Germaine Dulac

Director

About Germaine Dulac

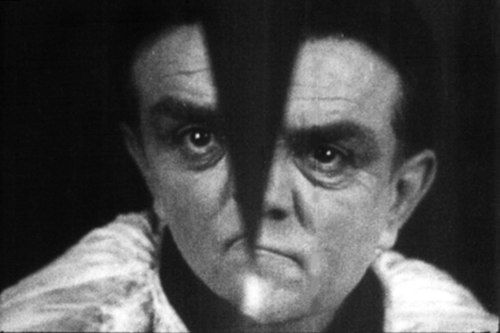

Germaine Dulac (born Charlotte Elisabeth Marie Germaine Dulac) was a pioneering French filmmaker, screenwriter, and film theorist who emerged as one of the most significant figures in French avant-garde cinema during the 1920s. She began her career as a journalist and theater critic before transitioning to film, initially working with her husband who financed her early productions. Dulac quickly established herself as a formidable director, creating works that explored feminist themes and experimented with cinematic techniques that pushed the boundaries of narrative filmmaking. Her 1923 film 'The Smiling Madame Beudet' is widely regarded as one of the first feminist films in cinema history, while 'The Seashell and the Clergyman' (1928) is often cited as the first surrealist film. Beyond her directing work, Dulac was an influential film theorist who advocated for cinema as a pure art form, writing extensively about the medium's potential for visual expression and emotional impact. She served as president of the French Federation of Ciné-Clubs and was instrumental in promoting artistic cinema throughout France. Despite facing gender discrimination in a male-dominated industry, Dulac directed approximately 30 films and left an indelible mark on cinematic history before her death in 1942.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Germaine Dulac's directing style was characterized by its innovative visual techniques, psychological depth, and avant-garde approach to narrative. She employed impressionistic cinematography, using soft focus, superimpositions, and rhythmic editing to convey characters' inner states and emotions. Dulac was a master of visual symbolism, often using objects and settings to represent psychological themes rather than relying solely on dialogue or traditional plot development. Her feminist perspective manifested through her focus on female subjectivity and critique of patriarchal social structures. She believed in 'pure cinema' - the idea that film should express ideas and emotions through visual means rather than literary conventions. Dulac's work frequently experimented with temporal manipulation, dream sequences, and abstract imagery, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in narrative cinema of her era.

Milestones

- Directed 'The Smiling Madame Beudet' (1923), considered one of the first feminist films

- Created 'The Seashell and the Clergyman' (1928), often cited as the first surrealist film

- Served as President of the French Federation of Ciné-Clubs

- Pioneered impressionist and avant-garde cinema techniques in France

- Authored influential theoretical writings on cinema as pure art

- Became one of the first successful female film directors in history

- Advocated for feminist themes and perspectives in early cinema

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Legion of Honor (1935)

Special Recognition

- President of the French Federation of Ciné-Clubs (1928-1930)

- Pioneer of feminist cinema recognized by film historians worldwide

- Retrospectives at major film festivals including Cannes and Venice

- Inducted into the International Women's Forum Hall of Fame

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Germaine Dulac's cultural impact extends far beyond her filmography, as she fundamentally challenged both the technical and thematic conventions of early cinema. As one of the first female directors to achieve international recognition, she paved the way for future generations of women in film, demonstrating that women could successfully direct technically and artistically ambitious films. Her feminist approach to storytelling, particularly in 'The Smiling Madame Beudet,' introduced female subjectivity into cinema at a time when most films presented women through male perspectives. Dulac's theoretical writings on 'pure cinema' influenced the development of film theory worldwide, contributing to the understanding of cinema as a distinct art form rather than merely recorded theater. Her work with the French Federation of Ciné-Clubs helped create a culture of film appreciation and criticism that elevated cinema from popular entertainment to artistic expression. The surrealist techniques she pioneered in 'The Seashell and the Clergyman' influenced countless filmmakers and contributed to the development of surrealist cinema as a significant movement.

