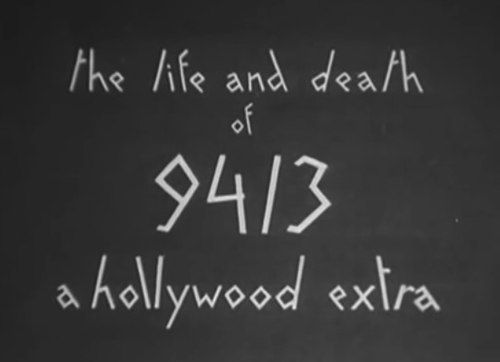

The Life and Death of 9413: A Hollywood Extra

"A story of Hollywood's cruelty, told in shadows and light"

Plot

A young man with dreams of stardom arrives in Hollywood full of hope and ambition, but quickly discovers the harsh reality of the film industry. He becomes just another anonymous extra, identified only by the number 9413 stamped on his forehead, symbolizing his complete loss of identity in the studio system. As he struggles to find meaningful work and recognition, he witnesses the cruelty and indifference of Hollywood executives who treat actors as disposable commodities. The film follows his gradual descent into despair, poverty, and madness as his dreams are systematically crushed by the dehumanizing machinery of the entertainment industry. In a powerful final sequence, 9413 meets a tragic end, becoming another forgotten victim of Hollywood's relentless appetite for fresh talent.

Director

About the Production

Filmed over weekends with borrowed equipment and volunteer crew members. The distinctive number 9413 was actually painted on the actor's forehead for each take. Many scenes were shot in real Hollywood casting offices and studio corridors to maintain authenticity. The film's experimental visual style was achieved through creative use of shadows, mirrors, and camera angles rather than expensive special effects.

Historical Background

Created in 1928, during the tumultuous transition from silent to sound films, this experimental work emerged at a time when Hollywood's studio system was at its peak power but also facing growing criticism. The late 1920s saw the rise of labor movements in Hollywood, with actors and crew members demanding better working conditions and recognition. This film directly addressed the dehumanizing treatment of performers in an industry that was rapidly industrializing. The timing is particularly significant as it was made just before the 1929 stock market crash, which would dramatically alter the film industry and end the golden age of silent cinema.

Why This Film Matters

This film stands as one of the earliest and most powerful critiques of Hollywood from within the industry itself. Its experimental visual language influenced generations of filmmakers interested in using cinema as social commentary. The film's depiction of the individual crushed by industrial systems resonated beyond Hollywood, speaking to broader anxieties about modernization and loss of identity in the machine age. It helped establish the tradition of Hollywood self-criticism that would later appear in films like 'Sunset Boulevard' and 'The Player'. The number 9413 has become a cultural reference for anonymity and dehumanization in mass media.

Making Of

Robert Florey, a French immigrant who had worked as an assistant director in Hollywood, conceived this film as a response to the dehumanization he witnessed in the studio system. Working with cinematographer Gregg Toland (who would later shoot 'Citizen Kane'), Florey created a visually striking film using minimal resources. The production was essentially a guerilla filmmaking operation, with the crew sneaking into studio backlots and offices after hours. The number 9413 was applied to the actor's forehead using theatrical makeup that had to be reapplied between takes. Many of the extras in the casting scenes were actual Hollywood extras who volunteered their time, adding authenticity to the depiction of the cattle-call atmosphere.

Visual Style

Gregg Toland's cinematography was revolutionary for its time, employing dramatic shadows, distorted angles, and creative use of mirrors to convey psychological states. The film used superimposition and double exposure techniques to create surreal dream sequences. The casting office scenes were shot with wide angles to emphasize the crowded, dehumanizing environment, while close-ups of 9413 used harsh lighting to highlight his isolation. The famous descending numbers sequence was achieved through innovative camera techniques that created a sense of overwhelming pressure.

Innovations

Pioneered the use of rapid montage editing to convey the passage of time and psychological breakdown. The film's innovative use of shadows and lighting influenced film noir cinematography. It demonstrated how complex emotional narratives could be told without dialogue through visual symbolism alone. The creative use of superimposition and double exposure techniques predated similar effects in more famous films. The production proved that powerful cinema could be created with minimal resources through artistic innovation.

Music

As a silent film, it originally had no synchronized soundtrack but was accompanied by live musical performances. The score typically included dissonant, modernist compositions to match the film's experimental nature. When the film was restored in the 1990s, composer Paul Glass created a new orchestral score that blended period-appropriate music with contemporary elements. Some screenings featured improvisational jazz accompaniment, reflecting the film's avant-garde spirit.

Famous Quotes

"You are not a person. You are a number. You are 9413." - Casting Director

"In Hollywood, dreams are manufactured, and so are dreamers." - Opening intertitle

"They come here seeking immortality and find only anonymity." - Narrator

"The camera loves everyone, but the studio loves no one." - Closing intertitle

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the protagonist's name is literally erased and replaced with the number 9413

- The surreal dream sequence where giant numbers descend upon the helpless extra

- The powerful final scene where 9413's body is discovered, his number still visible on his forehead

- The cattle-call casting scene with hundreds of extras being herded like animals

- The mirror sequence showing the protagonist's multiple reflections losing their identity

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first American films to directly critique the Hollywood studio system from within

- Director Robert Florey also appears in the film as one of the cruel casting directors

- The number 9413 was chosen arbitrarily but became iconic in cinema history

- The film was made for less than $5,000 using borrowed equipment and volunteer actors

- It was initially rejected by major studios for being too critical of Hollywood

- The film's experimental style was influenced by German Expressionism and French avant-garde cinema

- Jules Raucourt, who played 9413, was actually a French actor struggling in Hollywood at the time

- The film was shot in just six days over two weekends

- It was one of the first films to use rapid montage techniques to show the passage of time

- The famous scene with the descending numbers was created using a simple animation technique

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's bold visual style and courageous subject matter, with Variety calling it 'a daring and brilliant piece of cinematic art.' The New York Times noted its 'powerful social commentary disguised as experimental cinema.' Modern critics have reevaluated it as a masterpiece of avant-garde filmmaking, with the Village Voice describing it as 'perhaps the most savage indictment of Hollywood ever captured on film.' Film scholars consider it a crucial bridge between European avant-garde cinema and American social critique in film.

What Audiences Thought

The film had limited theatrical release due to its controversial subject matter, but it developed a cult following among film enthusiasts and industry insiders. Those who saw it were deeply affected by its unflinching portrayal of Hollywood's dark side. In art house circuits, it was praised for its artistic courage and technical innovation. Modern audiences discovering it through film festivals and retrospectives often remark on how contemporary its themes remain, despite being nearly a century old.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the most significant avant-garde films of the 1920s by the National Film Preservation Board

- Selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1997

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- French avant-garde films

- Soviet montage theory

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

- Ballet Mécanique

This Film Influenced

- Sunset Boulevard

- The Bad and the Beautiful

- A Star Is Born (1937)

- The Player

- Ed Wood

- The Last Tycoon

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved by the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. Restored in 1997 using original nitrate materials. The restoration included the creation of a new musical score. Considered in excellent condition for a film of its era.