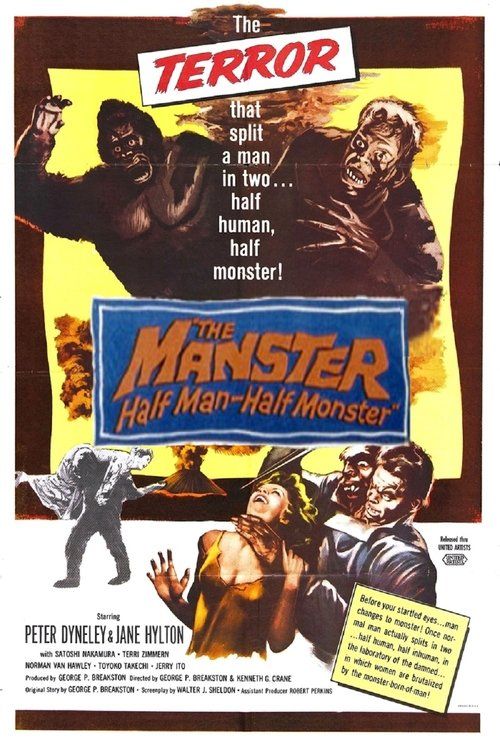

The Manster

"Half Man... Half Monster... All Terror!"

Plot

American journalist Larry Stanford, stationed in Japan, visits the remote laboratory of Dr. Robert Suzuki for what he believes is a routine interview about scientific advancements. Unbeknownst to Larry, the mad scientist injects him with an experimental serum designed to accelerate human evolution, triggering a horrifying transformation that gradually turns him into a two-headed monster. As Larry's personality becomes increasingly violent and erratic, his wife Linda grows concerned about his strange behavior and the mysterious disappearances occurring around them. The transformation culminates in Larry developing a savage second head with its own consciousness, creating a split personality struggle between his human and monstrous sides. Dr. Suzuki's true intentions are revealed as part of a larger scheme to create a superior race, leading to a climactic confrontation in the laboratory where Larry's monstrous nature is fully unleashed.

About the Production

This was one of the first American-Japanese co-productions in the horror genre, filmed during a 12-day shooting schedule. The production faced significant challenges due to language barriers between American and Japanese crew members. The two-headed monster effect was achieved using a combination of makeup prosthetics, split-screen photography, and a body double rather than sophisticated special effects. The film was shot in authentic Japanese locations, including actual research facilities, to enhance its atmosphere and authenticity.

Historical Background

The Manster emerged during a fascinating period of post-war cultural exchange between Japan and the United States, reflecting the growing collaboration between the two countries' entertainment industries. The late 1950s saw increased American interest in Japanese culture, while Japan was rebuilding its film industry after World War II and establishing itself as a major force in international cinema. This co-production was particularly significant as it came during the golden age of science fiction horror, when atomic age anxieties about radiation, scientific experimentation, and the potential dangers of unchecked technological advancement were prevalent in popular culture. Japan's own traumatic experiences with atomic bombs made themes of scientific hubris and mutation particularly resonant, while American audiences were captivated by stories of scientific experiments gone wrong in the Cold War era. The film also reflected contemporary fears about loss of identity and the unknown consequences of tampering with nature, themes that resonated strongly in both Eastern and Western cultures.

Why This Film Matters

The Manster holds a unique place in cinema history as a pioneering example of successful American-Japanese horror co-production, creating a template for future international collaborations in the genre. The film's blend of Japanese and American horror tropes established a cross-cultural cinematic language that would influence numerous subsequent productions. Its portrayal of a Westerner undergoing physical and psychological transformation in Japan touched on complex themes of cultural identity, assimilation, and the fear of the 'other' that were particularly relevant during the Cold War era. The movie's exploration of scientific hubris and its consequences resonated with audiences still grappling with the atomic age and its implications. Over the decades, the film has developed a significant cult following, with horror enthusiasts appreciating its earnest approach to monster movie conventions and its important role in the evolution of body horror cinema. Its public domain status has ensured wide distribution and accessibility, contributing to its enduring legacy as a cult classic.

Making Of

The production of 'The Manster' was a complex cross-cultural endeavor that required navigating significant language and cultural barriers between the American and Japanese crew members. Director George P. Breakston, who had extensive experience making films in Japan, served as a crucial bridge between the two production teams. The makeup effects for the two-headed monster were particularly challenging, requiring hours of application each day in Japan's humid summer conditions. The cast and crew often worked 16-hour days to complete the film within its tight 12-day shooting schedule. The script underwent multiple revisions to satisfy both American and Japanese sensibilities, resulting in a unique blend of Western horror conventions and Eastern philosophical elements. The film's success in international markets led to several similar co-productions in the early 1960s, establishing a template for cross-cultural horror filmmaking.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Akira Mimura effectively utilized the Japanese locations to create an atmospheric backdrop that elevated the film beyond typical B-movie fare. The use of Tokyo's urban landscape and traditional Japanese settings provided a visual contrast between modernity and tradition that mirrored the film's themes of transformation and cultural conflict. The camera work during the transformation sequences employed innovative techniques for the time, including dissolves, superimpositions, and split-screen effects to create the illusion of Larry's changing physical state. The film's black and white photography enhanced the horror elements, with deep shadows and high contrast lighting creating a sense of dread and unease throughout. The cinematography successfully blended Japanese cinematic sensibilities with American horror conventions, creating a unique visual style that contributed to the film's cross-cultural appeal and its effectiveness as a monster movie.

