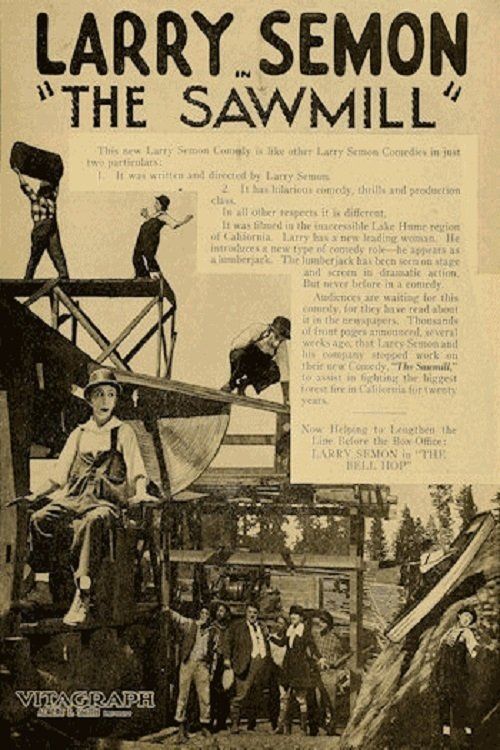

The Sawmill

"A Riot of Laughs in a Sawmill of Love!"

Plot

Larry Semon plays a clumsy but good-hearted sawmill worker who falls for the beautiful daughter of the mill owner. His romantic aspirations are constantly thwarted by the bullying foreman, portrayed by Oliver Hardy, who also has his eyes on the young woman. The film escalates into a series of chaotic slapstick sequences involving dangerous sawmill equipment, elaborate chases, and physical confrontations. Through a combination of luck and persistence, the bumbling hero ultimately wins the girl's affection while outsmarting his brutish rival. The climax features a spectacular destruction of the sawmill with Semon's character emerging victorious amidst the comedic chaos.

About the Production

The film featured elaborate and dangerous stunt work with real sawmill equipment, requiring careful coordination to ensure actor safety. Semon was known for performing his own stunts, often at great personal risk. The production utilized actual working sawmill machinery, adding authenticity but also increasing the danger factor during filming.

Historical Background

The Sawmill was produced during a transformative period in American cinema, as the film industry was consolidating in Hollywood and establishing the star system. 1922 was a year of significant growth for the motion picture business, with theaters becoming more sophisticated and audiences demanding higher quality productions. The post-World War I economic boom was in full swing, and comedies like Semon's provided escapist entertainment for a prosperous society. The industrial setting of the film reflected America's ongoing industrialization and the public's fascination with machinery and technology. Silent comedy was at its creative peak, with comedians like Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and Semon each developing distinctive styles and competing for audience attention. The film also came before the Hollywood scandals that would lead to the implementation of the Hays Code in 1934, allowing for more physical comedy and violent gags than would later be permitted.

Why This Film Matters

While not as historically significant as the works of Chaplin or Keaton, 'The Sawmill' represents an important example of the broader comedy landscape of the early 1920s. The film showcases the workplace comedy genre that was popular during this period, reflecting the industrial nature of American society and the working-class experiences of many filmgoers. Semon's style, though less enduring than some of his contemporaries, influenced the development of physical comedy and stunt work in films. The collaboration between Semon and Hardy provides early evidence of Hardy's comedic talents before his legendary partnership with Laurel. The film also demonstrates how silent comedies used everyday environments and situations to create universal humor that transcended language barriers, contributing to cinema's emergence as a truly international art form.

