The Twelve Labors of Hercules

Plot

This pioneering animated short film from 1910 presents the legendary Twelve Labors of Hercules through innovative cut-out animation techniques. The film chronologically depicts each of Hercules' famous tasks, from slaying the Nemean Lion to capturing Cerberus from the underworld. Using paper cut-outs moved frame by frame, Émile Cohl brings these mythological adventures to life with remarkable creativity for the era. The narrative follows the demigod's journey through his penance, showcasing his incredible strength and divine heritage as he completes each seemingly impossible task assigned by King Eurystheus. The film condenses these epic labors into a brief but comprehensive visual spectacle that captures the essence of ancient Greek mythology through early cinematic innovation.

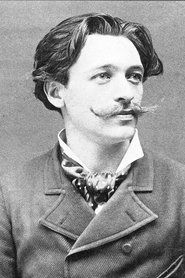

Director

About the Production

Created using Émile Cohl's pioneering cut-out animation technique, which involved cutting paper figures and moving them frame by frame. The production required meticulous hand-crafting of each character and background element, with Hercules and mythological creatures being carefully designed to allow for movement. The animation process was extremely labor-intensive, requiring each frame to be photographed individually. Cohl experimented with different paper types and joint mechanisms to achieve more fluid motion than in his earlier works.

Historical Background

This film was created during what historians now call the 'pioneering era' of animation (1900-1920), when filmmakers were still discovering the possibilities of the medium. In 1910, the film industry was rapidly expanding globally, with France leading in technical innovation and artistic ambition. The same year saw the rise of feature films and the establishment of Hollywood as a production center. Animation was still considered a novelty, with most animated shorts being shown as part of variety programs alongside live-action comedies and magic acts. The choice of classical mythology as subject matter reflected the era's fascination with ancient culture and the educational aspirations of early cinema. This period also saw the beginning of the transition from simple trick films to more sophisticated animated storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest narrative animated films, 'The Twelve Labors of Hercules' represents a crucial milestone in the development of animation as an art form capable of telling complex stories. The film demonstrated that animation could handle episodic narratives, paving the way for future animated series and features. Its use of classical mythology helped establish animation as a medium capable of adapting literary and cultural material, not just creating simple gags. The film's technical innovations in cut-out animation influenced other early animators and contributed to the development of more sophisticated animation techniques. It also represents an important example of French contributions to early animation history, which is often dominated by American figures in popular narratives.

Making Of

Émile Cohl created this film while working as the head of Gaumont's animation department, one of the first such departments in cinema history. The production took place in a small Paris studio where Cohl and his assistants would spend weeks crafting the paper figures and backgrounds. Each character joint was carefully engineered with tiny pins or paper tabs to allow for movement while maintaining structural integrity. The animation was shot on a custom-built rostrum with the camera positioned directly above the work surface. Cohl would often work late into the night, personally manipulating the figures while his assistant cranked the camera handle. The mythological subject matter was chosen to appeal to educated audiences of the time who were familiar with classical stories, while also showcasing the technical possibilities of the new medium of animation.

Visual Style

The film was shot using a stationary camera positioned directly above the animation surface, a technique that became standard for 2D animation. The lighting was carefully controlled to eliminate shadows from the animators' hands and create even illumination across the paper figures. Each frame was exposed manually, requiring precise timing and consistency. The cinematography emphasized clarity over dramatic angles, as the focus was on showcasing the animated movement. The original film stock was likely black and white 35mm, with some versions possibly hand-colored using stencils. The camera work was functional rather than artistic, serving primarily to capture the animation clearly.

Innovations

This film represents a significant advancement in cut-out animation technique, with more sophisticated joint mechanisms allowing for greater expressiveness in character movement. The successful condensation of twelve distinct episodes into a cohesive narrative demonstrated new possibilities for animated storytelling. The film's production workflow established patterns for animation production that would influence future studios. Cohl's experimentation with different paper weights and textures to achieve various visual effects was innovative for the time. The film also demonstrated early approaches to character consistency across multiple scenes, a crucial technical challenge in animation that would continue to evolve throughout the century.

Music

The original film was silent, as all films were in 1910. During theatrical exhibition, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing classical or popular pieces appropriate to the mythological subject matter. The music would have been chosen to match the mood of each labor - dramatic music for battles, lighter themes for moments of triumph. Some theaters may have used specific musical cues synchronized with the action, though this was not standardized. Modern screenings often feature newly composed scores or carefully selected classical music that reflects the film's early 20th century origins.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue - silent film with intertitles

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence depicting Hercules battling the Nemean Lion, where the cut-out animation creates a surprisingly dynamic struggle between hero and beast

- The climactic scene of Hercules capturing Cerberus, which used layered paper cut-outs to create depth and drama

- The montage sequence rapidly showing all twelve labors, demonstrating the ambitious scope of the project

Did You Know?

- Émile Cohl, often called 'the father of the animated cartoon,' was already 53 years old when he made this film

- The film was created using cut-out animation, one of the earliest animation techniques, predating cel animation

- This was one of the first animated films to tackle a complete narrative arc with multiple distinct episodes

- The Twelve Labors of Hercules was part of Cohl's series of mythological and historical animated shorts for Gaumont

- Each labor had to be condensed into mere seconds of screen time due to the brevity of early films

- The original film was likely hand-colored frame by frame, a common practice for important French films of this era

- Cohl's animation studio was one of the first dedicated animation production facilities in the world

- The film was released during the peak of the French film industry's global dominance before World War I

- Cut-out animation was chosen over other techniques because it allowed for more detailed character designs than simple line drawings

- The film's survival is remarkable, as approximately 90% of films from this era are considered lost

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in French film journals praised the film's technical achievement and imaginative approach to animation. Critics noted the fluidity of motion compared to earlier animated works and appreciated the ambitious scope of adapting all twelve labors. Modern film historians recognize it as an important technical achievement that demonstrated the narrative potential of animation. The film is frequently cited in academic works on early animation history as an example of Émile Cohl's mature style and his contributions to establishing animation as a serious art form. Animation scholars particularly value the film for its preservation of early cut-out animation techniques that would soon be replaced by more efficient methods.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1910 reportedly marveled at the magical quality of the moving paper figures, with the mythological subject matter providing familiar entertainment for educated viewers. The film was popular enough to be exported to other countries, where it was often shown with translated intertitles. Children particularly responded to the fantastic elements and heroic story, helping establish animation as family entertainment. The brevity of each labor segment kept audiences engaged throughout the short runtime. Modern audiences viewing restored versions are often struck by the creativity and charm of the primitive animation technique, finding historical value in witnessing the early development of animated storytelling.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Greek mythology

- J.J. Grandville's illustrated works

- Gaston Leroux's theatrical adaptations

- Georges Méliès's trick films

- Winsor McCay's early animation experiments

This Film Influenced

- Later Hercules adaptations in animation

- Émile Cohl's subsequent mythological shorts

- Early Disney mythological cartoons

- Paul Terry's mythological animations

- Fleischer Studios' mythological shorts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - some reels exist in film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. The film is considered incomplete, with some segments possibly lost. Restoration efforts have stabilized existing footage and digitally enhanced visibility. The surviving portions provide valuable documentation of early animation techniques. Some versions may be incomplete or show significant deterioration due to the age and fragility of early film stock.