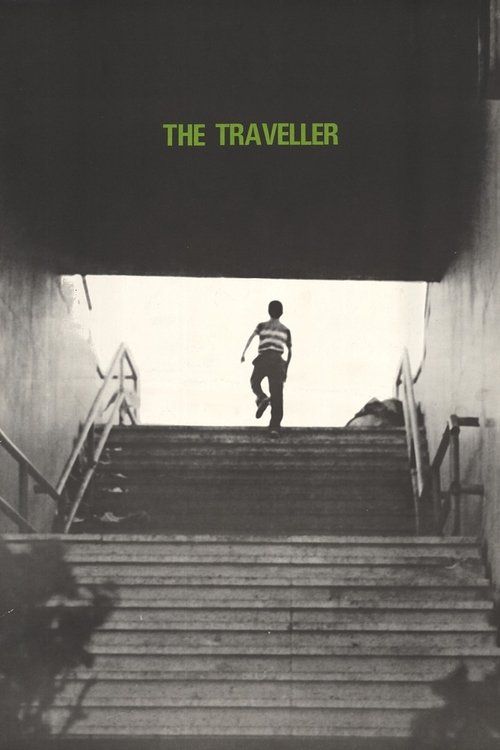

The Traveler

Plot

The Traveler follows Qassem, a resourceful and morally ambiguous 10-year-old boy living in a small Iranian town who becomes obsessed with seeing the Iran national football team play a crucial match in Tehran. When his attempts to get money from his family fail, Qassem embarks on a series of increasingly elaborate schemes to scam his classmates, neighbors, and local shopkeepers out of enough money for the bus ticket to the capital. His journey takes him through various encounters that reveal both his street-smart ingenuity and the moral compromises he's willing to make. The film culminates with Qassem finally reaching Tehran, only to face an unexpected and poignant reality check about his obsession and the nature of his journey. Kiarostami masterfully captures the boy's determination while subtly commenting on themes of childhood innocence, social inequality, and the gap between dreams and reality in pre-revolutionary Iran.

About the Production

The Traveler was produced by Kanoon, an organization dedicated to creating educational and cultural content for Iranian youth. Kiarostami, who was working extensively with Kanoon during this period, used non-professional actors from the local community to achieve authenticity. The film was shot on location in real locations rather than studio sets, a technique that would become a hallmark of Kiarostami's style. The production faced challenges typical of Iranian cinema in the 1970s, including limited resources and technical constraints. The football match scenes were particularly difficult to coordinate, requiring careful timing to capture the authentic atmosphere of a major sporting event.

Historical Background

The Traveler was created during a pivotal moment in Iranian history, just five years before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The mid-1970s represented a period of rapid modernization and Westernization under the Shah's regime, with cinema playing an increasingly important role in reflecting and shaping social change. The film emerged from Iran's burgeoning New Wave movement, which sought to move away from commercial cinema toward more artistically ambitious and socially relevant filmmaking. During this period, the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanoon) became an unlikely incubator for cinematic innovation, providing resources and creative freedom to filmmakers like Kiarostami. The film's focus on a working-class child's aspirations and struggles reflected growing social tensions and class disparities in Iranian society. The obsession with football and the national team also captured the rising importance of sports as a symbol of national pride and identity during this era of rapid modernization.

Why This Film Matters

The Traveler holds immense cultural significance as both a landmark in Iranian cinema and a foundational work in Abbas Kiarostami's oeuvre. The film established many of the themes and techniques that would define Kiarostami's later masterworks, including his focus on children as protagonists, his blend of documentary and fiction, and his exploration of the gap between desire and reality. The film's portrayal of working-class life in provincial Iran provided a rare window into a segment of society rarely depicted in Iranian cinema of the era. Its influence extended beyond Iran, introducing international audiences to the poetic realism of Iranian filmmaking and helping establish the country's reputation for producing sophisticated, humanistic cinema. The film's approach to child actors - treating them as collaborators rather than subjects - revolutionized how children were portrayed in cinema worldwide. The Traveler also represents an important document of pre-revolutionary Iran, capturing the social dynamics, urban-rural divide, and cultural aspirations of a society on the brink of profound transformation.

