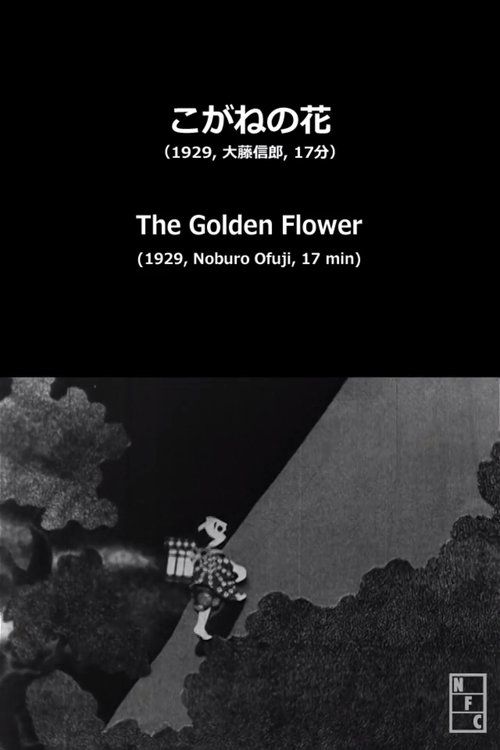

The Golden Flower

Plot

In this enchanting Japanese animated short, a weary man makes his way home from a lively village festival, taking a shortcut across a mysterious hill. As night falls, the hill transforms into a surreal landscape where reality and fantasy intertwine. He encounters a series of bizarre and magical phenomena, including dancing flowers that glow with an ethereal light and strange, otherworldly creatures. The man's journey becomes a dreamlike exploration of Japanese folklore and supernatural beliefs, culminating in a profound and mystical experience that blurs the line between the mundane and the miraculous. Upon awakening, he is left to ponder whether his adventure was real or a product of his fatigued mind.

Director

About the Production

Noburô Ôfuji created this film using cut-out animation techniques, a method he pioneered in Japanese cinema. The production involved hand-cutting paper figures and manipulating them frame by frame, a painstaking process that required immense patience and artistic skill. Ôfuji was known for his innovative use of colored paper and shadow effects, which gave his films a distinctive, theatrical quality. The film's creation coincided with a period of great artistic experimentation in Japan, as filmmakers sought to develop a unique national style of animation distinct from Western influences.

Historical Background

Created in 1959, 'The Golden Flower' emerged during a transformative period in Japanese history and cinema. Japan was in the midst of its post-war economic miracle, experiencing rapid modernization and Westernization while simultaneously striving to preserve cultural traditions. This tension between old and new is reflected in Ôfuji's work, which uses traditional techniques and themes to create something entirely modern. The late 1950s also saw the rise of Japanese cinema on the international stage, with directors like Akira Kurosawa gaining global recognition. Ôfuji's animation represented an important counterpoint to the live-action films dominating Japanese cinema, showcasing the artistic potential of animation as a medium for serious artistic expression. The film was created just as television was beginning to challenge cinema's dominance, making it part of the last generation of films created primarily for theatrical exhibition.

Why This Film Matters

'The Golden Flower' holds immense cultural significance as a masterpiece of Japanese animation that bridges traditional arts and modern cinema. The film demonstrates how ancient Japanese storytelling techniques and visual aesthetics could be adapted to the new medium of animation. Ôfuji's work has been credited with preserving traditional Japanese art forms and folklore that might otherwise have been lost to modernization. The film's international recognition helped establish Japanese animation as a legitimate art form on the global stage, paving the way for later anime creators. Today, it is studied by animation scholars worldwide as an example of how cultural specificity can create universal appeal. The film has also influenced contemporary Japanese animators who seek to incorporate traditional aesthetics into modern digital techniques.

Making Of

The creation of 'The Golden Flower' represents the culmination of Noburô Ôfuji's lifelong dedication to the art of paper animation. Working in his modest Tokyo apartment, Ôfuji would spend countless hours meticulously cutting paper figures with surgical precision. His wife often assisted by holding the paper steady during the cutting process. The animation was filmed using a custom-built rostrum camera that Ôfuji designed himself, allowing for the complex movements and layered effects that characterize his work. The film's production was particularly challenging due to the delicate nature of the paper materials, which would sometimes tear or warp under the hot studio lights. Ôfuji developed special techniques to preserve the paper, including storing it in climate-controlled conditions between shooting sessions. The soundtrack was created later, with Ôfuji carefully selecting traditional Japanese musical pieces to complement the visual narrative.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Golden Flower' is characterized by its innovative use of depth and shadow through paper cut-outs. Ôfuji employed a multi-layered approach, placing different paper elements at varying distances from the camera to create a sense of three-dimensional space. The lighting techniques were particularly sophisticated, with Ôfuji using colored gels and carefully positioned lights to create dramatic shadows and glowing effects. The camera movements were smooth and deliberate, often panning slowly across the paper landscapes to reveal new details. The film's visual composition draws heavily from traditional Japanese theater, particularly kabuki and bunraku puppet theater, in its use of flat, decorative backgrounds and stylized character movements. The color palette was meticulously chosen to evoke the seasonal changes and supernatural elements central to the story.

