The Dull Sword

Plot

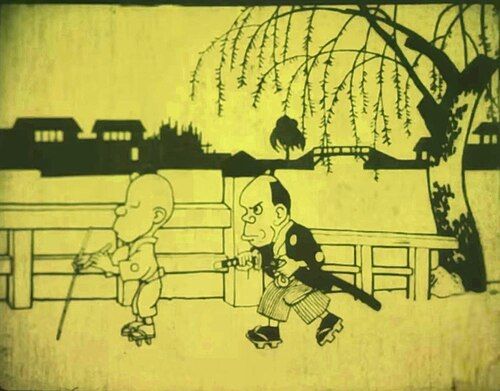

A foolish samurai purchases a new sword from a merchant, excited about his acquisition. When he attempts to test the blade by cutting various objects, he discovers to his horror that the sword is completely dull and cannot cut anything. Enraged by this deception, the samurai storms back to confront the merchant who sold him the useless weapon. In an unexpected twist, the seemingly weak and dull-looking merchant reveals himself to be a master swordsman, effortlessly defeating the samurai and demonstrating that skill matters more than the quality of one's weapon. The film concludes with the humiliated samurai learning a valuable lesson about judging appearances and the importance of true martial ability.

Director

Junichi KouchiAbout the Production

Created using cutout animation techniques typical of early Japanese animation. The film was produced on 35mm film and was likely hand-colored frame by frame, a common practice for Japanese animated works of this period. The animation was created by cutting out paper figures and moving them between shots to create the illusion of movement.

Historical Background

The Dull Sword was created in 1917, during the Taishō period in Japan, a time of significant modernization and Western influence. This was just over a decade after Japan's first animated films appeared, making it part of the foundational generation of Japanese animation. The film industry in Japan was rapidly expanding, with both live-action and animated films gaining popularity. World War I was ongoing, though Japan's involvement was limited, allowing cultural industries to flourish. The film reflects the blending of traditional Japanese themes (samurai culture) with modern cinematic techniques. This period saw the emergence of the first Japanese animation studios and the development of uniquely Japanese animation styles that would eventually evolve into modern anime.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest surviving examples of Japanese animation, The Dull Sword holds immense historical importance for understanding the origins of anime. It demonstrates that from its earliest days, Japanese animation incorporated elements of traditional Japanese culture and humor. The film's survival is particularly significant because most early Japanese animated works have been lost due to the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, which destroyed many film archives, and the general deterioration of early nitrate film stock. The rediscovery of this film in 2008 was a major event for film historians and anime scholars. It serves as a crucial link between traditional Japanese art forms and the modern anime industry, showing how early animators adapted cultural stories to the new medium of animation.

Making Of

The Dull Sword was created during the very infancy of Japanese animation, when most animated works were short films shown in theaters before main features. Director Junichi Kouchi was among the first generation of Japanese animators, having learned his craft from studying foreign animated films. The production used cutout animation techniques, where paper figures were cut out and manually moved between exposures to create movement. This method was cheaper and faster than the cel animation that would later become standard. The film was likely created by a very small team, possibly just Kouchi himself working with an assistant. The humor and visual style were heavily influenced by Japanese manga and traditional comedic storytelling, while also borrowing from Western silent film comedy traditions.

Visual Style

The film employs simple but effective black and white cinematography typical of the silent era. The animation uses cutout techniques with paper figures moved against static backgrounds. The visual style is minimalist but expressive, with characters designed in a way that emphasizes their comedic roles. The samurai is drawn with exaggerated features to emphasize his foolishness, while the merchant has an unassuming appearance that makes his transformation more surprising. The cinematography makes effective use of close-ups for comedic moments and wider shots for action sequences. Despite the technical limitations of 1917 animation technology, the film demonstrates good understanding of visual storytelling and timing.

Innovations

The Dull Sword represents an important technical achievement in early Japanese animation through its use of cutout animation techniques. The film demonstrates sophisticated understanding of timing and movement for its era, with smooth character motions that effectively convey action and emotion. The animators successfully created a coherent narrative with clear character development using limited animation techniques. The film's preservation and restoration have also been technically significant, allowing modern audiences to view this rare example of early Japanese animation. The work showcases how early animators overcame technical limitations to create engaging entertainment with minimal resources.

Music

As a silent film from 1917, The Dull Sword originally had no synchronized soundtrack. During theatrical screenings, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small ensemble playing appropriate mood music. The musical accompaniment would have followed the conventions of silent film scoring, with upbeat music for comedic moments and dramatic music during action sequences. Modern screenings and restorations of the film often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music to recreate the silent film experience. Some contemporary presentations have used traditional Japanese instruments to enhance the cultural context of the animation.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but intertitles would have conveyed key moments like 'A new sword!' and 'It won't cut!')

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where the samurai tries to test his new sword on various objects, only to have the blade fail completely, leading to his growing frustration and eventual rage - this sequence demonstrates early mastery of comedic timing and visual storytelling in animation.

Did You Know?

- This is one of the oldest surviving Japanese animated films in existence

- The original Japanese title is 'Namakura Gatana' (なまくら刀)

- The film was discovered in an antique shop in Osaka in 2008

- It was directed by Junichi Kouchi, one of Japan's first anime pioneers

- The film uses cutout animation technique rather than cel animation

- Only about 3 minutes of the original footage survive today

- It was screened alongside live-action films in theaters as a short subject

- The film represents early Japanese comedic animation traditions

- It predates what many consider the 'golden age' of Japanese animation by several decades

- The merchant character's transformation from weak to powerful was a common trope in early Japanese storytelling

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception from 1917 is not documented, as film criticism was still developing in Japan during this period. However, modern film historians and animation scholars have praised The Dull Sword as an important artifact of early Japanese animation. Critics note its sophisticated use of cutout animation and its effective comedic timing despite the technical limitations of the era. The film is often cited in academic discussions about the origins of anime and how early Japanese animators developed their unique visual language. Animation historians particularly appreciate how the film combines traditional Japanese storytelling with emerging cinematic techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Original audience reception from 1917 is not recorded in historical documents, but the film's survival suggests it was popular enough to be preserved and shown multiple times. As a short comedy subject, it likely entertained theater audiences of the time who were experiencing the novelty of animation. Modern audiences viewing the restored film often express fascination with seeing such an early example of Japanese animation, appreciating both its historical value and its surprisingly effective humor that still works over a century later. The film has been featured in retrospectives of early animation, where contemporary viewers have responded positively to its charm and historical significance.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Japanese folk tales

- Early American silent comedies

- Japanese manga traditions

- Samurai literature and theater

This Film Influenced

- Early Japanese animated shorts

- Modern samurai comedy anime

- Japanese animation comedy traditions

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for decades until its rediscovery in an antique shop in Osaka in 2008. It has since been restored and digitized by Japanese film preservation organizations. While not complete, the surviving footage represents most of the original film. It is now preserved in the National Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and has been made available for scholarly study and public exhibition.