The Battle of the Somme

"The Greatest Picture in the World - The Real Thing"

Plot

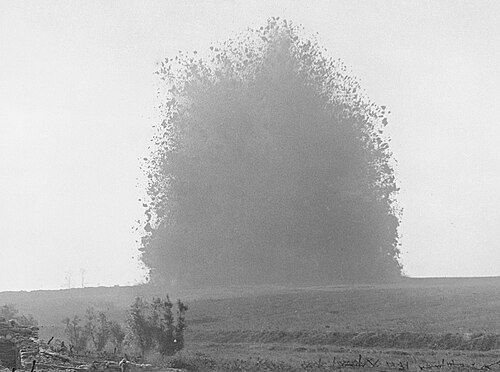

The Battle of the Somme is a groundbreaking documentary that captures the British Army's preparations and initial engagement in one of World War I's most devastating battles. The film opens with soldiers in training camps, moving supplies and artillery to the front lines, and preparing trenches for the massive offensive. It then transitions to the actual battle beginning on July 1, 1916, showing troops going 'over the top' from their trenches and advancing across no man's land under enemy fire. The documentary includes footage of artillery bombardments, soldiers carrying wounded comrades, and scenes of captured German prisoners. The film concludes with sequences showing the aftermath of battle, medical stations treating the wounded, and soldiers resting in captured enemy trenches, presenting both the military operations and human cost of this pivotal engagement.

Director

John McDowellAbout the Production

Filmed under extremely dangerous conditions with cinematographers Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell risking their lives to capture authentic battle footage. The film was shot over a period of several weeks, with cameras sometimes positioned just yards from enemy lines. Many scenes had to be staged or re-enacted after the fact when actual combat footage proved impossible to capture safely. The production faced numerous technical challenges including the bulkiness of cameras, the need for hand-cranking during filming, and the constant threat of artillery fire.

Historical Background

The Battle of the Somme was filmed and released during one of the darkest periods of World War I, when the British public was growing increasingly war-weary after two years of conflict. The Battle of the Somme itself, which began on July 1, 1916, resulted in nearly 60,000 British casualties on its first day alone - the bloodiest single day in British military history. The film was commissioned as part of a government effort to maintain public support for the war and counter anti-war sentiment that was beginning to emerge. 1916 was also a year of significant technological advancement in cinema, with longer films becoming more common and movie theaters established as important social institutions. The film's release came just months before the introduction of conscription in Britain, making it a crucial tool for maintaining public morale and support for the war effort.

Why This Film Matters

The Battle of the Somme revolutionized both documentary filmmaking and the relationship between cinema and society. It was the first time most British civilians had seen realistic images of warfare, shattering the romanticized notions of combat that had dominated popular culture. The film created a new visual language for representing war on screen, influencing countless documentaries and feature films that followed. It demonstrated cinema's power as a tool for propaganda and social manipulation, setting precedents for how governments would use film to shape public opinion during future conflicts. The film also changed the public's relationship with the war, making the distant conflict feel immediate and personal for millions of viewers. Its success established the documentary as a legitimate and powerful film genre, paving the way for future non-fiction filmmaking. The film's impact extended beyond Britain, influencing how other nations would use cinema for wartime propaganda throughout the 20th century.

Making Of

The production of The Battle of the Somme was a remarkable feat of wartime filmmaking. Cinematographers Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell were given official permission to film at the front, becoming some of the first cameramen to capture actual combat on film. They worked with cumbersome hand-cranked cameras that weighed over 20 pounds and had to be manually operated even while under fire. The filmmakers had to negotiate strict military censorship, with the War Office requiring approval of all footage before release. Many of the most dramatic scenes, including the famous 'over the top' sequence, were actually staged behind the lines with soldiers re-enacting combat movements for the camera. The film was edited in London under tight security, with officials carefully selecting footage that would boost morale while not revealing too much strategic information. The production team worked around the clock to complete the film while the battle was still ongoing, creating a sense of immediacy that contributed to its powerful impact on audiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Battle of the Somme was groundbreaking for its time, representing some of the earliest combat footage ever captured. Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell used hand-cranked cameras that required constant manual operation, making steady shots extremely difficult under combat conditions. The filmmakers worked with natural light, resulting in images that vary dramatically in quality depending on weather conditions and time of day. The camera work includes long shots of troop movements, medium shots of soldiers in trenches, and rare close-ups of individual faces, creating a surprisingly intimate connection with the subjects. The cinematographers employed innovative techniques such as mounting cameras on tripods in trenches and using wide-angle lenses to capture the scale of the battlefield. Despite technical limitations, the footage achieves remarkable clarity and composition, with many shots demonstrating sophisticated understanding of visual storytelling. The black and white imagery creates a stark, documentary aesthetic that enhances the film's sense of authenticity and immediacy.

Innovations

The Battle of the Somme achieved several technical breakthroughs in documentary filmmaking. It was the first feature-length documentary to capture authentic combat footage, pushing the boundaries of what was considered possible to film under dangerous conditions. The cinematographers developed new techniques for stabilizing cameras in trenches and protecting equipment from mud and weather. The film pioneered the use of multiple camera units to cover different aspects of a single event, creating a more comprehensive visual record. The editing techniques employed, including the juxtaposition of preparation, action, and aftermath sequences, established new conventions for documentary storytelling. The production demonstrated that documentary films could achieve commercial success on par with feature fiction films, helping to establish documentary as a viable commercial genre. The film's distribution network, which reached thousands of theaters across Britain and several other countries, set new standards for documentary film distribution and exhibition.