Lasting Legacy

Germaine Dulac's legacy as a cinematic pioneer has grown significantly since her death, with modern film scholars recognizing her as one of the most important figures in early avant-garde cinema. Her films are now studied in universities worldwide as examples of early feminist filmmaking and surrealist cinema. The rediscovery of her work in the 1970s by feminist film scholars led to a reevaluation of her contributions to cinema history. Dulac's theoretical writings on pure cinema continue to influence contemporary filmmakers interested in visual storytelling beyond conventional narrative structures. The Germaine Dulac Award, established in her honor, recognizes outstanding contributions to feminist filmmaking. Her life and work have inspired numerous books, documentaries, and academic conferences dedicated to preserving and analyzing her contributions to cinema. As technology has made her films more accessible, new generations of filmmakers and film enthusiasts continue to discover and draw inspiration from her innovative techniques and progressive themes.

Who They Inspired

Germaine Dulac's influence on subsequent filmmakers is both direct and profound, particularly in the realms of feminist cinema and surrealist filmmaking. Her visual techniques and narrative innovations influenced French New Wave directors like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, who admired her rejection of conventional storytelling. Surrealist filmmakers including Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí drew inspiration from her dreamlike imagery and psychological explorations in 'The Seashell and the Clergyman.' Feminist directors from Agnès Varda to Chantal Akerman have acknowledged Dulac as a pioneering voice who established the possibility of women's perspectives in cinema. Her theoretical writings on pure cinema influenced experimental filmmakers like Maya Deren and Stan Brakhage, who shared her belief in cinema's potential for abstract expression. Contemporary directors including Sally Potter, Jane Campion, and Agnieszka Holland have cited Dulac as an influence in their pursuit of visually distinctive and thematically challenging cinema. Her work continues to be taught in film schools as an example of how cinema can transcend entertainment to become a medium for artistic expression and social commentary.

Off Screen

Germaine Dulac was born into an upper-middle-class family in Amiens, France, and received a privileged education that included music and art. In 1905, she married engineer and industrialist Marie-Louis Albert-Dulac, who supported her artistic ambitions and financed her early film productions. The couple separated in 1920 but remained on good terms, with Albert-Dulac continuing to support her work financially. Dulac was openly bisexual and had relationships with both men and women, which was unusual for her time. She was known for her intellectual circle of friends, including writers, artists, and fellow filmmakers. Despite her professional success, she faced significant gender discrimination throughout her career, often having to work harder than her male counterparts to gain recognition and funding for her projects. She spent her final years in Paris, continuing to write about film theory and advocate for artistic cinema until her death in 1942.

Education

Educated at convent schools in Paris, studied music and art, received formal education in literature and philosophy

Family

- Marie-Louis Albert-Dulac (1905-1920)

Did You Know?

- Her real first name was Charlotte, but she used Germaine professionally

- She was a talented pianist before becoming involved in cinema

- Her 1918 animated film 'The Sinking of the Lusitania' was one of the first animated documentaries

- Dulac was a member of the French Communist Party for several years

- She founded the first film club in France with Louis Delluc

- Her film 'The Seashell and the Clergyman' was initially banned by British censors

- Dulac directed approximately 30 films during her career, though many are now lost

- She was one of the first directors to use psychoanalytic theory in filmmaking

- Dulac's work was nearly forgotten until feminist film scholars rediscovered it in the 1970s

- She was friends with influential artists including Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp

- Dulac wrote a regular column on cinema for the French newspaper Le Petit Parisien

- She believed that cinema should be 'the visual expression of the soul' rather than photographed theater

In Their Own Words

Cinema must be freed from the tyranny of the photographed theater

The cinema is the art of the eye, not the art of the word

I want to make films that are poems, not novels

The camera is not a recording instrument, but a creative instrument

Pure cinema is the visual expression of ideas and emotions without the aid of literature

Women in cinema must not merely be objects of the gaze, but subjects of their own stories

The future of cinema lies in its ability to dream, not to document

Every frame should be a painting, every cut a revelation

Cinema's greatest power is its ability to make visible the invisible

I make films not to show life, but to interpret it

Films

5 films