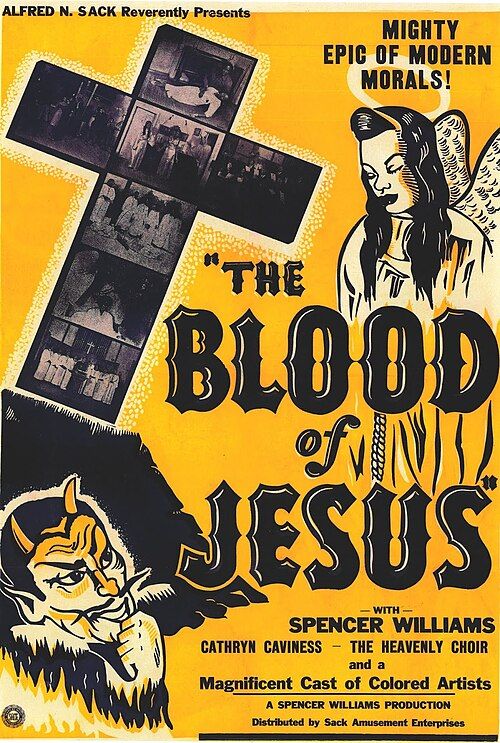

The Blood of Jesus

"A Heavenly Drama of Sin and Redemption"

Plot

When Razz accidentally shoots his wife Martha with his hunting rifle, the church congregation gathers to pray for her recovery at her bedside. During this prayer vigil, an angel arrives to take Martha's spirit from her body, but her journey to the afterlife is interrupted by the temptations of Judas Green, a slick devil's agent. Martha is led through a series of moral trials and temptations, including visits to a jazz club and other worldly pleasures that test her faith and devotion. The film presents a vivid allegorical battle between good and evil as Martha struggles between her spiritual calling and earthly temptations. Through divine intervention and her own unwavering faith, Martha ultimately resists the devil's temptations and is given a second chance at life. The film culminates with Martha's miraculous recovery and her rededication to a life of religious service and moral righteousness.

About the Production

Shot on a minuscule budget in approximately two weeks, the film utilized non-professional actors from local church communities and was financed by Alfred N. Sack, a white theater owner who specialized in distributing race films. The production faced significant challenges including limited equipment, basic lighting setups, and having to complete scenes quickly due to budget constraints. Despite these limitations, director Spencer Williams created elaborate fantasy sequences using simple but effective special effects techniques including double exposure and creative camera angles.

Historical Background

The Blood of Jesus was produced during a critical period in American history when segregation was legally enforced and Black filmmakers were systematically excluded from mainstream Hollywood. The film emerged from the 'race film' movement, which produced approximately 500 films between 1915 and 1950 specifically for Black audiences in segregated theaters. Released just months before the United States entered World War II, the film reflected the spiritual and moral concerns of Black communities facing both racial discrimination and the looming global conflict. The early 1940s also saw the Great Migration continuing to reshape American demographics, with many Black Americans moving from rural areas to cities, creating new challenges to traditional religious values that the film addresses. The film's emphasis on Christian redemption and moral fortitude resonated with audiences seeking spiritual guidance during uncertain times.

Why This Film Matters

The Blood of Jesus represents a cornerstone of African American cinema history and stands as one of the most important race films ever produced. The film provides invaluable insight into Black religious life, values, and artistic expression during the Jim Crow era, offering a rare authentic representation of Black spirituality from a Black perspective. Its preservation and recognition by the National Film Registry highlight its enduring cultural importance and artistic merit. The film influenced generations of Black filmmakers and continues to be studied in film schools as an example of how to create meaningful cinema with limited resources. Its blend of religious themes, musical elements, and social commentary created a template for future Black religious films. The movie's commercial success proved that there was a viable market for films addressing Black experiences and values, paving the way for future Black filmmakers. Today, it serves as both an entertaining spiritual drama and a crucial historical document of African American life and faith in the early 1940s.

Making Of

The production of The Blood of Jesus was a remarkable achievement given its extreme limitations. Spencer Williams, working with a budget of just $5,000, had to be incredibly resourceful in bringing his vision to life. The film was shot in sequence over approximately two weeks in Texas during the summer of 1941. Williams recruited many cast members from local church congregations in Dallas, which helped create authentic performances and genuine spiritual atmosphere. The fantasy sequences depicting heaven and hell were particularly challenging to film with limited resources; Williams used creative lighting, double exposure techniques, and painted backdrops to create otherworldly effects. The jazz club temptation scene was filmed in an actual local venue, adding realism to Martha's moral testing. The entire production was a labor of love for Williams, who was deeply committed to creating meaningful cinema for Black audiences that reflected their values and experiences while providing moral guidance and entertainment.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Blood of Jesus, while limited by budget constraints, displays remarkable creativity and technical innovation. Director of Photography Jack Whitman employed dramatic lighting techniques to distinguish between the earthly and spiritual realms, using soft, ethereal lighting for heaven sequences and harsher shadows for scenes of temptation. The film makes effective use of Dutch angles during moments of moral conflict and employs tracking shots to follow Martha's spiritual journey. Despite using basic equipment, the cinematography achieves professional-quality composition, particularly in the church scenes where the arrangement of congregants creates powerful visual symmetry. The fantasy sequences feature innovative special effects for their time, including double exposure to create ghostly apparitions and creative use of mirrors and glass to suggest supernatural phenomena.

