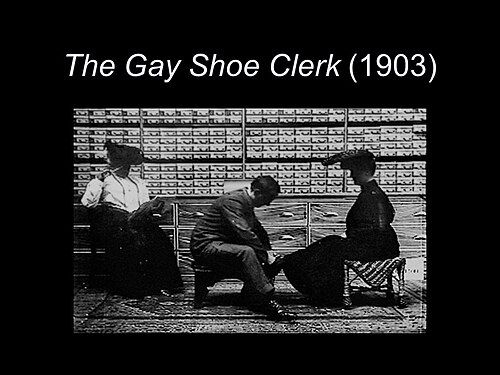

The Gay Shoe Clerk

Plot

In this early Edison comedy short, a young woman enters a shoe store to be fitted for new shoes. As the attentive shoe clerk assists her, she provocatively raises her skirt to expose her ankle, which was considered quite risqué for the time. The clerk becomes visibly excited by this glimpse of the woman's ankle and impulsively leans in to kiss her. Just as he does so, the woman's chaperone, who had been waiting nearby, strikes the clerk on the head with her umbrella as punishment for his inappropriate behavior. The clerk recoils in pain while the women exit the shop, leaving him to contemplate his foolish actions.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was shot on the Edison 'Black Maria' studio's successor indoor stage. The production utilized a single camera setup with minimal sets, typical of early cinema. The film was made during Porter's most prolific period at Edison, when he was experimenting with narrative storytelling techniques. The shoe store set was deliberately kept simple to focus attention on the actors' performances and the central action.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history when filmmakers were transitioning from simple actualities to narrative storytelling. 1903 was the same year Porter made his landmark film 'The Great Train Robbery,' which demonstrated the commercial potential of narrative cinema. The film reflects the changing social mores of the early 20th century, when Victorian values were beginning to be questioned in urban environments. The rise of nickelodeons and motion picture theaters created a demand for short, entertaining films that could attract working-class audiences. This period also saw the beginning of film censorship movements, particularly in response to content that was deemed morally questionable.

Why This Film Matters

The Gay Shoe Clerk represents an important early example of cinema's ability to push social boundaries and explore themes of sexuality and romance. The film's use of the exposed ankle as a central plot device demonstrates how early filmmakers worked within strict social constraints while still trying to create provocative content. It helped establish the romantic comedy genre in American cinema and showed that even in one-minute films, character relationships and sexual tension could be effectively portrayed. The film also illustrates the role of cinema in reflecting and sometimes challenging the social norms of the Progressive Era. Its survival provides valuable insight into early 20th century American attitudes toward gender, sexuality, and courtship.

Making Of

The film was made during a period when Edwin S. Porter was establishing himself as Edison's principal director and innovator. Porter was experimenting with narrative storytelling beyond the simple actualities that dominated early cinema. The casting of Edward Boulden was typical of Edison's practice of using regular studio actors rather than theatrical stars. The film was shot in a single take with minimal editing, as was common for the era. The production team had to be careful with the suggestive content to avoid censorship issues that were beginning to emerge in some cities. The umbrella prop was chosen specifically as it was a common accessory for respectable women of the period and symbolized moral authority.

Visual Style

The film employs the standard stationary camera technique of the era, with the camera positioned to capture the entire action in a single wide shot. The lighting is typical of early studio productions, using natural light from above or basic artificial illumination. The composition places the three characters in a triangular arrangement that emphasizes their relationships and the central conflict. The visual storytelling relies entirely on the actors' gestures and movements, as intertitles were not commonly used in such short films. The simple set design focuses attention on the characters and their interactions.

Innovations

While not technically innovative like some of Porter's other work, the film demonstrates effective use of the limited cinematic tools available in 1903. Porter shows skill in staging action for the camera and using actors' performances to convey narrative clearly without dialogue. The film's success in telling a complete story with a beginning, middle, and end in just one minute was notable for the period. Porter's experience in editing and camera work is evident in the efficient visual storytelling. The film represents the refinement of narrative techniques that Porter would perfect in his more famous works of the same year.

Music

As with all films of this era, The Gay Shoe Clerk was originally silent and would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition. Typical accompaniment might have included popular songs of the period, light classical pieces, or improvisation by a house pianist. The music would have been chosen to match the film's light, comedic tone. Some exhibitors might have used sound effects, such as a thud when the umbrella strikes the clerk, to enhance the comedy. The Edison company sometimes provided suggested musical cues with their films, though specific recommendations for this title have not survived.

Memorable Scenes

- The central moment when the woman raises her skirt to expose her ankle to the shoe clerk, creating a scandalous yet pivotal moment in early cinema that pushed the boundaries of acceptable on-screen content

Did You Know?

- This film was considered quite scandalous for its time due to the glimpse of the woman's ankle, which was taboo in Victorian society

- The film was one of the earliest examples of cinema using sexual suggestiveness as a comedic device

- Edwin S. Porter was one of the most important early American filmmakers, known for 'The Great Train Robbery' (1903)

- The film's title uses 'gay' in its original meaning of 'carefree' or 'joyful,' not the modern connotation

- This was one of many short comedies Porter made for Edison focusing on romantic or mildly suggestive situations

- The film was part of Edison's strategy to produce content that would appeal to urban, working-class audiences

- Only one copy of the film is known to survive, preserved at the Museum of Modern Art

- The film was originally sold to exhibitors for $10.57 per copy, Edison's standard price for one-minute films

- The chaperone character was a common trope in early films, representing Victorian moral authority

- This film helped establish the 'shop girl' genre that would become popular in the 1910s and 1920s

What Critics Said

Contemporary trade publications like The Edison Kinetogram and The Moving Picture World noted the film's popularity with audiences, though they were careful to describe it in genteel terms. Critics of the era praised the film's clear storytelling and effective use of comedy within its brief runtime. Modern film historians recognize the film as an important example of early narrative cinema and Porter's developing skills as a director. The film is often cited in studies of early cinema's treatment of sexuality and gender roles. Contemporary scholars view it as a fascinating document of Victorian-era attitudes toward propriety and romance.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly very popular with early nickelodeon audiences, who enjoyed its combination of mild scandal and humor. The suggestive nature of the ankle exposure made it a talking point among viewers, contributing to its commercial success. Working-class audiences in particular seemed to appreciate films that pushed social boundaries, even slightly. The film's clear visual storytelling made it accessible to the diverse immigrant audiences who frequented early motion picture theaters. Its popularity helped demonstrate to producers that there was a market for films with romantic and slightly risqué content.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French comedy shorts of the period

- Stage comedy traditions

- Vaudeville sketches

- Earlier Edison comedies

This Film Influenced

- Other Edison romantic comedies

- Early shop girl films

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedies

- Romantic comedy shorts of the 1910s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and has been included in various early cinema collections. A 35mm print exists and has been digitized for archival purposes. The film is considered to be in good condition for its age, though some deterioration is evident. It has been included in DVD collections of early Edison films and Porter's work.