The Mechanical Man

Plot

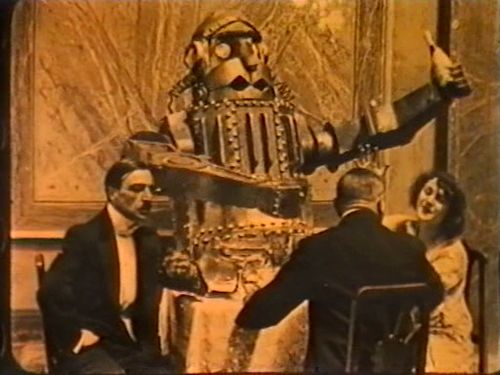

A brilliant scientist creates a revolutionary mechanical man, a humanoid robot with superhuman speed and strength that can be controlled remotely. Before he can reveal his invention to the world, the scientist is murdered by a criminal gang led by the cunning Mado, who desperately wants the blueprints for the mechanical man. The criminals are initially captured and sentenced, but Mado escapes from prison and kidnaps the scientist's niece, forcing her to reveal the construction plans. Using these stolen instructions, Mado builds her own mechanical man for criminal purposes, leading to an epic confrontation between the two robots in the streets of the city. The film culminates in a spectacular battle between the mechanical creations, showcasing early special effects and establishing themes of technology's dual potential for both good and evil.

About the Production

The film featured groundbreaking special effects for its time, including miniatures, stop-motion techniques, and elaborate mechanical costumes. The robot costumes were reportedly extremely heavy and cumbersome, requiring actors to take frequent breaks. The production faced significant challenges with the mechanical props, which frequently broke down during filming. Director André Deed, who also starred in the film, drew on his background in physical comedy to choreograph the robot movements.

Historical Background

The Mechanical Man emerged during a fascinating period in Italian cinema history, following World War I when the Italian film industry was attempting to reassert itself on the international stage. The early 1920s saw Italian filmmakers experimenting with new genres and technologies, moving away from the historical epics that had dominated the pre-war period. This film reflected contemporary anxieties about industrialization and automation, as society grappled with the increasing mechanization of daily life. The post-war period also saw significant advances in electrical engineering and robotics theory, making the concept of a mechanical man particularly relevant to 1921 audiences. Italy was experiencing rapid industrial growth, particularly in the northern cities where the film was produced, and this technological optimism mixed with fear found perfect expression in the film's dual portrayal of the mechanical man as both protector and potential threat.

Why This Film Matters

'The Mechanical Man' holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the earliest examples of the robot in film, predating more famous works like 'Metropolis' (1927) and 'Frankenstein' (1931). The film established several tropes that would become staples of science fiction cinema: the rogue scientist, the stolen technology falling into criminal hands, and the ultimate battle between good and evil machines. Its influence can be traced through decades of robot films, from the serials of the 1930s to modern blockbusters. The film also represents an important milestone in Italian cinema's contribution to the science fiction genre, demonstrating that Italian filmmakers were not just masters of historical epics but also pioneers in technological storytelling. The surviving fragment continues to be studied by film historians as a crucial link in the evolution of cinematic special effects and the development of the robot as a cultural icon.

Making Of

The production of 'The Mechanical Man' was an ambitious undertaking for Italian cinema in 1921, pushing the boundaries of special effects and technical innovation. The mechanical man costumes were engineering marvels of their time, constructed from metal, wood, and leather with intricate joint mechanisms. Actors inside the suits had to endure extreme conditions, with temperatures reaching dangerous levels during filming under studio lights. Director André Deed, drawing from his extensive experience in physical comedy, insisted on performing his own stunts, including several dangerous sequences with the heavy mechanical props. The film's most complex sequence - the battle between two mechanical men - required weeks of preparation and involved multiple camera techniques including double exposure and matte shots. The production team built detailed miniature models of city blocks for the destruction sequences, which were then combined with full-size footage to create convincing scale. Despite the technical challenges, the film was completed on schedule, though at significant cost to the production company.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Umberto Scalabrini was innovative for its time, employing multiple camera techniques to create the illusion of giant mechanical men moving through city streets. The film utilized forced perspective photography, combining full-size props with carefully positioned actors to achieve convincing scale. Dynamic camera movements, including tracking shots that followed the mechanical men's rampage through the city, were particularly advanced for 1921. The battle sequence featured complex editing patterns and multiple angles, creating a sense of action and movement that was rare in early cinema. The film also made effective use of lighting to create dramatic shadows and highlights on the metallic surfaces of the mechanical man costumes.

