The Conquest of the Pole

Plot

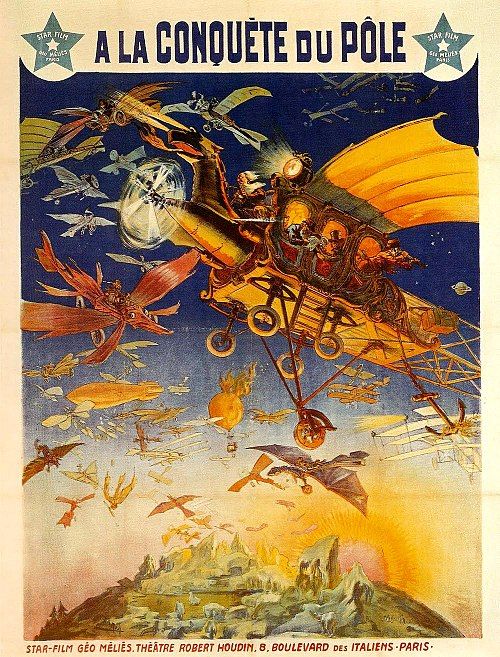

The Conquest of the Pole follows rival expeditions competing to be the first to reach the North Pole in a fantastical race featuring elaborate machinery and impossible vehicles. Professor Maboul leads one expedition using a massive airship called the 'Aerobus,' while his rivals employ various contraptions including a giant propeller-driven vehicle and a train-like machine that can travel across ice and snow. The journey is filled with spectacular visual effects as the explorers face giant ice monsters, strange Arctic phenomena, and mechanical failures in their desperate quest. After numerous adventures and disasters, Professor Maboul's expedition succeeds in planting their flag at the pole, only to discover it's inhabited by a giant man-eating snowman who must be defeated. The film concludes with the triumphant return of the survivors, celebrated as heroes for their conquest of the polar region.

Director

About the Production

This was one of Méliès' most ambitious productions, featuring elaborate sets and complex special effects. The giant snowman monster was created using actors in costumes and forced perspective techniques. The film required extensive miniature work for the various vehicles and Arctic landscapes. Méliès invested heavily in the production, creating one of his longest and most technically sophisticated films, but the changing tastes of audiences and the rise of more realistic filmmaking styles made it commercially unsuccessful.

Historical Background

The Conquest of the Pole was produced during a period of intense public fascination with polar exploration, following the successful expeditions of Robert Peary (claimed North Pole, 1909) and Roald Amundsen (South Pole, 1911). This 'Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration' captured the public imagination, and Méliès sought to capitalize on this interest with his characteristic fantastical approach. The film was also made during a transitional period in cinema history, as the industry was moving away from the theatrical, trick-film style that Méliès pioneered toward more narrative-driven, realistic filmmaking. In 1912, feature-length films were becoming more common, and the industry was increasingly dominated by American producers. Méliès, still working in the French tradition of short fantasy films, found himself increasingly out of step with these changes. The film's release also coincided with growing tensions in Europe that would eventually lead to World War I, which would dramatically alter the film industry and end Méliès' career entirely.

Why This Film Matters

The Conquest of the Pole represents both the culmination of Georges Méliès' cinematic techniques and the final chapter of his influential career. As one of the last major works from cinema's first great visionary, the film showcases the sophisticated special effects methods Méliès had developed over his career, including complex multiple exposures, elaborate miniatures, and innovative set designs. The film's blend of Jules Verne-inspired science fiction with contemporary exploration themes influenced later adventure and science fiction cinema, particularly in its depiction of fantastical vehicles and Arctic monsters. Despite its commercial failure, the film has been reassessed by film historians as a masterpiece of early special effects cinema, demonstrating Méliès' unparalleled creativity and technical skill. The film also serves as a poignant document of the transition from cinema's theatrical beginnings to its narrative future, with Méliès' failure to adapt marking the end of an era in filmmaking. Today, it is studied as an essential example of early fantasy cinema and as the swan song of one of film's founding fathers.