Innovations

Noburô Ôfuji's 'The Golden Flower' represents several significant technical achievements in animation history. The film pioneered the use of colored paper cut-outs in animation, a technique that Ôfuji refined over decades of experimentation. The multi-plane camera setup Ôfuji developed allowed for unprecedented depth and movement in paper animation. The film's lighting techniques, which created the illusion of glowing flowers and supernatural phenomena, were particularly innovative for the time. Ôfuji also developed special methods for preserving and animating delicate paper materials under hot studio lights. The seamless integration of traditional Japanese art forms with cinematic techniques demonstrated animation's potential as a medium for cultural expression. The film's success in international festivals helped establish paper animation as a legitimate artistic technique alongside cel animation.

Music

The soundtrack of 'The Golden Flower' features traditional Japanese musical instruments, including the shakuhachi bamboo flute, koto string instrument, and taiko drums. The music was composed by Seiichi Karashima, who collaborated frequently with Ôfuji on his later works. The score alternates between meditative, atmospheric passages during the man's journey and more dynamic, rhythmic pieces during the supernatural encounters. Sound effects were created using traditional methods, including wooden blocks for footsteps and bells for magical elements. The absence of dialogue in the film makes the musical score particularly important in conveying emotion and narrative progression. The soundtrack was recorded using monaural technology, typical for Japanese films of this period, but Ôfuji's careful mixing created a rich, immersive audio experience that complemented the visual poetry of the animation.

Famous Quotes

The hill remembers what the village forgets

In the space between steps, magic dances

Every flower holds a story, but only some glow with truth

Memorable Scenes

- The mesmerizing sequence where the golden flowers begin to glow and pulse with light, transforming the dark hill into a magical garden that seems to breathe with life. The scene uses Ôfuji's signature paper animation to create an otherworldly atmosphere as the flowers sway and change colors, accompanied by ethereal music and subtle sound effects.

Did You Know?

- Noburô Ôfuji was one of Japan's earliest and most influential animation pioneers, often called the 'father of Japanese animation'

- The film uses a special technique called 'chiyogami' animation, which involves traditional Japanese paper

- Ôfuji created this film without any dialogue, relying entirely on visual storytelling

- The golden flower motif is inspired by traditional Japanese folklore about supernatural plants

- This was one of Ôfuji's later works, created when he was already an established master of animation

- The film was originally intended to be shown as part of a double feature with live-action films

- Ôfuji's animation studio was actually his small apartment in Tokyo

- The film's color palette was carefully chosen to evoke traditional Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints

- Despite its short length, the film took over six months to complete

- Ôfuji often performed all aspects of production himself, from storyboarding to animation to editing

What Critics Said

Upon its release, 'The Golden Flower' was praised by critics for its innovative technique and poetic visual language. Japanese critics hailed it as a triumph of national cinema, celebrating how Ôfuji had transformed traditional paper art into a modern cinematic experience. International critics at the Venice Film Festival were particularly impressed by the film's unique aesthetic, with many noting how it differed from Western animation traditions. Contemporary critics now view the film as a landmark work that demonstrates animation's potential as a serious art form. The film has been the subject of numerous academic papers and retrospectives, with scholars analyzing its fusion of traditional Japanese aesthetics with cinematic innovation. Modern critics often cite it as an early example of how animation can convey complex emotions and ideas without dialogue.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1959 Japan were captivated by 'The Golden Flower's' magical qualities and familiar cultural references. The film's dreamlike narrative resonated with viewers who grew up with similar folktales. Many reported feeling a sense of nostalgia and cultural pride while watching the film. International audiences, particularly at film festivals, were fascinated by the unfamiliar visual style and storytelling approach. The film developed a cult following among animation enthusiasts and art film lovers in subsequent decades. Today, the film is frequently screened at animation festivals and museum retrospectives, where it continues to mesmerize audiences with its timeless beauty and technical mastery. Modern viewers often express surprise at how contemporary the film feels despite its age and traditional techniques.

Awards & Recognition

- Mainichi Film Concours - Best Animation Film (1959)

- Venice International Film Festival - Special Mention (1959)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Japanese Folktales

- Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints

- Kabuki Theater

- Bunraku Puppet Theater

- Chinese Shadow Puppetry

- Early Disney Silly Symphonies

This Film Influenced

- The Tale of the Princess Kaguya

- The Little Prince

- The Red Turtle

- Kubo and the Two Strings

- The Secret World of Arrietty

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the National Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. A restored version was created in 2005 using original negatives and materials. The restoration process involved digital cleaning and color correction while preserving the original paper texture aesthetic. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition with complete elements available.