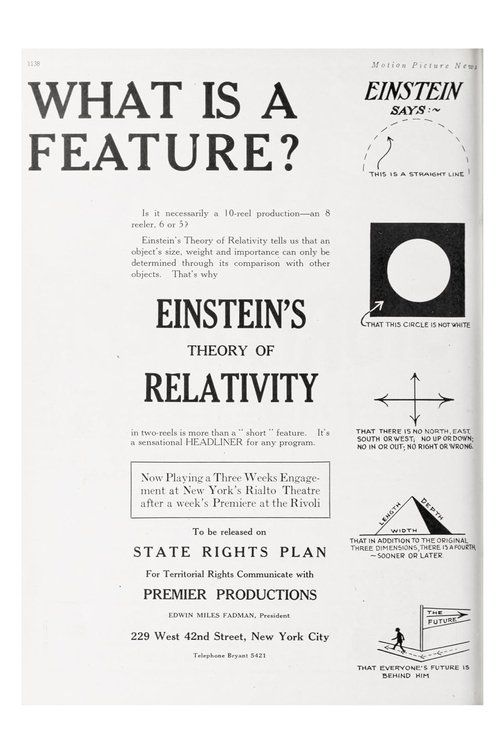

The Einstein Theory of Relativity

"The Greatest Scientific Discovery of the Age Explained Through Animation"

Plot

This groundbreaking educational documentary uses innovative animation techniques to explain Albert Einstein's revolutionary theory of relativity in accessible terms. The film visualizes complex scientific concepts through animated sequences, demonstrating how space and time are interconnected and how gravity affects the fabric of spacetime. Through a series of carefully crafted animated diagrams and illustrations, the film breaks down both special and general relativity for a general audience. The animation serves as a visual aid to help viewers understand abstract concepts like time dilation, length contraction, and the bending of light around massive objects. The film represents one of the earliest attempts to use animation for scientific education, making complex physics comprehensible to the masses.

Director

About the Production

This film was created using the innovative rotoscoping and animation techniques pioneered by the Fleischer brothers. The production involved translating complex scientific concepts into visual animations that could be understood by general audiences. Dave Fleischer worked closely with scientific advisors to ensure accuracy while maintaining visual appeal. The animation was hand-drawn on paper cells and photographed frame by frame, a labor-intensive process for the time.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a period of tremendous scientific and cultural change in the early 1920s. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity had captured the public imagination following the 1919 solar eclipse expedition that provided experimental evidence supporting his theories. The 1920s saw a surge in popular interest in science, with newspapers and magazines regularly covering new discoveries. The film industry was also transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, though educational shorts remained important for both theatrical and non-theatrical distribution. This period also saw the rise of animation as a legitimate art form, with studios like Fleischer and Disney pioneering new techniques. The film reflects the modernist spirit of the age, embracing new scientific understanding and innovative artistic techniques to educate and entertain audiences.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the first attempts to use animation for serious scientific education. It demonstrated that animation could be more than just entertainment - it could be a powerful tool for visualizing abstract concepts and making complex knowledge accessible to general audiences. The film paved the way for future educational animations and science documentaries, influencing how scientific concepts would be presented visually for decades to come. It also represents an early example of cross-cultural scientific communication, adapting a German educational film for American audiences during a period when scientific knowledge was rapidly spreading internationally. The film's survival despite the loss of both its German predecessor and American long version makes it an important artifact of early educational cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'The Einstein Theory of Relativity' represented a significant challenge for the Fleischer studio, as they had to translate highly complex scientific concepts into visual form that could be understood by audiences with no scientific background. Dave Fleischer and his team worked closely with physics experts to ensure the accuracy of their animated representations. The animation process involved creating hundreds of individual drawings showing the movement of objects through space, the bending of light, and the warping of spacetime. The studio used their patented rotoscoping technique to create smooth, realistic motion for the animated sequences. The project was considered ambitious for its time, as educational films were rare and animation was primarily used for entertainment purposes.

Visual Style

The cinematography of this animated short focused on clarity and precision in presenting scientific concepts. The animation used bold lines and contrasting colors to ensure that complex diagrams and demonstrations would be clear to viewers. The camera work was straightforward, primarily static shots of the animated sequences, allowing the educational content to take center stage. The animators paid careful attention to the timing and spacing of movements to accurately represent physical phenomena. The visual style was clean and modern, reflecting the scientific subject matter while remaining accessible to non-technical audiences.

Innovations

This film represented several technical achievements for its time. It was among the first to use animation specifically for scientific visualization, requiring the development of new techniques for representing abstract concepts visually. The Fleischer studio employed their innovative rotoscoping technology to create smooth, realistic motion in the animated sequences. The film demonstrated sophisticated understanding of how to use visual metaphor and analogy to explain complex scientific ideas. The animation techniques used to show the bending of light and warping of spacetime were particularly innovative and influenced how these concepts would be visualized in future educational materials.

Music

As a silent film from 1923, the original production would have been accompanied by live musical performance. The score would likely have been classical or light orchestral music typical of educational presentations of the era. The music would have been chosen to enhance the educational atmosphere without distracting from the complex visual information being presented. In modern restorations, appropriate period music has been added to recreate the silent film experience.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue - silent film with intertitles explaining the concepts

Memorable Scenes

- The animated sequence showing how massive objects warp the fabric of spacetime, using a grid that bends around celestial bodies to demonstrate gravity's effect on space and time.

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest examples of animation being used for educational purposes rather than entertainment

- The film was produced during Einstein's rise to international fame following the 1919 eclipse observations that confirmed his theory

- Dave Fleischer would later become famous for creating Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons

- The original German version was directed by Hanns Walter Kornblum and featured Einstein himself in some sequences

- Both the original German feature and the American long version are considered lost films

- The surviving short version was preserved through the efforts of film archivists in the 1970s

- The film demonstrates early use of what would later become motion graphics in educational filmmaking

- Einstein's theories were still controversial and not fully accepted by all scientists when this film was made

- The Fleischer studio was known for technical innovation, including the rotoscope device invented by Max Fleischer

- This film predates Disney's educational shorts by over a decade

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film for its innovative approach to making complex scientific concepts accessible through animation. Critics noted the clever use of visual metaphors and the clarity of the animated demonstrations. Scientific publications of the time commended the accuracy of the representations while acknowledging the necessary simplifications for public understanding. Modern film historians and animation scholars recognize the film as a pioneering work in educational animation, though it remains relatively obscure compared to the entertainment cartoons of the era. The film is often cited in academic discussions of early documentary film and the use of animation in science communication.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences interested in science and new discoveries, which was a significant portion of the theater-going public in the 1920s. Viewers appreciated the visual approach to understanding concepts that were difficult to grasp through text alone. The animation made abstract ideas concrete and memorable, helping to popularize Einstein's theories among the general public. The film was particularly popular in educational settings and was often booked for special screenings at schools, universities, and scientific societies. Its success demonstrated that there was an audience for serious, educational content in theaters, not just entertainment.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented - educational shorts of this era rarely received formal recognition

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German educational films of the 1920s

- Scientific illustration traditions

- Early animation techniques

- Educational lantern slides

- Scientific textbooks and diagrams

This Film Influenced

- Later educational animation series

- Science documentary visualizations

- Modern educational YouTube channels

- NASA educational animations

- PBS science programming

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - the short version (587 meters) survives in film archives, while both the original German feature and the American long version (1219 meters) are considered lost films. The surviving version has been restored and preserved by major film archives.