The Miller and the Sweep

Plot

In this early British comedy short, a miller and a chimney sweep engage in a comical brawl outside a flour mill. The miller swings a bag of flour while the sweep retaliates with what appears to be another bag, but when it breaks open, it reveals soot instead. The two men become covered in each other's materials - the miller blackened with soot and the sweep whitened with flour. As the chaotic fight escalates, a crowd of curious spectators gathers to watch the spectacle. Eventually, the onlookers join in, chasing the flour-covered sweep and the soot-stained miller through the streets, creating a public spectacle of the two men's ridiculous appearance.

Director

About the Production

Filmed on location in Brighton using a single stationary camera. The film was shot on 35mm film using a Lumière Cinématographe camera. The entire sequence was likely filmed in one take, as was common for early films. The flour and soot effects were achieved practically, with the actors actually being covered in the materials during filming.

Historical Background

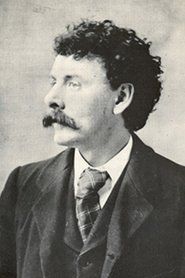

The Miller and the Sweep was produced during the pioneering era of cinema, just two years after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening in 1895. In 1897, cinema was still a novelty attraction shown in music halls, fairgrounds, and traveling exhibitions. The British film industry was in its infancy, with filmmakers like George Albert Smith, Birt Acres, and Robert W. Paul establishing the foundations of British cinema. This period saw the transition from simple actualities (films of real events) to narrative fiction films. The film reflects the Victorian era's fascination with visual spectacle and comedy, while also demonstrating the emerging language of cinema, including the use of continuity editing and narrative structure. Brighton, where the film was made, was becoming an important center for early British film production.

Why This Film Matters

The Miller and the Sweep represents an important milestone in the development of narrative cinema and comedy filmmaking. As one of the earliest examples of a structured comedy with a clear setup, conflict, and resolution, it helped establish conventions that would dominate comedy films for decades. The film's use of visual humor and physical comedy (slapstick) would influence countless future comedians and filmmakers. It also demonstrates early understanding of cinematic time and space, using a single location but creating a complete narrative arc. The film is significant for its role in the development of British cinema, showcasing the creative innovations happening outside of the more well-documented French and American early film industries. Its survival makes it an invaluable document of early cinematic techniques and storytelling approaches.

Making Of

The film was shot in Brighton, where George Albert Smith had established his film studio. Smith, who was also a hypnotist and psychic researcher, brought a unique perspective to early filmmaking. The production was typical of the era - minimal crew, natural outdoor lighting, and actors performing in real clothing. The practical effects involving flour and soot were genuinely messy for the performers, who had to be covered in these materials for the filming. Smith's wife Laura Bayley, who played the chimney sweep, was one of the earliest film actresses and regularly appeared in his productions, often in male roles due to the limited casting pool available. The film was likely shot in a single day with minimal rehearsal, as was common for these early short films.

Visual Style

The cinematography is characteristic of 1897 filmmaking, using a single stationary camera positioned to capture the entire action in one wide shot. The camera work is static and functional, typical of the era when camera movement was not yet common. The film uses natural outdoor lighting, creating a high-contrast image that emphasizes the white flour and black soot against the actors' clothing. The composition places the action centrally in the frame, ensuring all details are visible to the audience. The visual clarity of the flour and soot effects demonstrates Smith's understanding of how certain visual elements would read well on film, an important consideration in the early days of cinema.

Innovations

While not technically innovative compared to some of Smith's other works (which included early use of close-ups and special effects), The Miller and the Sweep demonstrates solid technical proficiency for its era. The film shows good understanding of continuity and spatial relationships within a single shot. The practical effects with flour and soot were executed effectively for the camera, showing Smith's grasp of what would read well visually on film. The film's clear narrative structure within its brief running time represents an achievement in early cinematic storytelling. The survival of the film itself is testament to the relatively stable film stock and processing techniques being developed by 1897.

Music

As a silent film from 1897, The Miller and the Sweep had no synchronized soundtrack. During exhibition, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra in music halls, or possibly a phonograph recording in some venues. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or selected from popular pieces of the era, chosen to match the comedic action on screen. The type of music would have varied by venue and the musician's interpretation, but would typically have been light and playful to enhance the comedy.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue - silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic moment when the sweep's bag breaks open revealing soot instead of flour, creating the visual punchline of the film and leading to both men being covered in contrasting materials - the miller in black soot and the sweep in white flour.

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest examples of a comedy film with a clear narrative structure and visual punchline

- Director George Albert Smith was a pioneer of British cinema who made over 200 films between 1897-1903

- The film was part of the early 'trick film' genre that relied on visual gags and physical comedy

- Smith was also a psychic researcher and incorporated some of his interest in visual perception into his filmmaking techniques

- The film demonstrates early use of the chase sequence, which would become a staple of comedy films

- It was distributed by the Warwick Trading Company, one of the most important early film distributors in Britain

- The miller was played by Tom Green, a regular actor in Smith's films

- The chimney sweep was played by Laura Bayley, Smith's wife, who appeared in many of his films in male roles

- The film survives today and is preserved in the BFI National Archive

- This film was made during the very early days of cinema, just two years after the first public film screenings

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception of the film is difficult to trace as film criticism was not yet established as a profession in 1897. However, the film was commercially successful enough to be widely distributed by the Warwick Trading Company. Modern film historians and critics recognize it as an important early example of narrative comedy. The British Film Institute and film scholars consider it a significant work in George Albert Smith's oeuvre and in the development of early British cinema. It is often cited in academic studies of early film comedy and the evolution of cinematic language.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by Victorian audiences who were still experiencing the novelty of moving pictures. The simple, visual humor was easily understood across language barriers, making it popular for international distribution. Audiences of the era were particularly entertained by films showing everyday situations turned chaotic, and the sight of two men covered in flour and soot would have been considered hilarious. The film's brevity (one minute) made it ideal for the short attention spans of early cinema audiences who were watching films as part of variety show programs. Its inclusion in traveling show programs suggests it was a reliable crowd-pleaser.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Early French comedies by the Lumière brothers

- Music hall comedy traditions

- Victorian theatrical comedy

This Film Influenced

- Later chase comedies

- Slapstick films of the 1900s

- Mack Sennett comedies

- The Keystone Cops films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives and is preserved in the British Film Institute National Archive. It has been restored and is available for viewing through various archival channels. The preservation status is good for a film of this age, though some deterioration typical of films from this period may be present. Digital copies have been made for conservation and access purposes.