The Demolition of the Russian Monument at St Stephen

Plot

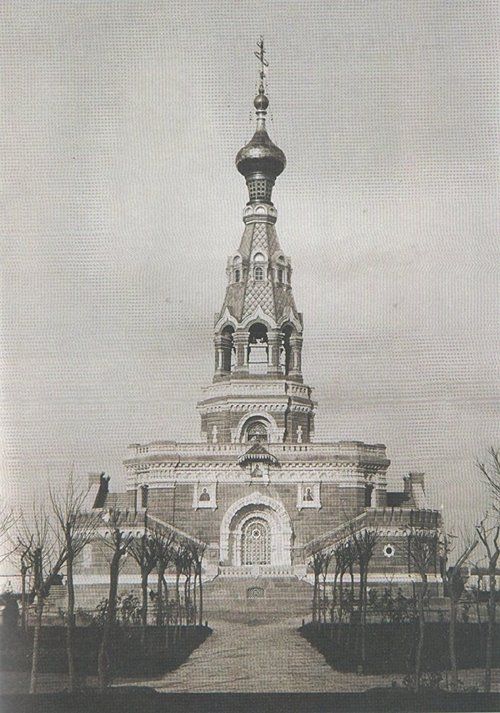

This historic documentary short film captures the demolition of a Russian monument located at St. Stephen (Büyükada) in Istanbul shortly after the Ottoman Empire entered World War I. The film documents Turkish soldiers and civilians working together to remove the monument, which stood as a symbol of Russian influence in the region. The demolition was ordered as an act of defiance against Russia, with whom the Ottoman Empire had just entered into conflict. The camera records the systematic destruction of the monument, showing the tools and methods used in its removal. The footage serves as both a propaganda piece and a historical record of the patriotic fervor sweeping through Istanbul at the war's outset.

Director

About the Production

This film was commissioned by Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Minister of War, as part of the newly established Central Cinema Directorate. Fuat Uzkınay, a reserve army officer with the 3rd Army, was given the task of documenting this event. The filming took place on November 14, 1914, just weeks after the Ottoman Empire entered World War I. The camera used was likely a Pathé or Gaumont model, commonly available to military photographers of the era. The demolition itself was a significant political statement, as the monument had been erected to commemorate Russian sailors who died in the Ottoman Empire.

Historical Background

This film was created during a pivotal moment in world and Turkish history. November 1914 marked the Ottoman Empire's entry into World War I, a conflict that would ultimately lead to the empire's dissolution and the birth of modern Turkey. The film documents the immediate aftermath of this decision, capturing the anti-Russian sentiment that swept through Istanbul. The Russian monument itself had been erected decades earlier to commemorate Russian sailors who died during a cholera outbreak while their fleet was anchored in Ottoman waters. Its demolition symbolized the complete break between the two empires, which had been rivals for centuries. The film also represents the Ottoman military's early recognition of cinema's power as a propaganda medium, following the example of European powers who were already using film extensively for war documentation and recruitment.

Why This Film Matters

As the first Turkish film, this work holds immense cultural and historical importance for Turkish cinema. It represents the birth of a national film industry that would grow to become one of the most prolific in the world. The film established several precedents: it demonstrated that cinema could serve national and military purposes, it showed that Turkish subjects were worthy of being filmed, and it proved that Turks could operate cameras and create moving images themselves. The film also marked the beginning of the relationship between the Turkish state and cinema, a dynamic that would continue throughout the 20th century. For decades, Turkish filmmakers have looked back to Uzkınay's work as the foundation of their national cinema. The film's documentary style and patriotic themes would influence early Turkish cinema for years to come.

Making Of

The making of this film was directly tied to the outbreak of World War I and the Ottoman Empire's decision to join the conflict on the side of the Central Powers. Enver Pasha, recognizing the power of cinema as a propaganda tool, established the Central Cinema Directorate and tasked Fuat Uzkınay with documenting significant war-related events. Uzkınay, who had experience with still photography, was given a movie camera and minimal training. The demolition of the Russian monument was chosen as an ideal subject because it symbolized the break with Russia and could be filmed safely in Istanbul. The filming process was rudimentary by modern standards - Uzkınay likely operated a hand-cranked camera, manually exposing each frame. The entire production was overseen by military officials who wanted to ensure the footage served their propaganda purposes. Despite these limitations, Uzkınay managed to capture clear, steady footage that documented the event comprehensively.