Making Of

The making of The Traveler represents a crucial period in Abbas Kiarostami's development as a filmmaker. Working with the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanoon), Kiarostami had developed a unique approach to working with non-professional child actors. For The Traveler, he spent months observing local children in the Koker region, eventually selecting Hassan Darabi for his natural charisma and street-smart demeanor. The director encouraged improvisation during filming, often letting the young actor discover moments organically rather than strictly following a script. The production team faced significant challenges filming in public spaces, particularly during the Tehran sequences where they had to work quickly and discreetly. Kiarostami's collaboration with cinematographer Firouz Malekzadeh established a visual language that would define much of his later work - a patient, observational style that finds poetry in everyday moments. The film's editing process was equally meticulous, with Kiarostami spending months shaping the raw footage to achieve the perfect balance between documentary realism and narrative storytelling.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Traveler, executed by Firouz Malekzadeh, exemplifies the observational, documentary-style approach that would become a hallmark of Kiarostami's work. The film employs natural lighting throughout, creating a sense of authenticity and immediacy that grounds the narrative in reality. Malekzadeh's camera work is characterized by its patient, contemplative framing, often holding shots longer than conventional narrative cinema to allow moments to unfold naturally. The cinematography captures the textures of provincial Iranian life with remarkable detail, from the dusty streets of the small town to the bustling energy of Tehran. The football sequences are particularly noteworthy, using handheld cameras and available light to create the chaotic excitement of a real sporting event. The visual language balances intimacy with distance, often observing the young protagonist from a respectful yet critical perspective. This approach allows viewers to empathize with Qassem while maintaining enough objectivity to recognize the moral implications of his actions.

Innovations

The Traveler represents several important technical achievements in the context of 1970s Iranian cinema. The film's innovative use of non-professional actors in lead roles demonstrated the potential for authentic performances outside the traditional studio system. Kiarostami's blending of documentary and narrative techniques created a hybrid form that would influence generations of filmmakers. The production's ability to film in real public spaces, including actual buses and football stadiums, with minimal disruption was remarkable for its time. The film's editing structure, which balances tight narrative pacing with observational moments, showed how commercial and artistic cinema could be successfully combined. The technical team's ability to capture high-quality sound in challenging real-world locations, particularly during the crowded football scenes, was particularly impressive given the limited equipment available. The film's successful integration of real events (the actual football match) within a fictional narrative predated later techniques like mockumentary and reality-based storytelling that would become more common in subsequent decades.

Music

The Traveler features a minimalist sound design that emphasizes natural ambient sounds over composed music. The film's audio landscape consists primarily of location sounds - the chatter of the town, the rumble of buses, the roar of the football crowd, and the everyday noises of Iranian urban and rural life. When music does appear, it's typically diegetic - songs playing on radios or music heard in public spaces - rather than a non-diegetic score. This approach reinforces the film's documentary-like authenticity and keeps the focus on the naturalistic performances and environmental details. The sound design during the football match scenes is particularly effective, using the actual crowd noise from the real Iran-Australia match to create an immersive experience. The sparse use of music heightens the impact of the few moments where it does appear, making them more emotionally resonant. This restrained approach to sound would become a signature element of Kiarostami's cinematic style throughout his career.

Famous Quotes

I don't care how I get there, I just have to see the match!

Everyone lies when they want something badly enough.

In Tehran, everything is possible. Here, nothing is.

A promise is just words until you keep it.

The game is more important than how you play it.

Memorable Scenes

- Qassem's elaborate scam where he pretends to collect money for school supplies while actually saving for his bus ticket

- The tense bus journey to Tehran where Qassem must hide his lack of a proper ticket

- The climactic scene at the football stadium where Qassem finally sees the match but faces an unexpected revelation

- The opening sequence showing Qassem's daily life in the small town and his obsession with football

- The confrontation scene where Qassem's teacher discovers his deception

Did You Know?