Innovations

For its limited budget, The Manster achieved several notable technical feats, particularly in its creation of the two-headed monster effect. The film's makeup effects, while crude by modern standards, were innovative for their time, using a combination of prosthetics, camera tricks, and strategic editing to create the illusion of physical transformation. The split-screen techniques used to show both heads simultaneously were particularly effective given the film's limited resources, requiring precise timing and execution during filming. The production also pioneered certain approaches to international co-production, establishing workflows and communication methods that would be used in later collaborations between American and Japanese film industries. The film's successful integration of location shooting in Japan with studio work demonstrated new possibilities for international filmmaking, particularly in the horror genre. The sound recording techniques used to create the monster's distinctive voice were also innovative for the era, combining multiple audio tracks to achieve the desired effect.

Music

The film's score was composed by Sei Ikeno, who skillfully blended traditional Japanese musical elements with Western horror film conventions to create a unique atmospheric soundscape. The soundtrack featured eerie string arrangements and percussive elements that heightened the tension during key scenes, particularly the transformation sequences and the climactic laboratory confrontation. The music effectively complemented the film's cross-cultural nature, using both Western orchestral techniques and Japanese musical motifs to reinforce its international character. The sound design was particularly effective in creating the monster's unsettling presence, with distorted vocal effects and animalistic sounds contributing to the creature's terrifying nature. While the score was never commercially released as a standalone album, it has been praised by cult film enthusiasts for its atmospheric qualities and its role in establishing the film's distinctive tone and mood.

Famous Quotes

Something is happening to me... something terrible! - Larry Stanford

Science must advance, no matter the cost! - Dr. Suzuki

You're not the man I married anymore! - Linda Stanford

Two heads are better than one... especially when one is a monster! - Dr. Suzuki

The serum is working... better than I could have imagined! - Dr. Suzuki

I feel... different. Stronger. But something's wrong inside me. - Larry Stanford

Memorable Scenes

- The first transformation sequence where Larry begins to change, shown through disturbing dissolves and makeup effects that shocked 1959 audiences

- The dramatic reveal of the fully formed two-headed monster, achieved through clever split-screen photography and editing

- The climactic laboratory scene where the monster runs rampant, combining horror and action in classic B-movie fashion

- The emotional confrontation between Linda and the transformed Larry, providing genuine pathos amid the horror elements

- The opening sequence in Dr. Suzuki's mysterious laboratory, establishing the film's atmosphere of scientific dread

Did You Know?

- The film's original title was 'The Split' but was changed to 'The Manster' for marketing purposes, combining 'man' and 'monster'

- The two-headed effect was created using a split-screen technique and required Peter Dyneley to wear extremely heavy prosthetic makeup for up to 8 hours per day

- This was one of the earliest American-Japanese horror co-productions, paving the way for future international collaborations

- The film was shot in just 12 days, an incredibly short schedule even for B-movie standards of the era

- Tetsu Nakamura was a famous actor in Japan but this was one of his few English-language film roles

- The movie was featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000 in 1992, introducing it to a new generation of cult film fans

- The film fell into the public domain, which has ironically helped ensure its survival through multiple releases

- Dr. Suzuki's laboratory scenes were filmed in an actual Japanese medical research facility

- The second head was played by different actors in various scenes to achieve the desired effect

- The film was banned in several countries upon release due to its graphic content and themes of scientific horror

- Peter Dyneley performed most of his own stunts despite the challenging makeup and physical transformation requirements

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release in 1959, The Manster received mixed reviews from mainstream critics. The New York Times dismissed it as 'routine monster movie fare' while noting its 'novel setting and unusual premise.' Variety acknowledged the film's ambitious scope but criticized its low-budget special effects and occasionally melodramatic performances. However, some genre publications of the era praised its effective use of Japanese locations and its straightforward approach to monster movie conventions. Over time, critical reassessment has become more favorable, with modern film historians recognizing the movie's historical significance as an early international co-production and its place in the evolution of cross-cultural horror cinema. Contemporary critics often appreciate the film's atmospheric qualities, its earnest approach to the transformation sequences, and its role in bridging Eastern and Western horror traditions. The film is now frequently cited in studies of 1950s B-movies and international horror co-productions.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audiences, particularly drive-in theater goers and grindhouse patrons, responded positively to The Manster, finding its blend of horror elements and exotic Japanese setting appealing and distinctive. The film developed a strong cult following over the decades, especially after being featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000 in 1992, which introduced it to a new generation of viewers. Horror enthusiasts have come to appreciate the film's straightforward approach to monster movie conventions and its surprisingly effective moments of tension despite its low-budget limitations. The movie's brief runtime and direct storytelling have made it a favorite among fans of 1950s B-movies who value its efficiency and lack of pretension. Modern audiences often discover the film through its reputation as a 'so bad it's good' classic, though many find genuine merit in its atmospheric elements, committed performances, and its historical significance as an early international horror co-production.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) - theme of dual personality and transformation

- The Fly (1958) - scientific experimentation gone wrong

- Godzilla (1954) - Japanese monster movie conventions and themes of mutation

- The Thing from Another World (1951) - scientific horror in isolated settings

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) - themes of loss of identity and transformation

This Film Influenced

- The Brain That Wouldn't Die (1962) - similar themes of scientific experimentation and body horror

- The Green Slime (1968) - American-Japanese science fiction horror co-production

- The Incredible Two-Headed Transplant (1971) - direct exploitation of the two-headed monster concept

- The Man with Two Heads (1972) - similar premise of dual-headed creature

- Various body horror films of the 1970s and 1980s that explored themes of physical transformation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has survived through various home video releases and is currently in the public domain. While the original camera negative appears to have been lost, decent quality prints exist through various distribution channels. Multiple restoration efforts have been undertaken by cult film distributors, resulting in varying quality versions available on different platforms. The film's public domain status has actually helped ensure its survival through numerous releases by different companies over the decades. Several specialty labels have released restored versions on DVD and Blu-ray, often sourced from the best available 35mm prints.