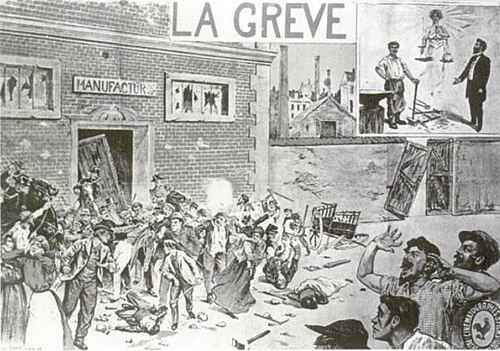

The Strike

Plot

In this early social drama, factory workers organize a strike to protest their harsh working conditions and low wages. The situation escalates violently when factory management calls in authorities to suppress the uprising, resulting in the deaths of several workers during the confrontation. One of the deceased workers' wives, consumed by grief and rage, seeks revenge by murdering the factory owner responsible for the deadly crackdown. During her subsequent trial, the factory owner's son, who understood his father's tyrannical treatment of workers, dramatically intervenes and pleads for mercy, acknowledging his father's culpability in the tragedy. Touched by this unexpected act of compassion and justice, the court ultimately acquits the grieving widow.

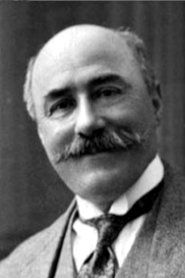

Director

About the Production

This film was produced during the peak of Pathé's dominance in early cinema, utilizing their state-of-the-art studio facilities in Vincennes, near Paris. The production would have been shot on 35mm film with hand-cranked cameras, requiring careful choreography for the crowd scenes depicting the strike. The film's social realist themes were relatively daring for the period, reflecting growing labor tensions in industrial France. Like many films of this era, it was likely shot in sequence with minimal editing, and intertitles would have been added to explain the narrative progression.

Historical Background

The Strike emerged during a tumultuous period in French labor history, just a few years after the landmark 1901 Law of Associations which legalized trade unions. France was experiencing significant industrialization and urbanization, leading to growing tensions between workers and factory owners. The early 1900s saw numerous strikes across France, particularly in mining and textile industries. This film was produced just two years after the 1902 Courrières mining disaster, which killed over 1,000 workers and highlighted dangerous working conditions. The film's release coincided with the rise of socialist political movements in France and growing public awareness of workers' rights issues. Cinema itself was still in its infancy - the Lumière brothers had only held their first public screening less than a decade earlier in 1895. Pathé Frères, under the leadership of Charles Pathé, was rapidly expanding from a phonograph company to become the world's dominant film producer and distributor.

Why This Film Matters

The Strike represents a crucial early example of cinema engaging with contemporary social and political issues, establishing film as a medium for social commentary rather than mere entertainment. Its sympathetic portrayal of labor struggles helped legitimize workers' concerns in popular culture during a period of intense class conflict. The film's narrative structure, combining social realism with dramatic personal tragedy, influenced subsequent socially conscious filmmaking. It demonstrated that even the primitive technology of early cinema could effectively address complex moral and ethical questions. The film's themes of justice, compassion, and social responsibility resonated with working-class audiences who were increasingly becoming cinema's primary demographic. This early engagement with class conflict in cinema prefigured the more politically explicit films of the 1920s and 1930s, including Soviet montage films that would directly address revolutionary themes. The film also represents an early example of cinema's role in documenting and interpreting contemporary social movements.

Making Of

The production of 'The Strike' took place during a revolutionary period in cinema's development. Ferdinand Zecca, as Pathé's creative director, was pioneering narrative filmmaking techniques that would influence generations of filmmakers. The cast would have consisted of stage actors from Parisian theaters, as dedicated film actors did not yet exist. The striking workers scenes required coordinating large groups of extras, a significant challenge for early film production. The film's sets were likely constructed in Pathé's glass studio buildings, which allowed for natural lighting while providing controlled conditions. The murder scene would have been particularly challenging to stage believably within the technical constraints of 1904 filmmaking. The courtroom finale required careful staging to convey the emotional weight of the son's testimony without dialogue. Like many Pathé productions of this era, the film was probably color-tinted by hand for certain scenes to enhance emotional impact, with red tones for violent moments and blue for somber scenes.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Strike reflects the technical limitations and aesthetic conventions of 1904. The film was likely shot using Pathé's proprietary cameras, which were hand-cranked and required careful operation to maintain consistent exposure. Static camera positions predominated, with the camera remaining fixed for each scene, a common practice in early cinema. The composition would have been theatrical in nature, with actors positioned to create clear visual narratives within the frame. Lighting would have relied primarily on natural light from the glass studio facilities, supplemented by arc lights when necessary. The film probably employed the tableau style of staging, with entire scenes playing out in long takes without editing. Visual storytelling was enhanced through the careful arrangement of actors and props to convey narrative information. The film may have utilized early special effects techniques for the murder scene, though these would have been rudimentary by modern standards. The visual aesthetic emphasized clarity and legibility over artistic experimentation, reflecting the primary goal of narrative comprehension.

