The Suicide Sheik

Plot

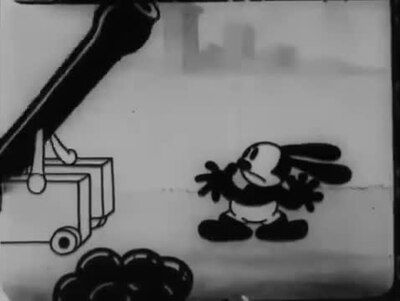

In this darkly comedic Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon, our hero is devastated when his beloved girlfriend leaves him for a wealthy rival. Heartbroken and despondent, Oswald attempts various methods of suicide, each failing in increasingly humorous ways. His attempts include trying to hang himself, jumping from a bridge, and even lying on railroad tracks, but fate intervenes at every turn. The cartoon culminates when his girlfriend returns, having realized the wealthy man was a fraud, and Oswald's depression immediately lifts. The film uses its morbid premise to showcase classic cartoon physics and visual gags, with Oswald's repeated failures at self-destruction serving as the main source of comedy.

Director

About the Production

This was one of the last Oswald cartoons produced before Walt Disney lost the character rights to Universal. The film was created during the critical transition period from silent to sound animation, though this particular short was released as a silent film. The dark subject matter was unusual even for the edgier comedy of the late 1920s, reflecting the more adult-oriented humor that characterized early animation before the Hays Code restrictions.

Historical Background

1929 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the full transition from silent films to 'talkies' following the success of 'The Jazz Singer' in 1927. The animation industry was in flux, with studios experimenting with sound synchronization and new character designs. The Great Depression was beginning to take hold, though its full impact wouldn't be felt until later in the year. This cartoon was produced during the height of the Oswald character's popularity, just before Disney's loss of the character rights would force a major shift in the animation landscape. The film's dark humor also reflected the more permissive attitudes of the late 1920s, before the implementation of the Hays Code would significantly restrict content in American films.

Why This Film Matters

'The Suicide Sheik' represents an important artifact from the early days of American animation, showcasing how edgy and experimental the medium was before industry self-regulation. The cartoon is part of the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit legacy, which directly led to the creation of Mickey Mouse and ultimately the Disney empire. Its treatment of dark themes in animation predates similar approaches by decades, showing that adult-oriented humor in cartoons is not a modern phenomenon. The film also serves as a valuable example of the transition period between silent and sound animation, capturing the technical and artistic evolution of the medium. As one of the surviving Oswald shorts, it helps preserve the legacy of one of animation's most influential early characters.

Making Of

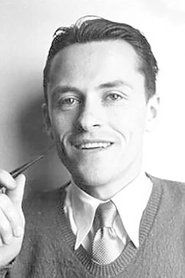

The production of 'The Suicide Sheik' occurred during a tumultuous period in animation history. Hugh Harman, working under producer Charles Mintz, was part of the Disney team that created Oswald but was caught in the middle of the contractual dispute that saw Disney lose the character. The cartoon was animated using traditional cel animation techniques of the era, with each frame hand-drawn and inked. The dark subject matter reflected the more experimental and adult nature of early animation, before the industry self-censored in response to public outcry. The animation team pushed boundaries with both the controversial theme and increasingly sophisticated gags, demonstrating the technical advances being made in cartoon comedy timing and visual storytelling.

Visual Style

The animation utilized the standard black and white silent film techniques of the era, with careful attention to contrast and visual clarity. The cartoon employed dynamic camera angles and movement unusual for the period, including tracking shots that followed Oswald's movements. The visual style featured the rubbery, exaggerated character designs typical of late 1920s animation, with Oswald's distinctive long ears and round body serving as key visual elements. The film made effective use of negative space and silhouettes, particularly in the suicide attempt sequences. The animation demonstrated increasing sophistication in timing and spacing, with gags carefully choreographed for maximum comedic impact.