Innovations

The film featured several groundbreaking technical achievements for 1921, including some of the earliest uses of miniatures and scale models to create the illusion of destruction in urban environments. The mechanical man costumes themselves were engineering marvels, featuring working joints and movable parts that allowed for surprisingly fluid movement. The production pioneered techniques for combining live action with special effects, using multiple exposure photography to place the mechanical characters in the same frame as human actors. The film's most significant technical achievement was the battle sequence between two mechanical men, which required complex choreography, special effects, and editing techniques that were far ahead of their time. The production team also developed innovative methods for creating electrical effects and sparks to suggest the mechanical nature of the characters.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Mechanical Man' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from classical pieces and popular music of the era, with specific themes for different characters and situations. For dramatic sequences, the music would have been tense and percussive, while romantic scenes featured softer melodies. The mechanical man's appearances were likely accompanied by mechanical-sounding instruments or special effects created by the theater's organist or orchestra. Modern screenings of the surviving fragment typically feature newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the spirit of 1920s accompaniment while acknowledging the film's science fiction elements.

Famous Quotes

The machine has no heart, but it can be made to serve man's purposes - for good or for evil.

In the wrong hands, even the greatest invention becomes a weapon.

Science without conscience is but the soul's perdition.

The mechanical man knows no fear, no pain, no mercy - only the commands of its master.

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic reveal of the first mechanical man rising from the laboratory table, with sparks flying and mechanical sounds created by the orchestra

- The spectacular battle between the two mechanical men in the city streets, featuring groundbreaking special effects and miniature work

- The scientist's murder scene, which uses shadow and lighting to create tension without showing graphic violence

- Mado's escape from prison, which features innovative camera work and stunt sequences typical of the adventure serial genre

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest science fiction films to feature a robot, predating Fritz Lang's 'Metropolis' by five years

- The film was considered lost for decades until a damaged 26-minute fragment was discovered in the 1990s

- The mechanical man costume weighed over 100 pounds and had limited visibility for the actor inside

- Director André Deed was a famous French comedian who worked extensively in Italy under the name 'Cretinetti'

- The robot's design influenced later science fiction films, including the iconic look of robots in 1930s serials

- The film featured some of the most elaborate special effects of Italian cinema in the early 1920s

- Only about one-third of the original film survives today, with the remaining footage presumed lost forever

- The battle between the two mechanical men was filmed using a combination of full-size props and scale models

- The film was distributed internationally under various titles including 'L'Homme Mécanique' in France and 'Der mechanische Mann' in Germany

- Contemporary reviews praised the film's technical achievements but criticized its melodramatic plot

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1921 praised the film's technical achievements and innovative special effects, with many reviews highlighting the impressive mechanical man designs and the spectacular battle sequence. However, some critics found the plot melodramatic and predictable, typical of adventure serials of the period. Modern film historians and critics have reevaluated the film as a groundbreaking work of early science fiction, with particular appreciation for its ambitious special effects and its role in establishing robot cinema tropes. The surviving fragment has been analyzed in academic circles as an important example of early 20th century technological anxiety in popular culture. Critics today note that while the film's narrative may seem simplistic by modern standards, its visual imagination and technical innovation were remarkable for its time.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1921 was generally positive, with viewers particularly impressed by the spectacular effects sequences and the novelty of seeing mechanical men on screen. The film performed well in Italian cities and had moderate success in international markets, particularly in France and Germany where science fiction was gaining popularity. Modern audiences who have seen the surviving fragment through film festivals and archival screenings often express fascination with the film's visual style and historical significance, despite the incomplete nature of the surviving material. The film has developed a cult following among silent film enthusiasts and science fiction historians who appreciate its pioneering role in robot cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

- Karel Čapek's R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots)

- Early 20th century scientific advances

- Italian Futurist movement

- German Expressionist cinema

This Film Influenced

- Metropolis (1927)

- Frankenstein (1931)

- The Phantom Empire (1935)

- The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951)

- Westworld (1973)

- The Terminator (1984)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost. Only a 26-minute fragment survives, discovered in the 1990s in a private collection. This fragment represents approximately one-third of the original 80-minute film. The surviving material has been restored by film archives and is occasionally screened at silent film festivals and special events. The complete film is considered lost, with no known complete prints existing in any film archive worldwide. The surviving fragment has been preserved by the Cineteca Italiana and other film institutions, ensuring that at least this portion of this historically significant film will remain accessible to future generations.