Making Of

The production of 'The Sawmill' exemplified Larry Semon's approach to comedy filmmaking, which emphasized elaborate physical gags and dangerous stunt work over subtle characterization. Semon, who both directed and starred in the film, was known for his hands-on approach to filmmaking, often designing his own stunts and gags. The sawmill setting provided ample opportunities for comedic peril, with real circular saws, conveyor belts, and logging equipment incorporated into the action sequences. Oliver Hardy, who would later find international fame as half of Laurel and Hardy, plays the villainous foreman with his already-developed screen presence and physical comedy skills. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for comedy shorts of the era, with minimal rehearsal and emphasis on spontaneous comedic moments. The chemistry between Semon and Hardy was evident, though their dynamic here was as adversaries rather than the friendly partners Hardy would later become known for.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of early 1920s comedies, was functional rather than artistic, focusing primarily on capturing the physical comedy and ensuring all gags were clearly visible to the audience. The camera work was relatively static compared to later films, with medium shots used to frame the physical action effectively. The industrial setting provided opportunities for interesting visual compositions, with the large machinery and moving parts creating dynamic backgrounds for the comedy. The film likely used multiple cameras for some of the more dangerous sequences to ensure adequate coverage of the stunts. The black and white photography emphasized the contrast between the characters and their industrial environment, while the lighting was designed to highlight the action rather than create mood or atmosphere.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, 'The Sawmill' demonstrated considerable skill in coordinating complex physical comedy sequences with potentially dangerous equipment. The film's use of real sawmill machinery for comedic effect required careful planning and execution to ensure safety while maintaining the appearance of chaos and danger. The destruction sequence at the film's climax was technically ambitious for its time, involving multiple gags and effects happening simultaneously. The film also showcased effective use of editing to enhance comedic timing, with cuts timed to punctuate physical gags and maintain the rapid pace of the action. The coordination between Semon's performance direction and the technical execution of the stunts represented a significant achievement in early comedy filmmaking.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Sawmill' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The typical accompaniment would have been a piano or small orchestra, with music selected to enhance the on-screen action. Comedic sequences would have been scored with lively, upbeat music, while romantic moments would have featured more melodic, tender themes. The sawmill setting might have inspired the use of mechanical or rhythmic musical motifs during the industrial sequences. Some larger theaters might have used compiled cue sheets or original compositions specifically tailored to the film. The music would have played a crucial role in establishing the film's tone and enhancing the comedic timing of the physical gags.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was limited to intertitles. Memorable title cards included: 'When love strikes, even a sawmill can't stop it!' and 'He may be clumsy, but his heart is in the right place!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Semon's character struggles with basic sawmill equipment, setting up his incompetence for comedic effect

- The elaborate chase scene through the working sawmill with characters dodging circular saws and conveyor belts

- The climactic destruction sequence where the entire sawmill collapses in a spectacular display of physical comedy and special effects

- The romantic interlude between Semon and the mill owner's daughter, providing brief respite from the chaotic action

- The confrontation scenes between Semon and Hardy's character, showcasing their contrasting physical comedy styles

Did You Know?

- This film was released during the peak of Larry Semon's popularity in the early 1920s, before his career decline later in the decade

- Oliver Hardy appears in this film before his legendary partnership with Stan Laurel began in 1927

- The sawmill set was so elaborate and dangerous that it reportedly caused several injuries to stunt performers during production

- Larry Semon was known for his whiteface makeup and wild, frantic comedy style that contrasted with the more subtle approaches of Chaplin or Keaton

- The film was part of a series of workplace comedies Semon produced, each featuring him in different industrial settings

- Semon's character's signature costume included a comically oversized hat and baggy clothes that enhanced his physical comedy

- The film's destruction sequence at the climax was considered particularly spectacular for its time, utilizing practical effects and real machinery

- This was one of several collaborations between Semon and Hardy, who appeared together in numerous comedies during this period

- The romantic subplot was typical of Semon's films, often serving as the motivation for the chaotic physical comedy sequences

- The film's title cards were written by Semon himself, who often contributed to the screenplays of his comedies

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like Variety and The Moving Picture World generally praised 'The Sawmill' for its energetic comedy and spectacular gags. Critics noted Semon's frantic performance style and the effective use of the industrial setting for comedic purposes. The film was considered typical of Semon's popular but formulaic approach to comedy. Modern film historians view the work as an interesting artifact of early 1920s comedy, noting its place in Semon's filmography and its early pairing of Hardy with a major comedy star. While not regarded as a masterpiece of silent comedy, it's acknowledged for its entertainment value and its representation of the diverse comedy styles available to audiences during the silent era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences, particularly fans of Larry Semon's wild comedy style. Moviegoers of the 1920s appreciated the film's fast-paced action, spectacular stunts, and straightforward romantic plotline. The workplace setting resonated with many viewers who could relate to the industrial environment, even if exaggerated for comedic effect. The film's success contributed to Semon's status as one of the more popular comedy stars of the early 1920s, though his popularity would wane later in the decade. The combination of physical comedy, romantic elements, and the familiar dynamic of the underdog triumphing over the bully proved to be a winning formula with audiences of the time.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charlie Chaplin's early comedies

- Buster Keaton's physical comedy style

- Harold Lloyd's everyman character

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedy approach

- Fatty Arbuckle's comedy shorts

This Film Influenced

- Later workplace comedies

- Physical comedy sequences in sound films

- Industrial setting comedies

- Three Stooges shorts

- Abbott and Costello routines

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'The Sawmill' is uncertain, as many silent films from this period have been lost. Some sources suggest that copies may exist in film archives or private collections, but a fully restored version is not widely available. The film, like many of Semon's works, has not received the preservation attention given to more famous silent comedies by Chaplin, Keaton, or Lloyd. Efforts by organizations like the Library of Congress and film preservation societies may have saved some copies, but access remains limited for researchers and the general public.