Innovations

The cartoon demonstrated significant advances in animation fluidity and character expression compared to earlier works. The animators achieved more complex movements and emotional range in Oswald's character than in previous shorts. The film featured sophisticated timing in its gag sequences, with multiple layers of action occurring simultaneously. The use of perspective and depth in the bridge scene was particularly advanced for the period. The cartoon also showcased improved techniques in animating secondary action and follow-through, making the movement more believable despite the stylized nature of the characters. These technical achievements helped push the boundaries of what was possible in animation during the silent era.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Suicide Sheik' would have been accompanied by live musical accompaniment in theaters, typically performed by a theater organist or small orchestra. The score would have been compiled from standard photoplay music libraries, with selections chosen to match the on-screen action - dramatic music for the suicide attempts, romantic themes for the girlfriend scenes, and upbeat ragtime for the comedic moments. No original composed score was created specifically for this cartoon, which was standard practice for silent animated shorts. The lack of synchronized sound placed greater emphasis on visual storytelling and pantomime, skills at which the animators had become adept through years of silent film production.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) Oswald: 'My heart is broken! I shall end it all!'

(Intertitle) Oswald: 'Fate conspires against my demise!'

(Intertitle) Girlfriend: 'I was wrong! Wealth means nothing without true love!'

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where Oswald attempts to hang himself from a tree branch, only for the branch to snap and catapult him into the air, landing safely in a haystack. The scene perfectly exemplifies the cartoon's blend of dark theme and lighthearted execution, using impossible physics to turn a morbid situation into pure comedy.

Did You Know?

- This cartoon is considered one of the darkest in Oswald the Lucky Rabbit's filmography, dealing explicitly with suicide themes.

- The film was produced just months before Walt Disney lost the rights to Oswald, forcing him to create Mickey Mouse.

- Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising, who worked on this cartoon, would later co-found the animation department at MGM.

- The title is a play on the popular 1921 Rudolph Valentino film 'The Sheik'.

- Despite its dark theme, the cartoon was approved for general audiences, showing how much more permissive content standards were before the Hays Code.

- This was among the first cartoons to use the 'failed suicide attempts' trope that would later appear in many other animated series.

- The film showcases early examples of what would become cartoon physics laws, particularly the invulnerability of cartoon characters.

- Universal released this cartoon as part of their Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series, which was their answer to Disney's Mickey Mouse.

- The girlfriend character was one of the few recurring female characters in the Oswald series.

- This cartoon survives today in various film archives, though many Oswald shorts from this period are considered lost.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of the cartoon were generally positive, with trade publications like Variety and The Film Daily praising its inventive gags and animation quality, though some reviewers noted the unusually dark subject matter. Modern animation historians view the film as an important example of early animation's willingness to tackle taboo subjects for comedic effect. Critics today often cite it as evidence of how much more permissive early animation was compared to later eras. The cartoon is frequently discussed in academic works about animation history, particularly in studies examining the evolution of cartoon comedy and the impact of censorship on the medium.

What Audiences Thought

The cartoon was well-received by contemporary audiences who appreciated its bold humor and inventive gags. Movie theater audiences of the late 1920s were accustomed to more adult-oriented content in animated shorts, and the dark comedy didn't generate the controversy it might have in later decades. The Oswald character was extremely popular during this period, and his films consistently drew positive responses from theater-goers. Modern audiences encountering the cartoon often express surprise at its dark themes, reflecting how much animation content standards have changed over the decades. The film remains a curiosity piece for animation enthusiasts and historians interested in the medium's early days.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Sheik (1921 film)

- Felix the Cat cartoons

- Comedy films of Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton

- Vaudeville comedy traditions

- Silent film melodrama conventions

This Film Influenced

- Later cartoons featuring failed suicide gags

- Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies shorts of the 1930s

- Tom and Jerry cartoons

- Modern animated series that push content boundaries

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in 16mm and 35mm prints held by various film archives, including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. While not considered lost, some copies show varying degrees of deterioration typical of nitrate film from this period. The cartoon has been digitally restored by preservationists and is available through specialized animation archives and some public domain collections.