations) often express surprise at the sophistication of the techniques used in 1913.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Winsor McCay's early animation experiments

- Émile Cohl's Fantasmagorie (1908)

- J. Stuart Blackton's Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906)

- Georges Méliès's trick films

- Contemporary comic strips and cartoons

This Film Influenced

- Bray's later Colonel Heeza Liar series

- The Fleischer Brothers' Out of the Inkwell series

- Disney's Alice Comedies

- Later mixed-media animation experiments

- Modern live-action/animation hybrid films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some degradation common to nitrate films of this era. A few prints exist in film archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art's film collection. The surviving prints show signs of wear but are viewable. Restoration efforts have been limited due to the film's age and rarity, though digital preservation has been undertaken by some archives.