Making Of

The production of The Conquest of the Pole represented both the height of Méliès' technical prowess and the beginning of his decline as a filmmaker. Méliès invested heavily in creating elaborate sets representing the Arctic landscape, using painted backdrops and forced perspective to create vast, icy vistas. The various fantastical vehicles, particularly the giant airship 'Aerobus,' were built as full-scale props that could be moved and manipulated during filming. The most challenging aspect was creating the giant snowman monster, which required multiple performers working in coordination with complex camera tricks to achieve the desired scale effect. Méliès employed his signature substitution splices and multiple exposure techniques throughout the film, but also incorporated more sophisticated matte photography that was becoming standard in the industry. The production took several months, unusually long for the period, as Méliès strove to perfect every visual effect. Despite this attention to detail, the film's release coincided with a shift in audience preferences toward more realistic narratives and away from the theatrical, fantasy style that had made Méliès famous.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Conquest of the Pole showcases Georges Méliès' mastery of visual effects and his distinctive approach to cinematic storytelling. The film employs Méliès' signature techniques, including multiple exposure to create ghostly images and superimposed elements, substitution splices for magical appearances and disappearances, and elaborate matte shots to combine live action with painted backgrounds. The camera work is typically static, as was common in Méliès' films, allowing the focus to remain on the carefully choreographed action and special effects occurring within the frame. The film makes extensive use of forced perspective to create the illusion of giant creatures and vast Arctic landscapes, with actors positioned at different distances from the camera to achieve the desired scale effects. The lighting is theatrical and dramatic, with strong contrasts to highlight the magical elements and create a sense of wonder. The cinematography also incorporates sophisticated miniature work, with scale models of the various vehicles blended with full-size elements to create convincing fantastic machines. Despite the static camera, the frame is always filled with visual interest, with Méliès using every inch of the image to create his fantastical Arctic world.

Innovations

The Conquest of the Pole represents some of the most sophisticated technical achievements of Georges Méliès' career, pushing the boundaries of what was possible in early special effects cinema. The film features complex multiple exposure sequences, particularly in scenes involving the various fantastic vehicles and the giant snowman monster, requiring precise timing and registration to create convincing composite images. Méliès employed advanced matte photography techniques to blend actors with miniature sets and painted backgrounds, creating seamless transitions between different scales and environments. The film's elaborate miniature work, including the various Arctic exploration vehicles, demonstrated Méliès' mastery of forced perspective and scale modeling. The creation of the giant snowman required innovative use of perspective tricks and coordinated performances by multiple actors to achieve the illusion of a massive creature. The film also showcases Méliès' sophisticated use of substitution splices, with carefully timed cuts creating magical transformations and appearances. The complex set designs, featuring movable ice formations and mechanical elements, represented significant advances in stagecraft for film production. Perhaps most impressively, Méliès managed to coordinate these various technical elements into a coherent 33-minute narrative, far longer than most of his previous works and requiring unprecedented planning and execution.

Music

As a silent film, The Conquest of the Pole would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have featured a pianist or small orchestra performing popular classical pieces, marches, and specially composed cues timed to match the on-screen action. For the Arctic scenes, music might have included dramatic, cold-sounding compositions, while the fantastic elements would have been highlighted with whimsical or mysterious melodies. The race sequences would have been accompanied by energetic marches or galops to create excitement and tension. Unfortunately, no specific musical scores or cue sheets for the film have survived, so modern screenings typically use appropriate period music or newly composed scores. Some contemporary restorations have featured original compositions by silent film accompanists who specialize in creating historically informed musical accompaniments for early cinema. The lack of synchronized sound allowed for flexibility in musical interpretation, with each theater's musical director able to adapt the performance to local tastes and the specific audience response.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, The Conquest of the Pole featured intertitles rather than spoken dialogue. Key intertitles included: 'A race to the North Pole!', 'Professor Maboul's incredible Aerobus', 'The monster of the ice!', 'Victory! We have conquered the Pole!'

