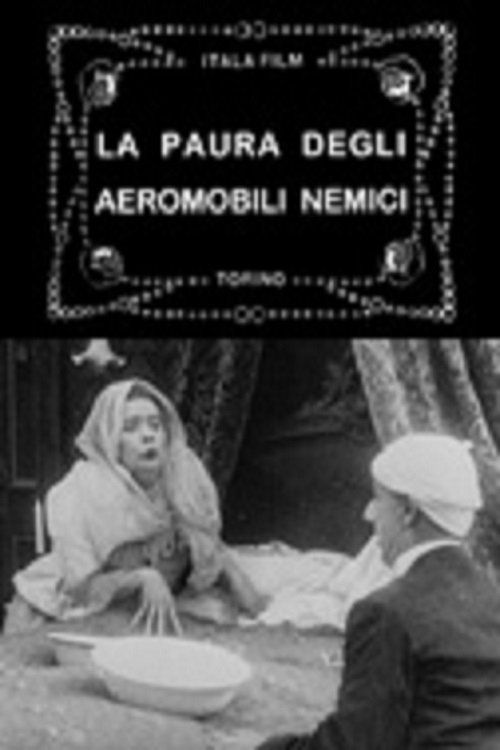

The Fear of Zeppelins

Plot

Cretinetti, the beloved comic character portrayed by André Deed, is ecstatically preparing for his wedding day to his statuesque bride-to-be. However, his joy is abruptly interrupted when he discovers a public notice detailing emergency procedures for enemy air raids, specifically zeppelin attacks. The notice triggers an overwhelming paranoia in Cretinetti, causing him to interpret the safety instructions with absurd literalness and implement them with disastrous results. His overzealous precautions create a cascade of accidents and chaos that not only ruin his wedding night but ultimately lead to the complete destruction of his house. The film culminates with gendarmes arriving at the ruins to conscript Cretinetti for military service, dragging him away to war under the horrified gaze of his new wife, leaving both his marriage and home in ruins.

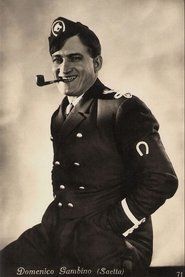

Director

About the Production

This film was produced during the height of World War I when Italy was initially neutral but facing growing pressure to join the Allies. The production had to contend with wartime resource shortages and the real threat of air raids that the film satirizes. Director and star André Deed, a French actor working in Italy, brought his popular Cretinetti character to address contemporary wartime anxieties through comedy. The film likely used studio sets for the house destruction sequence, a common practice in Italian cinema of the period.

Historical Background

This film was produced in 1915 during a pivotal moment in World War I, when zeppelin air raids were a new and terrifying form of warfare being employed by Germany against civilian targets. The first zeppelin raid on London had occurred in January 1915, and these massive airships became symbols of technological terror and the changing nature of warfare. Italy was still neutral during the film's production but would join the Allies in May 1915, making the film's themes of conscription and wartime anxiety particularly prescient. The film represents how cinema of the period directly engaged with contemporary fears and events, using comedy as a vehicle to process and satirize the anxieties of modern warfare. Early cinema was rapidly evolving from simple novelty acts to sophisticated narrative forms, and films like this demonstrate how filmmakers were beginning to address complex social and political themes through popular entertainment. The Cretinetti character, created by Deed, was one of the earliest recurring comic characters in cinema, predating even Chaplin's Tramp in terms of international recognition.

Why This Film Matters

The Fear of Zeppelins represents an important example of how early cinema responded to and processed contemporary wartime anxieties through comedy. As one of the Cretinetti series films, it contributed to the development of the recurring comic character format that would become fundamental to cinema comedy. The film's satirical approach to wartime fears demonstrates cinema's emerging role as a social commentator and emotional outlet for audiences dealing with the stresses of modern warfare. André Deed's work in Italy helped establish international comedy conventions and influenced later comedians including Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. The film also illustrates the transnational nature of early cinema, with a French actor creating content for Italian studios that would be distributed globally. The use of contemporary technological fears (zeppelins) as comedic material shows how quickly cinema adapted to reflect modern life and concerns. This film, along with others in the Cretinetti series, helped establish physical comedy as a universal language of cinema that could transcend cultural and linguistic barriers.

Making Of

The production of 'The Fear of Zeppelins' took place at the height of André Deed's popularity in Italian cinema. Deed, a French comedian who had found tremendous success in Italy, brought his signature physical comedy style to this wartime satire. The film was shot at the Itala Film studios in Turin, which were among the most advanced production facilities in Europe at the time. The house destruction sequence required careful planning and likely used a combination of full-scale sets and miniature models, techniques that Italian studios had perfected in their historical epics. The timing of the production was particularly poignant, as Italy was debating entry into World War I, and the fear of air raids was very real for European civilians. Director André Deed also served as the film's star, bringing his intimate understanding of the Cretinetti character's physical comedy and timing to both sides of the camera. The supporting cast, including Deed's wife Leonie Laporte, was drawn from the regular troupe of actors who frequently appeared in the Cretinetti series.

