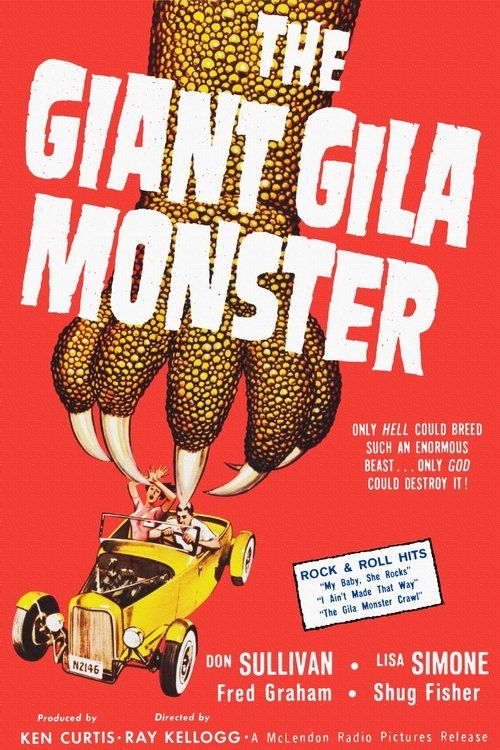

The Giant Gila Monster

"It's 40 feet long... it crawls... it kills... it's the GIANT GILA MONSTER!"

Plot

In the rural Texas community of Cactus Flats, a series of mysterious disappearances and vehicle wrecks plague the local highways. The culprit is revealed to be a fifty-foot-long gila monster that has mutated to enormous size, likely due to atomic radiation. The creature begins systematically attacking motorists, derailing a train, and eventually threatening the town itself. Chase Winstead, a resourceful young mechanic who moonlights as a rock and roll singer, takes it upon himself to stop the monster before it reaches the town's annual community dance and destroys everything. Using his mechanical skills and quick thinking, Chase devises a plan to destroy the giant reptile and save his community from certain doom.

About the Production

Filmed in just 12 days on a shoestring budget, the production used a real gila monster for close-up shots and a full-scale puppet for wider scenes. The giant monster was created using a combination of forced perspective photography and a large puppet operated by several crew members. The film was shot back-to-back with 'The Killer Shrews' using many of the same cast and crew members.

Historical Background

Released in 1959, 'The Giant Gila Monster' emerged during the golden age of American science fiction and monster movies, a period heavily influenced by Cold War anxieties about nuclear radiation and atomic testing. The late 1950s saw an explosion of 'giant creature' films following the success of 'Them!' (1954) and 'The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms' (1953). This era also witnessed the rise of drive-in theaters as a primary venue for teenage moviegoers, leading to films specifically tailored for this audience. The film reflects the concurrent rock and roll craze, incorporating musical performances as a draw for young viewers. Additionally, it represents the regional film production boom, with Texas-based producers creating content for local theaters while competing with Hollywood studios.

Why This Film Matters

While not a critical success, 'The Giant Gila Monster' has become a cult classic representative of 1950s creature features and B-movie filmmaking. The film exemplifies the era's fascination with radiation-mutated monsters, serving as a time capsule of post-atomic age anxieties. Its later appearance on Mystery Science Theater 3000 introduced it to new generations, cementing its status as a 'so bad it's good' masterpiece. The movie is frequently cited in discussions of 1950s monster cinema and serves as a textbook example of low-budget filmmaking techniques of the period. Its blend of horror, science fiction, and teen musical elements reflects the unique genre combinations that characterized late-1950s exploitation cinema.

Making Of

The production was a quintessential example of late-1950s B-movie filmmaking, created specifically for the drive-in theater circuit. Producer Gordon McLendon, who owned a chain of drive-ins, wanted content that would appeal to teenage audiences. The film was shot in Texas to take advantage of tax incentives and local landscapes. Director Ray Kellogg, a veteran of Disney's special effects department, brought technical expertise despite the limited budget. The monster effects were achieved through creative use of forced perspective, miniatures, and a large puppet that required multiple operators. The cast and crew worked grueling 12-hour days to complete filming in under two weeks. Don Sullivan, the lead actor, was also a talented musician and incorporated his musical performances into the film, a common practice in teen-oriented movies of the era.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Wilfred M. Cline, utilized creative techniques to overcome budget limitations. The film was shot in CinemaScope, though many theaters showed it in cropped formats. Forced perspective photography was extensively used to create the illusion of size for the monster, placing it in the foreground with miniature backgrounds. The Texas landscape provided natural, atmospheric settings that required minimal set construction. Night scenes were often filmed day-for-night using filters, a common cost-saving measure of the era. The train derailment sequence used sophisticated miniature photography that was quite impressive for the budget level, with careful camera angles and editing creating convincing destruction sequences.

