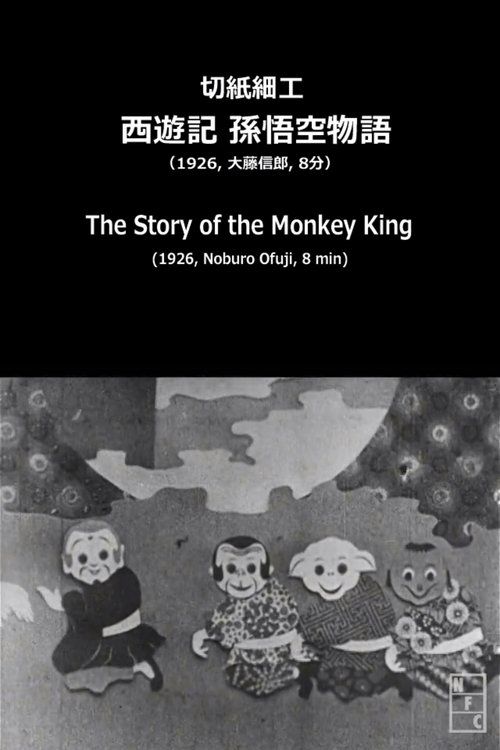

The Story of the Monkey King

Plot

This 1926 cut-out animation film adapts the classic Chinese novel 'Journey to the West,' focusing on the adventures of the Monkey King, Sun Wukong. The story follows the rebellious monkey deity who gains incredible powers through Taoist practices and causes chaos in heaven. After being imprisoned under a mountain for 500 years by the Buddha, he is freed by the monk Tripitaka to accompany him on a perilous journey to India to retrieve sacred Buddhist scriptures. Along the way, they encounter various demons and supernatural beings, with the Monkey King using his magical abilities and extendable staff to protect his master. The film captures the episodic nature of the original text, showcasing the Monkey King's transformation from a troublemaker to a devoted protector while maintaining his mischievous spirit.

Director

About the Production

Noburô Ôfuji created this film using his signature cut-out animation technique, which involved cutting out paper figures and moving them frame by frame. The animation was created using chiyogami, traditional Japanese decorative paper, giving the film a distinct aesthetic quality. As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance and a benshi (narrator) in Japanese theaters. The production was extremely labor-intensive, requiring thousands of individual paper cutouts and meticulous hand-positioning for each frame of animation.

Historical Background

The film was created in 1926, during the Taishō period in Japan, a time of significant cultural modernization and Western influence. Japanese cinema was transitioning from its early experimental phase to more sophisticated narrative forms, and animation was emerging as a new artistic medium. The 1920s saw the first wave of Japanese animated works, with pioneers like Ôfuji developing techniques that would lay the foundation for the future anime industry. This period also witnessed growing cultural exchange between Japan and China, making the adaptation of 'Journey to the West' particularly significant. The film predates the widespread adoption of sound in cinema, representing the pinnacle of silent-era animation in Japan. The devastation of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake had impacted Tokyo's film industry just a few years earlier, making works like this testaments to the resilience and creativity of Japanese filmmakers in the face of adversity.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a crucial milestone in the history of Japanese animation, demonstrating how early Japanese animators were adapting both foreign literary sources and emerging animation techniques to create distinctly Japanese works. The choice to adapt 'Journey to the West' reflects the enduring cultural connections between Japan and China, while the use of traditional chiyogami paper in the animation process shows how Ôfuji blended modern cinematic technology with traditional Japanese art forms. The film helped establish the Monkey King as a recurring character in Japanese popular culture, appearing in countless subsequent anime and manga adaptations. Ôfuji's cut-out animation technique would influence generations of Japanese animators, and the film stands as an important example of how Japanese animation developed its unique aesthetic identity separate from Western animation traditions. The surviving fragments of this film provide invaluable insight into the early development of anime and the creative methods of its pioneering animators.

Making Of

Noburô Ôfuji created this film during the early days of Japanese animation, working with limited resources but boundless creativity. The cut-out animation process was painstakingly manual - Ôfuji would cut each character and prop from paper, then photograph them frame by frame while making subtle adjustments to create the illusion of movement. The use of chiyogami paper was both practical and artistic, providing beautiful patterns that added visual richness to the simple animation style. As was common for silent films in Japan, theatrical screenings would feature a benshi (live narrator) who would provide voices, narration, and sound effects, dramatically enhancing the viewing experience. The film was produced during a period when Japanese animation was heavily influenced by Western techniques but was beginning to develop its own distinct aesthetic identity through the incorporation of traditional Japanese artistic elements.

Visual Style

The cinematography of this cut-out animation film was characterized by its use of flat paper figures photographed against static or minimally animated backgrounds. Ôfuji employed a top-down camera setup, positioning his paper cutouts on a flat surface and photographing them from above to create the animation sequence. The use of chiyogami paper with its intricate patterns added visual texture and depth to the otherwise two-dimensional animation style. The camera work was necessarily static due to the technical limitations of the time, but Ôfuji compensated through creative use of paper layering and positioning to suggest movement and depth. The black and white photography emphasized the silhouettes and shapes of the cut-out figures, creating a distinctive visual style that was both simple and expressive. The animation technique required precise control of lighting to ensure the paper figures were clearly visible while maintaining the desired artistic effect.