Visual Style

The cinematography for this 1915 production would have utilized the standard techniques of the era, likely filmed with hand-cranked cameras creating variable frame rates that enhanced the comic timing. The film probably employed static camera positions typical of early cinema, with careful blocking of action within the frame. The destruction sequences may have used multiple camera angles and editing techniques to create the illusion of catastrophic damage. Italian studios of this period were known for their technical sophistication, and the film likely benefited from good lighting and set design. The visual style would have emphasized clarity of action to ensure the physical comedy was easily understood by audiences. The film may have used some special effects techniques for the house destruction, possibly including matte shots or miniatures, reflecting the technical expertise of Italian production companies.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical achievements typical of Italian cinema of the period. The house destruction sequence likely involved sophisticated special effects techniques including the use of miniatures, careful editing, and possibly matte photography to create the illusion of catastrophic damage. The production benefited from the advanced studio facilities of Itala Film in Turin, which were among the best in Europe. The film's pacing and editing reflect the growing sophistication of narrative construction in early cinema, with clear cause-and-effect relationships driving the comedic escalation. The use of contemporary props and references to air raid procedures shows attention to realistic detail within the comic framework. The film's distribution across multiple countries with different intertitles demonstrates the emerging international distribution networks of early cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Fear of Zeppelins' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibitions. The typical accompaniment would have been provided by a pianist or small orchestra using compiled music appropriate to the action on screen. Comic sequences would have been accompanied by light, playful music, while moments of panic and destruction might have used more dramatic or chaotic musical selections. The wartime theme might have been reflected through the inclusion of popular patriotic songs or military marches. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial in establishing mood and enhancing the comic timing of André Deed's physical performance. Some theaters might have used special sound effects, particularly during the air raid panic sequences, to heighten the audience's experience.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'Instructions for Air Raid: Remain calm and follow these procedures...'

(Intertitle) 'Cretinetti takes everything literally, especially danger warnings'

(Intertitle) 'A wedding day interrupted by the shadow of war'

(Intertitle) 'Safety first, even if it destroys everything else'

(Intertitle) 'From wedding bells to war bells in one day'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening wedding preparation scene where Cretinetti's happiness is palpable before discovering the air raid notice

- The moment Cretinetti reads the air raid instructions and his face transforms from joy to terror

- The escalating sequence of 'safety measures' that gradually destroy the house room by room

- The climactic house collapse that coincides with the arrival of the conscription officers

- The final shot of Cretinetti being dragged away to war while his new bride watches in horror

Did You Know?

- André Deed's character Cretinetti was known by different names in various countries - 'Fricot' in France, 'Cretinetti' in Italy, and 'Gribouille' in some markets

- The film was produced during a real period of zeppelin anxiety - German airships were conducting bombing raids on European cities during WWI

- André Deed was one of the highest-paid film comedians of his time, earning a salary comparable to Charlie Chaplin in the early 1910s

- The destruction of the house in the finale was likely achieved through careful editing and miniature effects, techniques pioneered by Italian studios

- This film is part of a larger series of Cretinetti comedies that addressed contemporary issues through satire

- The conscription ending reflected the reality of many young men being drafted into military service during WWI

- Leonie Laporte, who played the bride, was Deed's real-life wife and frequent co-star

- The film's title in Italian was 'La Paura dei dirigibili' and in French 'La Peur des zeppelins'

- Itala Film, one of the production companies, was one of Italy's most prestigious early film studios

- The film was distributed internationally, reflecting the global popularity of early comedy series

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of the film in Italian film trade publications praised its timely humor and André Deed's masterful physical comedy. Critics noted how effectively the film balanced the serious subject of wartime anxiety with broad slapstick elements. The film was particularly appreciated for its clever use of current events as material for comedy, with reviewers noting that Deed's literal interpretation of air raid instructions provided both laughs and social commentary. Modern film historians have recognized the film as an important example of wartime comedy and a significant entry in the Cretinetti series. Scholars of early cinema have pointed to the film as evidence of how quickly filmmakers responded to current events, creating content that was both entertaining and relevant to contemporary audiences. The film is often cited in studies of WWI-era cinema as an example of how civilian experiences of the war were reflected in popular entertainment.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly well-received by wartime audiences who found both humor and catharsis in its treatment of air raid fears. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences particularly enjoyed Deed's escalating panic and the increasingly disastrous results of his safety measures. The conscription ending resonated strongly with viewers who were experiencing similar separations and disruptions in their own lives due to the war. The Cretinetti character was already extremely popular with European audiences, and this timely installment in the series likely reinforced the character's status as a relatable everyman figure. The film's blend of physical comedy with contemporary concerns made it particularly effective with working-class audiences who were most affected by wartime disruptions. Audience reactions to the house destruction sequence were reportedly enthusiastic, as this type of elaborate physical comedy was a major draw for early cinema patrons.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Cretinetti films by André Deed

- French comedy traditions of the Pathé and Gaumont studios

- Italian commedia dell'arte traditions

- Max Linder's comedy style

- Physical comedy traditions of music hall and vaudeville

This Film Influenced

- Later Cretinetti/Boireau films

- Wartime comedy films of the 1910s and 1920s

- Charlie Chaplin's wartime-themed comedies

- Buster Keaton's disaster comedies

- Harold Lloyd's anxiety-driven comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Like many films from this era, 'The Fear of Zeppelins' is considered partially lost or surviving only in fragments. The nitrate film stock used in 1915 was highly unstable, and many films from this period have deteriorated or been lost entirely. Some sources suggest that fragments or stills from the film may exist in European film archives, particularly in Italy's Cineteca Nazionale or the French Cinémathèque Française. The Cretinetti series as a whole has suffered significant losses over time, though some entries have been preserved or partially reconstructed. Film historians continue to search for surviving copies in private collections and lesser-known archives. The film's preservation status reflects the broader challenge of maintaining early cinema heritage, with estimates suggesting that up to 90% of silent films may be lost.