- Hassan Darabi, who plays Qassem, was not a professional actor but was discovered by Kiarostami in the local area where filming took place

- The film was one of Kiarostami's first feature-length works, coming after several short films made for Kanoon

- The actual football match depicted was a real World Cup qualifying match between Iran and Australia in 1973

- Kiarostami used natural lighting throughout the film to maintain documentary-like authenticity

- The film was banned for several years after the 1979 Iranian Revolution due to its depiction of pre-revolutionary society

- Many of the scam sequences were improvised by the young actor based on real childhood experiences

- The film's title in Persian is 'Mosafer' (مسافر), which literally means 'traveler' or 'passenger'

- Kiarostami considered this film a turning point in his approach to narrative filmmaking

- The bus journey scenes were filmed on actual public buses with hidden cameras to capture authentic reactions

- The film's screening at the 1974 Tehran International Film Festival marked Kiarostami's emergence as an important new voice in Iranian cinema

What Critics Said

Upon its release, The Traveler received acclaim from Iranian critics who recognized it as a significant achievement in the country's New Wave cinema. Critics praised Kiarostami's naturalistic direction, his ability to extract authentic performances from non-professional actors, and the film's subtle social commentary. International critics who discovered the film at festivals were particularly impressed by its documentary-like authenticity and universal themes. Over time, the film's reputation has grown, with many critics now considering it a crucial stepping stone in Kiarostami's artistic development and an important work in the history of world cinema. Contemporary critics often cite the film as an early example of Kiarostami's mastery of the poetic documentary style, noting how it prefigures themes he would explore more fully in later works like 'Where Is the Friend's Home?' and 'Close-Up'. The film is frequently analyzed in film studies for its innovative approach to narrative structure and its influence on subsequent generations of Iranian filmmakers.

What Audiences Thought

The Traveler initially found its primary audience among Iranian film enthusiasts and international art house cinema patrons. In Iran, audiences connected with the film's authentic portrayal of provincial life and its relatable young protagonist. Children and young adults particularly responded to Qassem's adventures and moral dilemmas. The film's banning after the 1979 Revolution limited its domestic viewership for years, but it developed a cult following among cinephiles who could access it through special screenings. International audiences who discovered the film through festival circuits and retrospectives were often struck by its universal themes and humanistic approach. In recent decades, as Kiarostami's international reputation has grown, The Traveler has been rediscovered by new audiences through DVD releases and streaming platforms, with many viewers noting its contemporary relevance despite being made nearly 50 years ago. The film's emotional resonance and moral complexity continue to engage viewers across cultural and generational divides.

Awards & Recognition

- Golden Plaque for Best Film, Tehran International Film Festival (1974)

- Best Director Award, Children's Film Festival, Tehran (1974)

- Best Actor Award (Hassan Darabi), Children's Film Festival, Tehran (1974)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian Neorealism (particularly De Sica's 'Bicycle Thieves')

- François Truffaut's 'The 400 Blows'

- Iranian documentary traditions

- Satyajit Ray's 'Apu Trilogy'

- Vittorio De Sica's 'Shoeshine'

- Social realist cinema of the 1960s

This Film Influenced

- Where Is the Friend's Home? (1987) - Kiarostami's own later work

- Close-Up (1990) - Kiarostami's documentary-narrative hybrid

- Children of Heaven (1997) - Majid Majidi

- The White Balloon (1995) - Jafar Panahi

- A Time for Drunken Horses (2000) - Bahman Ghobadi

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Traveler has been preserved through the efforts of international film archives and institutions dedicated to preserving Iranian cinema. The film was restored by the Criterion Collection as part of their Abbas Kiarostami box set, ensuring high-quality digital preservation. Original negatives are maintained at the Iranian National Film Archive, though political upheaval in Iran has sometimes complicated access and preservation efforts. The film has also been preserved by several international archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the British Film Institute. Digital restoration work completed in the 2010s has helped address deterioration issues with the original film elements. The restoration process involved extensive color correction and digital cleanup while maintaining the film's original aesthetic intentions.