Innovations

While not technically groundbreaking, the film showcased impressive creativity within its budget constraints. The monster effects, combining a real lizard for close-ups with a large puppet for wider shots, demonstrated resourceful problem-solving. The forced perspective techniques used to create the illusion of scale were particularly effective for the budget level. The miniature work in the train derailment scene was notably accomplished, with careful attention to scale and movement. The film's use of CinemaScope on such a limited budget was ambitious, though the format's requirements sometimes strained the production's resources. The sound design, particularly in creating the monster's vocalizations, showed innovation in combining various audio sources to create a convincing creature presence.

Music

The musical score was composed by Jack Marshall, who created a tense, dramatic soundtrack that effectively heightened the monster scenes. Notably, the film features several musical performances by star Don Sullivan, including the original songs 'Laugh, Children, Laugh' and 'My Love Is Yours.' These rock and roll numbers were inserted to appeal to teenage audiences and were typical of the hybrid genre films of the period. The soundtrack also included stock music cues from various libraries, a common practice in low-budget productions. The monster's distinctive roar was created through sound manipulation, combining animal sounds with electronic effects. The overall musical approach blended traditional horror scoring with contemporary rock elements, reflecting the film's dual appeal to monster movie fans and teenage audiences.

Famous Quotes

Chase Winstead: 'I don't know what it is, but it's big and it's hungry!'

Sheriff Jeff: 'There's something out there killing people, and it's not human!'

Chase Winstead: 'Sometimes you have to stand up and fight, even when you're scared.'

Mr. Wheeler: 'This town has never seen anything like this before!'

Chase Winstead: 'If we don't stop it, there won't be anything left of Cactus Flats!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the giant gila monster first appears, blocking the highway and attacking a car full of teenagers

- The thrilling train derailment scene where the monster attacks a moving train, causing it to crash in a spectacular miniature sequence

- The climactic final battle where Chase Winstead uses nitroglycerin and his mechanical skills to destroy the monster at the community dance

- The musical performance scenes where Don Sullivan sings to the townspeople, providing moments of levity before the monster attacks

- The discovery scene where the townspeople first realize the true scale of the threat they're facing

Did You Know?

- The giant gila monster was portrayed by a Mexican beaded lizard, not an actual gila monster, due to filming regulations

- Don Sullivan performed all his own songs in the film, including 'Laugh, Children, Laugh' which became a minor hit

- The film was produced by Gordon McLendon, a Texas radio mogul who owned several drive-in theaters

- The monster's roar was created by slowing down and modifying recordings of actual animal sounds

- Director Ray Kellogg was a former special effects artist who worked on many Disney films

- The train derailment scene used miniature models and was considered quite impressive for its budget

- The film was shot in CinemaScope but often shown in standard format in smaller theaters

- Lisa Simone was the daughter of jazz musician Nina Simone, though this was not widely known at the time

- The movie was featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000 in 1993, bringing it new cult fame

- The giant monster puppet was reportedly destroyed after filming and no longer exists

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was largely negative, with most reviewers dismissing it as typical low-budget monster fare. Variety called it 'a routine monster programmer' while noting its technical limitations. The New York Times didn't bother reviewing it, as was common for B-movies of this type. Modern critics, however, have reassessed the film within its historical context, acknowledging its charm as a period piece. Film historian Bill Warren described it as 'one of the more entertaining giant monster quickies of the era.' The film's reputation has improved over time as appreciation for 1950s B-movies has grown, with many critics now recognizing its earnest entertainment value despite its technical shortcomings.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was moderate, with the film finding its primary audience at drive-in theaters where it played as part of double features. Teenage viewers, the target demographic, generally enjoyed the combination of monster action and musical performances. The film developed a stronger following in later years, particularly after its television debut and especially following its MST3K appearance. Modern audiences often watch it as a camp classic, appreciating its nostalgic value and unintentional humor. The film maintains a steady presence at revival screenings and film festivals celebrating 1950s cinema, where it's typically received with enthusiasm by fans of vintage monster movies.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Them! (1954)

- The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953)

- Godzilla (1954)

- The Giant Claw (1957)

- The Blob (1958)

This Film Influenced

- The Giant Spider (1974)

- The Giant Gila Monster (remake discussions)

- Various SyFy channel original movies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has survived in relatively good condition and exists in various formats. Original 35mm CinemaScope prints are held in private collections and film archives. The movie entered the public domain, which has led to numerous home video releases of varying quality. The best available versions come from restored prints released by specialty labels like The Film Detective and Shout! Factory. The public domain status has actually helped ensure its survival, as multiple distributors have maintained copies over the decades. No significant restoration efforts have been undertaken by major film preservation institutions, but the film remains accessible through various home media and streaming platforms.