Visual Style

The cinematography of this film reflects the limitations and practices of early documentary filmmaking. Shot on what was likely a hand-cranked 35mm camera, the footage exhibits the characteristic stationary shots and long takes of newsreel-style cinematography of the 1910s. Uzkınay, working with minimal experience, employed straightforward, observational camera positioning, likely setting up his camera at a distance to capture the entire demolition process. The black and white footage shows the high contrast and occasional overexposure common in early film stock. Despite these technical limitations, the framing demonstrates an awareness of composition, with the monument positioned prominently within the frame. The camera work is steady and functional, prioritizing clear documentation over artistic expression. The cinematography serves its purpose effectively, providing a clear visual record of the historical event.

Innovations

While technically rudimentary by modern standards, this film represented several important achievements for its time and place. It was the first film shot by a Turkish director, marking a significant milestone in the development of indigenous film production in the Ottoman Empire. The successful documentation of a real-time event demonstrated that Turkish filmmakers could handle the technical challenges of location shooting and documentary work. The film also showed that the Ottoman military could organize and execute film production for propaganda purposes, establishing a model for future wartime filmmaking. The preservation of footage from this period is itself a technical achievement, given the fragility of early film stock and the political upheavals that followed in the region. The film's existence proves that cinematic technology had reached and was being utilized in the Ottoman Empire by the early 1910s.

Music

This film was produced during the silent era and contained no synchronized soundtrack. Like most films of 1914, it would have been accompanied by live music during screenings. For military or government screenings, this likely consisted of patriotic Ottoman military music or popular songs of the period. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to enhance the film's propaganda value, with triumphant or martial themes accompanying the demolition scenes. In some cases, a narrator might have provided live commentary explaining the significance of what was being shown. The absence of recorded sound was typical for the era, and the film's documentary nature made it particularly suitable for live musical adaptation based on the screening context.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue - silent film with no intertitles documented

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic moment when the Russian monument finally topples after workers have been chipping away at its base with tools and ropes, capturing the symbolic destruction of Russian influence in Ottoman territory

Did You Know?

- This is widely considered the first Turkish film ever made, marking the birth of Turkish cinema

- Director Fuat Uzkınay was actually a reserve army officer, not a professional filmmaker

- The film was shot just 10 days after the Ottoman Empire entered World War I

- The Russian monument being demolished was a memorial to Russian sailors who had died of cholera in the 19th century

- Enver Pasha, who commissioned the film, was one of the 'Three Pashas' who led the Ottoman Empire during WWI

- The film was originally intended as propaganda to boost morale and show Turkish resistance to Russian influence

- Only fragments of the original film are believed to survive today

- The demolition took place on Büyükada, one of the Princes' Islands in the Sea of Marmara

- Uzkınay would go on to establish the first Turkish film studio and direct over 100 films

- The film's existence helped establish the Ottoman War Department's Central Cinema Directorate, the first official film production unit in Turkey

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception is difficult to document due to the film's nature as a military production and the limited film press in the Ottoman Empire at the time. However, military officials and government authorities reportedly viewed the footage favorably, considering it successful in its propaganda mission. Modern film historians and critics recognize the film primarily for its historical significance rather than its artistic merits. Film scholars view it as a crucial document marking the birth of Turkish cinema, though they note that its value lies more in its existence than in its cinematic technique. The film is often discussed in academic works about early cinema and the development of national film industries, where it is typically analyzed in the context of wartime propaganda and the emergence of cinema in non-Western countries.

What Audiences Thought

The film was not shown to general commercial audiences in the modern sense, as it was produced for military and governmental purposes. It was likely screened for military officials, government personnel, and possibly at patriotic gatherings in Istanbul during the early months of World War I. Contemporary audiences who did see the footage reportedly responded with patriotic enthusiasm, as the demolition of the Russian monument was a popular act that resonated with anti-Russian sentiment following the outbreak of war. The film served to reinforce existing nationalist feelings and validate the Ottoman Empire's decision to enter the conflict. Today, the film is viewed primarily by film historians, students of cinema, and those interested in Turkish history, with audiences appreciating its historical value over its entertainment content.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European war newsreels

- Early documentary films

- Military propaganda films

- Pathé newsreels

This Film Influenced

- Early Turkish documentaries

- Ottoman wartime propaganda films

- Turkish historical documentaries

- Military training films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with only fragments surviving today. Some footage exists in the Turkish State Archives, though the complete original version is believed to be lost. The surviving material has been restored and digitized by film preservationists, making it accessible for historical study. The fragmentary nature of the survival is typical for films from this era and region, given the political upheavals, wars, and technological limitations of film preservation in the early 20th century.