Innovations

Despite its minimal budget, The Blood of Jesus achieved several notable technical innovations for independent filmmaking of its era. The film's fantasy sequences featured pioneering use of double exposure and matte painting techniques to create supernatural effects that rivaled bigger-budget productions. Spencer Williams developed creative solutions for special effects, including using smoke and mirrors to create ghostly apparitions and employing reverse photography for supernatural transitions. The film's sound recording techniques were innovative for race films, capturing clear dialogue and powerful musical performances with limited equipment. The production team also developed cost-effective lighting setups that could quickly transform ordinary locations into heavenly or hellish environments. These technical achievements demonstrated that creative filmmaking could overcome budget limitations, influencing subsequent independent filmmakers.

Music

The film's soundtrack is integral to its emotional impact and cultural authenticity, featuring powerful gospel music performed by actual church choirs from the Dallas area. The musical numbers include traditional spirituals and original compositions that advance the plot and reinforce the film's moral themes. The jazz club scene provides a musical contrast, featuring secular music that represents worldly temptation. The film's score was composed by J. Ernest Green, who cleverly used musical motifs to distinguish between good and evil characters. The sound quality, while limited by 1940s recording technology, effectively captures the passionate performances of the church singers. The soundtrack has been praised for its authentic representation of Black religious music and its role in establishing the film's spiritual atmosphere.

Famous Quotes

The Lord works in mysterious ways, and sometimes he gives us a second chance to make things right.

When the devil comes knocking at your door, you better have Jesus standing right behind you.

Prayer is the key that unlocks heaven's door, but faith is what keeps it open.

The blood of Jesus washes away all sin, but you have to be willing to step into the water.

Temptation is like a beautiful song, but if you listen too long, you'll forget the words to your own salvation.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening accident scene where Razz's hunting rifle discharges and shoots Martha, setting the spiritual journey in motion.

- The powerful prayer vigil at Martha's bedside where the entire church congregation comes together to seek divine intervention.

- The angel's arrival and Martha's spirit leaving her body, depicted through innovative special effects for the era.

- Martha's journey through the wilderness of temptation, where she encounters Judas Green and faces moral tests.

- The jazz club scene where Martha is tempted by worldly pleasures, featuring authentic period music and dancing.

- The heavenly sequences with ethereal lighting and angelic figures, creating a stark contrast with earthly temptations.

- Martha's final decision to reject temptation and embrace redemption, culminating in her miraculous recovery.

- The closing scene where Martha dedicates her life to God's service, bringing the moral arc full circle.

Did You Know?

- The Blood of Jesus was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1991 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance.

- Director Spencer Williams not only directed but also starred in the film as Razz, showcasing his multi-talented abilities in early Black cinema.

- The film was produced by Sack Amusement Enterprises, one of the few white-owned companies that specifically produced and distributed race films for Black audiences.

- Despite its tiny budget of only $5,000, the film became one of the most commercially successful race films of its era.

- The film's soundtrack features authentic gospel music performed by actual church choirs, adding to its spiritual authenticity.

- Many of the actors were amateurs recruited from local Dallas churches, contributing to the film's genuine religious atmosphere.

- The film was shot entirely in Texas, primarily in Dallas and Fort Worth, making it a significant piece of regional Black cinema history.

- The Blood of Jesus was one of the first race films to explicitly deal with themes of Christian morality and spiritual redemption.

- The film's fantasy sequences were considered technically ambitious for their budget, using innovative camera techniques to create supernatural effects.

- Spencer Williams would later gain fame as Andy Brown in the TV series 'The Amos 'n' Andy Show,' but considered his race films his most important work.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception in the Black press was overwhelmingly positive, with newspapers like the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier praising the film's moral message and artistic ambition. Critics particularly noted the film's authentic portrayal of Black religious life and its effective use of gospel music. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of low-budget filmmaking and an important cultural artifact. Film scholars have praised Spencer Williams' directorial skill in creating compelling fantasy sequences with minimal resources and his ability to blend entertainment with moral instruction. The film's selection for the National Film Registry brought renewed critical attention, with many reviewers noting its technical innovations and cultural significance. Contemporary critics often highlight the film's sophisticated use of allegory and its importance as an example of Black cinema created outside the Hollywood system.

What Audiences Thought

The Blood of Jesus was tremendously popular with its intended Black audience, becoming one of the most successful race films of its era. Black church congregations particularly embraced the film, often organizing group viewings and discussions about its moral themes. The film's blend of entertainment and spiritual guidance resonated deeply with audiences seeking positive representations of Black life and values. Many viewers reported being moved to tears by the film's depiction of faith and redemption. The film's popularity extended beyond its initial theatrical run, with it being shown in churches and community centers for decades after its release. Modern audiences continue to connect with the film's powerful themes and authentic performances, with it now being appreciated both as entertainment and as an important piece of cultural history.

Awards & Recognition

- Selected for National Film Registry (1991)

- Inducted into the Black Film Hall of Fame

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Biblical stories of temptation and redemption

- African American church traditions

- The plays of Langston Hughes

- Earlier race films dealing with religious themes

- European religious allegory films

- Black gospel music traditions

- The oral storytelling traditions of the Black church

This Film Influenced

- Later Black religious films of the 1940s and 1950s

- Tyler Perry's religious-themed films

- The Gospel films of the 1970s

- Modern Black Christian cinema

- Independent faith-based films

- Films dealing with spiritual journey themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Blood of Jesus was successfully preserved and restored by the Library of Congress after being selected for the National Film Registry in 1991. The restoration process involved locating the best surviving film elements and creating new preservation prints. The film exists in its complete form and has been digitally remastered for modern viewing. The restoration has helped ensure that this important piece of African American cinema history remains accessible to future generations. The restored version is maintained in the Library of Congress's film collection and has been made available through various educational and archival channels.