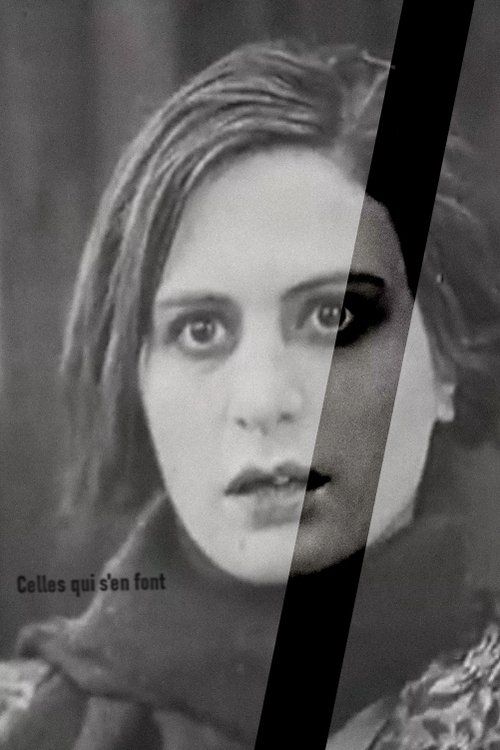

Those Who Worry

Plot

The film follows the tragic story of a destitute alcoholic woman who, in her drunken despair, appears to romanticize and yearn for the life of a streetwalker. Through a series of impressionistic vignettes, the protagonist drifts through Parisian streets, her reality blurring with fantasies of an alternative existence. The narrative explores her psychological deterioration as she confronts her social marginalization and internal conflicts. Dulac employs avant-garde techniques to visualize the woman's fragmented consciousness and her complex relationship with societal expectations. The film culminates in a powerful meditation on female agency, poverty, and the illusion of choice in constrained circumstances.

Director

About the Production

This was one of Dulac's later silent works, created during the transitional period when sound cinema was emerging. The film was shot on location in Paris, utilizing natural urban environments to enhance the realism of the protagonist's marginal existence. Dulac employed innovative camera techniques including subjective POV shots and superimposition to represent the character's psychological state. The production faced challenges due to the rapidly changing film industry landscape of 1928, as studios were shifting focus to sound production.

Historical Background

1928 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the final peak of silent film artistry before the sound revolution transformed the industry. In France, this period saw the culmination of the Impressionist movement and the emergence of Surrealist influences in cinema. Germaine Dulac, as a prominent female director in a male-dominated field, was pushing boundaries both thematically and technically. The film's exploration of female marginalization reflected broader social tensions in post-WWI France, where women's roles and societal positions were in flux. The late 1920s also saw increased interest in psychological realism and social commentary in European cinema, with filmmakers addressing contemporary issues of poverty, mental health, and social inequality.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of female authorship in early cinema, showcasing Germaine Dulac's unique perspective on women's experiences and social issues. As part of the French avant-garde movement, it contributed to the development of cinematic language for expressing psychological states and social critique. The film's focus on a marginalized female protagonist was groundbreaking for its time, offering a rare cinematic exploration of working-class women's lives from a female perspective. Its experimental techniques influenced subsequent developments in art cinema and psychological drama. The film stands as a testament to Dulac's role as a pioneer feminist filmmaker who used cinema as a medium for social commentary and artistic innovation.

Making Of

Germaine Dulac approached this film with her characteristic blend of social consciousness and formal experimentation. Working with cinematographer Maurice Forster, she developed techniques to visualize the protagonist's internal psychological state through visual metaphors and innovative editing. The casting of Lilian Constantini was significant, as she brought a naturalistic quality that aligned with Dulac's interest in authentic performances. The film was shot quickly during a period of intense creative output for Dulac, who was simultaneously working on other projects and advocating for avant-garde cinema. The production team faced the challenge of creating a serious psychological drama while the film industry was shifting toward commercial sound productions.

Visual Style

The cinematography employs innovative techniques characteristic of French Impressionist cinema, including soft focus, superimposition, and subjective camera angles to represent the protagonist's psychological state. The visual style uses contrast between the gritty reality of Parisian streets and dreamlike sequences that blur the boundaries between fantasy and reality. Camera movement and unconventional framing create a sense of disorientation that mirrors the character's mental state. The black and white photography emphasizes the stark contrasts between light and shadow, symbolizing the character's moral and social conflicts. The cinematographic approach reflects Dulac's interest in using visual language to convey emotional and psychological depth beyond conventional narrative techniques.

Innovations

The film demonstrates advanced use of cinematic techniques for its time, including innovative editing patterns that convey psychological states through rhythmic cuts and juxtapositions. Dulac employed superimposition and double exposure techniques to represent the character's internal conflicts and fantasies. The use of location shooting in Parisian streets added authenticity to the portrayal of urban marginalization. The film's pacing and rhythm reflect Dulac's understanding of cinema as a temporal art form capable of expressing complex psychological realities. These technical innovations contributed to the development of cinematic language for expressing subjective experience and social commentary.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score likely consisted of classical pieces or original compositions that emphasized the dramatic and psychological elements of the narrative. Modern screenings of restored versions typically feature newly composed scores that respect the film's avant-garde nature and emotional tone. The absence of synchronized dialogue allows the visual storytelling and musical accompaniment to create the film's emotional impact. The musical choices would have been crucial in establishing the mood and enhancing the film's exploration of psychological distress.

Did You Know?

- This film is one of Germaine Dulac's lesser-known works from her avant-garde period

- The film was created just before Dulac's career was significantly impacted by the transition to sound cinema

- Lilian Constantini, who plays the protagonist, was a frequent collaborator with Dulac in her later films

- The film's themes of female marginalization were highly progressive for its time period

- Dulac was part of the French Impressionist cinema movement and this film reflects those stylistic influences

- The original French title may have been 'Celles qui s'inquiètent' or similar

- The film was produced during the height of Dulac's feminist filmmaking period

- It represents Dulac's interest in psychological realism combined with formal experimentation

- The film's focus on a working-class woman was unusual for the art cinema of its era

- Dulac was one of the few prominent female directors working in France during the 1920s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the film is difficult to trace due to limited documentation from the period, but it was likely overshadowed by the industry's transition to sound. Modern film scholars and critics have rediscovered the work as an important example of Dulac's mature style and her commitment to feminist themes. Critics today praise the film's visual innovation and its sensitive portrayal of female psychological distress. The film is now recognized as part of Dulac's significant contribution to avant-garde cinema and her role as a pioneering female director. Recent retrospectives of Dulac's work have brought renewed attention to this film and its place in cinema history.

What Audiences Thought

Original audience reception is not well documented, but the film likely reached limited audiences due to its avant-garde nature and the timing of its release during the sound transition. Modern audiences who have discovered the film through film festivals and retrospectives have responded positively to its artistic merits and historical significance. The film's themes continue to resonate with contemporary viewers interested in feminist cinema and early film history. Its preservation and presentation in film archives have allowed new generations to appreciate Dulac's visionary work. The film serves as an important educational resource for those studying women's contributions to early cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French Impressionist cinema

- Surrealist movement

- German Expressionist cinema

- Psychological realism in literature

- Feminist theory of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- Later French poetic realist films

- Feminist avant-garde cinema of the 1970s

- Psychological drama films

- Social realist cinema