Memorable Scenes

- The launch of Professor Maboul's giant airship 'Aerobus' with its elaborate propellers and balloon structure

- The various rival expeditions setting off with their fantastic machines, including a giant propeller-driven vehicle and a snow train

- The appearance of the giant snowman monster, created using forced perspective and multiple performers

- The battle with the snowman, featuring Méliès' signature special effects as the explorers fight the creature

- The final planting of the flag at the North Pole with the defeated monster in the background

Did You Know?

- This was Georges Méliès' penultimate film before he was forced out of business

- The film was loosely based on Jules Verne's 1864 novel 'The Adventures of Captain Hatteras'

- The giant snowman monster was one of Méliès' most elaborate creature creations, requiring multiple performers and complex rigging

- At 33 minutes, it was unusually long for a Méliès film, most of which were under 15 minutes

- The film features some of Méliès' most complex special effects, including multiple exposure, matte shots, and substitution splices

- Despite its technical brilliance, the film represented Méliès' failure to adapt to changing cinematic tastes

- The various fantastic vehicles in the film were inspired by both contemporary Arctic expeditions and Méliès' boundless imagination

- The film was released in both French and English versions to appeal to international markets

- Many of the Arctic expedition props and sets were reused from Méliès' earlier films

- The film's commercial failure contributed to Méliès losing his studio in 1913

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to The Conquest of the Pole was mixed, with many reviewers noting the film's technical brilliance while criticizing its outdated theatrical style. The French trade journal Ciné-Journal praised Méliès' 'inimitable imagination' but noted that audiences were becoming tired of his formulaic approach. British reviewers in The Bioscope acknowledged the film's 'clever trick photography' but found the narrative lacking compared to more realistic adventure films. Modern critics have been much more appreciative, with film historian Georges Sadoul calling it 'one of Méliès' most ambitious and visually spectacular works.' Contemporary scholars often cite the film as a prime example of Méliès' mastery of special effects and his unique contribution to early cinema language. The film is now frequently included in retrospectives of Méliès' work and early science fiction cinema, with many modern critics praising its imaginative vision and technical innovation despite its initial commercial failure.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to The Conquest of the Pole in 1912 was disappointing, contributing significantly to the film's commercial failure and Méliès' subsequent financial troubles. Contemporary audiences, who had once eagerly embraced Méliès' magical trick films, had by 1912 developed a taste for more realistic narratives and sophisticated storytelling. The film's theatrical style and obvious stage-bound sets, which had charmed early cinema audiences, now appeared dated and artificial to viewers accustomed to the growing realism of American and European films. Many audience members found the film's length (at 33 minutes, unusually long for a Méliès production) tedious compared to the shorter, more dynamic films being produced by competitors. The poor reception was particularly disheartening for Méliès as it represented a complete reversal of his earlier popularity, when films like 'A Trip to the Moon' (1902) had been international sensations. Modern audiences, however, viewing the film through the lens of film history, tend to appreciate its imaginative qualities and technical achievements, with the film often receiving enthusiastic responses at special screenings and retrospectives.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Adventures of Captain Hatteras by Jules Verne

- Contemporary Arctic exploration accounts

- Earlier Méliès fantasy films including A Trip to the Moon

- Stage magic and theatrical traditions

- Scientific romances of the late 19th century

This Film Influenced

- Metropolis (1927) - in its depiction of fantastic machines

- Things to Come (1936) - in its vision of technological progress

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) - in its adaptation of Verne's work

- The Golden Age of science fiction cinema of the 1950s

- Modern adventure films featuring polar exploration

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Conquest of the Pole survives in its entirety and has been preserved by several film archives, including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. A restored version was released in the early 2000s as part of the comprehensive Méliès restoration project, with color elements reconstructed from original hand-painted prints. The film exists in both black and white and partially colorized versions, with the color version featuring Méliès' characteristic stencil coloring techniques. While some deterioration is visible in surviving prints, particularly in the color sequences, the film remains largely intact and viewable. The restoration work has helped preserve the film's elaborate visual effects and detailed sets for modern audiences. The film is considered one of the better-preserved works from Méliès' later period, likely due to its relative importance in his filmography and its distribution in multiple countries, which increased the chances of survival.