Innovations

The Strike represents several technical achievements for its period, particularly in its ambitious narrative scope and social themes. The film's multi-scene structure, covering different locations and time periods, demonstrated the growing sophistication of cinematic storytelling in 1904. The coordination of crowd scenes depicting the strike required careful planning and execution, pushing the boundaries of what was technically possible in early film production. The film's use of intertitles to convey narrative information was relatively advanced for the period, helping audiences follow the complex plot developments. The production likely utilized Pathé's improved film stock and processing techniques, which were among the most advanced in the world at the time. The film's preservation of multiple narrative threads across its brief running time showed remarkable efficiency in storytelling. The technical execution of the murder scene, requiring careful timing and staging, demonstrated growing mastery of cinematic techniques. The film's distribution through Pathé's global network represented an achievement in international film distribution that few companies could match in 1904.

Music

As a silent film, The Strike would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition. Pathé often provided suggested musical scores for their films, typically consisting of classical pieces or popular melodies appropriate to each scene's emotional tone. The strike scenes might have been accompanied by dramatic, militaristic music, while the murder sequence would have used tense, dissonant compositions. The courtroom finale likely required more somber, reflective music to underscore the emotional weight of the son's plea for mercy. Large urban theaters might have employed small orchestras, while smaller venues would have used a single pianist or organist. The musical accompaniment played a crucial role in conveying emotion and narrative progression in the absence of dialogue. Some theaters may have used sound effects, particularly for the violent confrontation scenes. The musical experience would have varied significantly between exhibition venues, as standardization of film accompaniment was still decades away.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue exists from this silent film - any quotes would be from intertitles, which are not preserved in available records

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic courtroom scene where the factory owner's son dramatically pleads for mercy on behalf of his father's killer, creating a powerful moment of moral complexity and emotional catharsis that would have resonated strongly with early 20th century audiences

Did You Know?

- This is considered one of the earliest narrative films to explicitly address labor disputes and class conflict

- Director Ferdinand Zecca was Pathé's head of production and one of cinema's first true auteurs

- The film was released during a period of significant labor unrest in France, including numerous strikes and worker demonstrations

- Pathé Frères was the largest film company in the world at the time of this film's release

- The film's sympathetic portrayal of striking workers was unusual for commercial cinema of the period

- This film predates the establishment of many labor laws and workers' rights that would later be enacted in France

- The murder-revenge plot structure was innovative for its time, combining social commentary with dramatic entertainment

- Silent films of this era were often accompanied by live musical performance, with specific scores sometimes provided by the studio

- The film was likely distributed internationally through Pathé's extensive global distribution network

- 1904 was the same year that Pathé established its permanent theater chain, helping ensure films like this reached wide audiences

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of The Strike is difficult to document due to the limited film journalism of 1904, but trade publications likely noted its ambitious narrative scope and social relevance. The film would have been recognized as pushing the boundaries of what cinema could address thematically. Modern film historians and scholars view The Strike as an important early example of social realist cinema, though many note that its melodramatic elements reflect the theatrical conventions of the period. Critics today appreciate the film's historical significance as one of the first narrative films to explicitly address labor issues, even if some find its resolution overly sentimental. The film is often cited in academic studies of early cinema's engagement with social issues and its role in shaping public consciousness about class conflict. Its preservation and availability in film archives have allowed contemporary scholars to analyze its techniques and themes within the broader context of early 20th century French culture and cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Early 1900s audiences, particularly working-class viewers, likely responded strongly to The Strike's sympathetic treatment of labor issues. The film's dramatic narrative and clear moral framework would have been accessible to audiences still learning to understand cinematic storytelling. The combination of social relevance with personal tragedy probably resonated with viewers experiencing similar economic hardships. The film's relatively optimistic resolution, with mercy triumphing over vengeance, may have provided emotional satisfaction while still acknowledging the injustices of the industrial system. Contemporary accounts suggest that Pathé's dramatic films of this period were popular with urban audiences seeking both entertainment and emotional engagement. The film's themes would have been particularly relevant in industrial centers like Paris, Lyon, and Lille where labor tensions were high. Audience reactions to the film likely contributed to Pathé's continued production of socially conscious narratives throughout the 1900s.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage melodramas of the late 19th century

- Contemporary newspaper accounts of labor disputes

- Social realist literature of the period

- Earlier Pathé dramatic productions

- Theatrical traditions of French popular theater

This Film Influenced

- Later French social realist films of the 1920s and 1930s

- Soviet montage films dealing with labor themes

- Worker solidarity films of the 1930s

- French poetic realist films of the 1930s

- Later films addressing labor conflicts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of The Strike (1904) is uncertain - many Pathé films from this period have been lost due to the unstable nature of early nitrate film stock. Some fragments or copies may exist in film archives such as the Cinémathèque Française or the Library of Congress, but a complete, restored version may not be available. The film's historical significance has led to ongoing searches for surviving copies in international archives and private collections. Some portions may exist only in truncated form or as part of compilation reels. The film's survival would depend on whether Pathé made safety copies or if it was distributed to regions with better preservation conditions. Early cinema preservation efforts were virtually non-existent in 1904, making the survival of films from this period particularly rare.