Innovations

Noburô Ôfuji's work on this film represented significant technical innovation in early Japanese animation. His refinement of cut-out animation techniques, using chiyogami paper for both aesthetic and practical purposes, demonstrated how traditional Japanese art forms could be adapted to the new medium of animation. The film showcased sophisticated understanding of movement and timing despite the technical limitations of cut-out animation. Ôfuji's ability to convey complex action sequences and emotional expressions through the manipulation of simple paper figures was a remarkable achievement for the time. The film's survival, even in fragmentary form, testifies to the durability of the materials and techniques used. Ôfuji's work on this film helped establish cut-out animation as a viable and distinctive animation technique in Japan, separate from the cel animation methods being developed in the West. The film represents an early example of how Japanese animators would consistently find innovative solutions to technical and budgetary constraints.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Story of the Monkey King' would have featured live musical accompaniment during theatrical screenings. The specific musical scores used are not documented, but it's likely that theaters employed traditional Japanese instruments alongside Western ones to create an appropriate atmosphere for the fantastical story. The benshi (live narrator) would have provided not only narration but also vocal characterizations and sound effects, essentially serving as the film's audio component. The musical accompaniment would have been improvised or drawn from existing musical pieces, adapted to fit the on-screen action and emotional tone of each scene. The combination of live music and benshi performance was standard practice for Japanese cinema of this period and was crucial to the audience's understanding and enjoyment of the film. The lack of synchronized sound meant that visual storytelling had to be exceptionally clear and expressive.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and the benshi's narration, making specific quotes difficult to document from surviving fragments

Memorable Scenes

- The Monkey King's rebellion in heaven, where he battles celestial armies using his extendable staff, showcasing Ôfuji's creative animation of action sequences through paper cutouts

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest surviving examples of Japanese animation, making it historically significant in the development of anime

- Director Noburô Ôfuji was a pioneer of cut-out animation in Japan and developed many techniques that would influence later animators

- The film was created using chiyogami, traditional Japanese patterned paper, giving it a unique visual style that blended traditional Japanese art with modern animation

- Despite its Japanese origin, the film adapts a Chinese literary classic, showing early cultural exchange between the two countries through cinema

- The original Japanese title was 'Songoku' (孫悟空), the Japanese reading of Sun Wukong's name

- Only fragments of this film are believed to survive today, as many early Japanese films were lost due to natural disasters and wartime destruction

- Ôfuji's animation technique involved photographing paper cutouts against backgrounds, a method he would continue to perfect throughout his career

- The film was part of a wave of Japanese animation in the 1920s that drew inspiration from both Western animation techniques and traditional Japanese art forms

- As a silent film, it relied heavily on visual storytelling, making the expressive potential of the cut-out animation crucial to narrative comprehension

- The Monkey King character would become one of the most frequently adapted figures in Japanese animation history

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the film is difficult to document due to the passage of time and loss of archival materials from the 1920s Japanese press. However, it was recognized as an innovative work within the small but growing community of Japanese animation enthusiasts. Modern film historians and animation scholars regard the film as a significant achievement in early Japanese animation, praising Ôfuji's technical skill and artistic vision. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of anime history as an important example of how Japanese animators developed their own distinct visual language. Animation historians particularly note the sophisticated use of cut-out techniques and the successful adaptation of complex literary material into the limited format of early animation. The film is considered a crucial piece of evidence in understanding the origins and development of anime as a unique cultural and artistic form.

What Audiences Thought

As with many films from this era, detailed records of audience reception are scarce. However, the Monkey King story was already familiar to Japanese audiences through various adaptations in traditional theater and literature, which likely helped the film find an appreciative viewership. The novelty of animation itself would have been a significant draw for audiences in 1926, as animated films were still a rarity in Japanese cinemas. The combination of a beloved story with the new medium of animation probably made the film popular among both children and adults. The presence of a benshi (narrator) during screenings would have enhanced the experience for Japanese audiences, who were accustomed to this form of cinematic storytelling. The film's success likely encouraged Ôfuji and other animators to continue exploring the possibilities of animation in Japan.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Journey to the West (16th century Chinese novel by Wu Cheng'en)

- Traditional Japanese paper art (origami and chiyogami)

- Early Western animation techniques

- Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints

- Traditional Japanese theater (kabuki and noh)

This Film Influenced

- Princess Mononoke (1997) - in its blending of traditional Japanese aesthetics with animation

- Paprika (2006) - in its innovative animation techniques

- The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013) - in its use of traditional artistic styles in animation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost, with only fragments surviving today. This is unfortunately common for early Japanese films due to the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, wartime destruction, and the fragile nature of early film stock. The surviving fragments are preserved in Japanese film archives and are occasionally shown in retrospectives of early animation. The incomplete nature of the surviving material makes it difficult to experience the film as originally intended, but the existing footage provides invaluable insight into early Japanese animation techniques and aesthetics.