Music

The original film was silent, as was standard for 1916 productions, but was typically screened with live musical accompaniment. The British government commissioned a special musical score to be played during screenings, designed to enhance the emotional impact of the images. The score included patriotic songs like 'It's a Long Way to Tipperary' and 'Keep the Home Fires Burning,' which were played during scenes of marching soldiers. For battle sequences, theaters often used dramatic, martial music with drums and brass instruments to create tension and excitement. Solemn, melancholic pieces accompanied scenes of wounded soldiers and battlefield aftermath. Some theaters employed elaborate sound effects, including simulated artillery explosions and rifle fire, to enhance the viewing experience. The musical accompaniment was carefully synchronized with the film's action, creating an early form of multimedia presentation that significantly contributed to the film's emotional impact on audiences.

Famous Quotes

The picture is one of the finest things that has ever been done in the way of cinematography.

The Times, 1916

It brings home to us the reality of war in a way that no newspaper report can do.

Manchester Guardian, 1916

The film shows our men as they are - brave, cheerful, and determined to do their duty.

British War Office statement, 1916

Never before has the public been given such an opportunity of seeing what our soldiers are doing and suffering for us.

Film promotional material, 1916

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic 'over the top' sequence showing soldiers climbing out of trenches and advancing across no man's land, which became one of the most reproduced images of World War I

- The preparation scenes showing soldiers loading artillery pieces and moving supplies to the front lines, demonstrating the massive logistical effort behind the battle

- The footage of wounded soldiers being carried to medical stations, providing a stark contrast to the more heroic scenes of combat

- The sequence showing captured German prisoners being escorted to the rear, one of the few times enemy soldiers appear in the film

- The closing scenes of soldiers resting in captured trenches, suggesting both victory and exhaustion

Did You Know?

- The film was seen by an estimated 20 million people in Britain during its first two months of release, nearly half the country's population at the time

- It remains one of the most-watched British films in history, with ticket sales equivalent to over £50 million in modern currency

- The film was shown to King George V at Buckingham Palace on August 2, 1916, before its public release

- Some scenes showing soldiers going 'over the top' were staged for the camera as real combat was too dangerous to film

- The film caused public controversy when it was revealed that some combat scenes were re-enactments rather than actual footage

- Cinematographer Geoffrey Malins kept a detailed diary of his experiences filming the battle, which was later published as a book

- The film was distributed to neutral countries including the United States to help sway public opinion in favor of the Allies

- It was the first feature-length documentary to show real combat footage, setting a precedent for future war documentaries

- The film's success led to the creation of the War Office Cinematograph Committee to oversee future propaganda films

- Some soldiers who appeared in the film were identified by their families back home, leading to both joy and tragedy when their fates were learned

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's authenticity and emotional power, with The Times calling it 'a moving and impressive record of what our soldiers are doing and suffering for us.' The Manchester Guardian noted that 'the film brings home to us the reality of war in a way that no newspaper report can do.' Modern critics and film historians recognize the film as a landmark documentary, though they also acknowledge its role as propaganda. The British Film Institute describes it as 'probably the most seen and most controversial British film ever made.' Contemporary scholars debate the film's historical accuracy versus its propaganda value, but most agree on its technical achievement and cultural impact. The film is now studied as both a historical document and a pioneering work of documentary cinema, with particular attention paid to its complex relationship between truth and manipulation.

What Audiences Thought

The film was an unprecedented popular success, drawing enormous crowds across Britain when it premiered in August 1916. Many viewers were shocked by the realistic depiction of warfare, with some reports of audience members fainting or becoming ill during screenings. Despite the graphic content, the film was generally praised by the public for showing the reality of what their loved ones were experiencing at the front. The film created a shared national experience, becoming a topic of conversation in homes, workplaces, and pubs across the country. Some families recognized loved ones in the footage, leading to emotional reactions ranging from joy to grief. The film's popularity demonstrated cinema's emergence as a mass medium capable of reaching and influencing millions of people simultaneously. While some viewers questioned the authenticity of certain scenes, most accepted the film as a truthful representation of the war, and it succeeded in its goal of boosting public morale and support for the war effort.

Awards & Recognition

- Honorary recognition from the British War Office for contributions to the war effort

- Special Commendation from the British Film Institute for historical significance

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier British newsreels and actuality films

- Official war photography from the Crimean and Boer Wars

- Stage melodramas about warfare

- Contemporary newspaper war correspondence

- Government propaganda posters

This Film Influenced

- The Battle of the Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks (1917)

- The German Side of the Battle of the Somme (1917)

- The Battle of Ypres (1917)

- All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

- World War I documentary series throughout the 20th century

- Modern war documentaries including those from Vietnam and Iraq conflicts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been fully preserved and restored by the Imperial War Museum in London. A complete 35mm nitrate original exists in the museum's archives, along with multiple duplicate copies. The film underwent a major digital restoration in 2005 to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the battle, with damaged sections repaired and image quality enhanced. The restored version has been screened at film festivals and special events worldwide. The Imperial War Museum has made the film available for educational purposes and it remains one of the most frequently accessed items in their collection. The film's preservation status is considered excellent, with no risk of loss to this historically significant work.