The Seashell and the Clergyman

"A Dream of a Film - The First Surrealist Masterpiece"

Plot

The Seashell and the Clergyman follows a tormented clergyman who becomes obsessively fixated on a general's wife, experiencing a series of increasingly surreal and disturbing visions that blur the boundaries between reality and fantasy. As his repressed desires and religious guilt manifest in bizarre dream sequences, the clergyman navigates through symbolic landscapes filled with seashells, locked doors, and mysterious women representing his unfulfilled lust. The narrative deliberately abandons conventional storytelling, instead presenting a psychological journey through the clergyman's subconscious as he struggles against his own eroticism and spiritual corruption. The film culminates in a series of disjointed, symbolic episodes where the clergyman attempts to possess the general's wife, ultimately leading to his psychological disintegration in a world where his religious devotion and carnal desires become indistinguishable.

Director

About the Production

The film was based on a scenario by Antonin Artaud, though he famously disapproved of Dulac's interpretation, claiming she had 'trivialized' his work. The production faced significant challenges due to its controversial subject matter and experimental nature. Shot in 1928 during the height of the surrealist movement, the film utilized innovative techniques including superimposition, rapid montage, and distorted perspectives to create its dreamlike atmosphere. The production team worked with limited resources, relying heavily on creative set design and optical effects to achieve the surreal visual style.

Historical Background

The Seashell and the Clergyman was created during a period of tremendous artistic and social upheaval in Europe. The late 1920s saw the rise of surrealism as a major artistic movement, with figures like André Breton, Salvador Dalí, and Luis Buñuel challenging conventional notions of art and reality. In France, the film industry was transitioning from the impressionist style of the early 1920s to more experimental and avant-garde approaches. The period between the World Wars was marked by a rejection of traditional values and an exploration of the subconscious mind, influenced heavily by the theories of Sigmund Freud. The film emerged alongside other revolutionary artistic works that sought to break free from narrative constraints and explore the irrational aspects of human experience. Additionally, 1928 was a year of significant technological change in cinema, with the transition to sound beginning to threaten the art form of silent film, making Dulac's work particularly significant as a pinnacle of silent cinematic artistry.

Why This Film Matters

The Seashell and the Clergyman holds immense cultural significance as a groundbreaking work that helped establish the language of surrealist cinema. Its influence extends far beyond its initial reception, impacting countless filmmakers who sought to explore psychological and dream states through visual media. The film challenged the dominant narrative structures of classical cinema and opened doors for more experimental approaches to filmmaking. As one of the few major surrealist films directed by a woman, it represents an important contribution to feminist film history and the broader narrative of women's roles in early cinema. The film's exploration of religious repression and sexual desire was remarkably bold for its time, pushing boundaries of what could be depicted on screen. Its rediscovery and restoration in the 1960s coincided with a renewed interest in avant-garde cinema, influencing experimental filmmakers of the New Wave and beyond. Today, it is studied in film schools worldwide as a prime example of how cinema can transcend literal storytelling to explore the depths of human consciousness.

Making Of

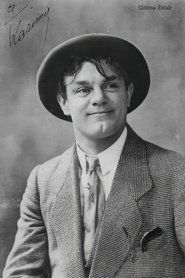

The production of 'The Seashell and the Clergyman' was marked by significant creative conflict between writer Antonin Artaud and director Germaine Dulac. Artaud had written the scenario as an exploration of his theories about the 'theater of cruelty' and wanted the film to be a shocking, visceral experience. However, Dulac, with her background in impressionist cinema and feminist perspectives, interpreted the material through a more psychological and symbolic lens. The cast, led by Alex Allin as the clergyman and Genica Athanasiou as the general's wife, worked with Dulac to create performances that emphasized the dreamlike, subconscious aspects of the narrative. The film was shot quickly and cheaply in Paris studios, with the production team relying heavily on painted backdrops, mirrors, and primitive special effects to achieve the surreal atmosphere. Despite the artistic tensions, the film was completed and premiered to scandalized reactions, with many critics and audience members confused by its non-linear narrative and shocking imagery.

Visual Style

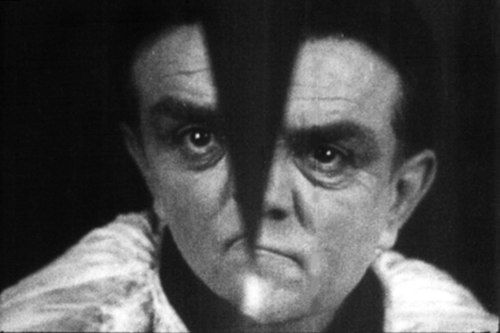

The cinematography of 'The Seashell and the Clergyman' was revolutionary for its time, employing numerous innovative techniques to create its dreamlike atmosphere. Cinematographer Maurice Forster and director Germaine Dulac utilized extensive superimposition, multiple exposures, and distorted lenses to achieve surreal visual effects that would become hallmarks of surrealist cinema. The film features dramatic lighting contrasts, with deep shadows and bright highlights creating a chiaroscuro effect that emphasizes the psychological tension between repression and desire. Camera movement is deliberately unconventional, with Dutch angles, rapid pans, and disorienting tracking shots that contribute to the sense of psychological unease. The use of mirrors and reflective surfaces throughout the film creates a fragmented visual space that mirrors the clergyman's fractured psyche. The visual composition frequently breaks the rules of classical cinematography, with off-center framing and unusual perspective choices that reinforce the film's rejection of conventional reality. The black and white photography is particularly striking in its use of texture and pattern, with the seashell motif recurring in various forms throughout the visual narrative.

Innovations

The film achieved numerous technical innovations that were groundbreaking for 1928. The extensive use of superimposition and multiple exposure techniques to create ghostly, dreamlike effects was particularly advanced for the period. The production team developed innovative methods for creating distorted perspectives using specially modified lenses and angled mirrors, effects that would later become staples of surrealist and psychological horror cinema. The film's editing style, with its rapid cuts and disorienting montage sequences, pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in narrative filmmaking. The creation of surreal set designs and props, including the iconic oversized seashells, demonstrated remarkable creativity within the technical limitations of the era. The film's successful integration of these various technical elements into a coherent artistic vision represented a significant achievement in cinematic artistry. The preservation and restoration of the film over the decades has also involved significant technical challenges, with modern digital restoration techniques helping to maintain the film's visual impact while ensuring its survival for future generations.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Seashell and the Clergyman' was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and venue. The score was typically provided by a house organist or small ensemble who would improvise or adapt classical pieces to match the film's mood and action. Some theaters used existing classical compositions, particularly works by Debussy, Ravel, or other impressionist composers whose music complemented the film's dreamlike quality. In the 1960s and 1970s, when the film was rediscovered and screened for new audiences, contemporary composers created new scores specifically for the film, often incorporating avant-garde and experimental elements that echoed the film's surreal imagery. Modern restorations and screenings typically feature specially commissioned scores that range from classical to experimental electronic music, reflecting the film's enduring influence and versatility. The absence of synchronized sound actually enhances the film's surreal quality, forcing viewers to engage more deeply with the visual imagery and creating a more dreamlike experience.

Famous Quotes

I am the seashell, and you are the clergyman who desires me - spoken by the General's wife in a dream sequence

The doors of perception open only to those who dare to close their eyes - intertitle

In dreams, God and the Devil dance together - intertitle

Your prayers are but poetry to my ears - the General's wife to the clergyman

The soul is a prisoner in the body's shell - intertitle

When the spirit breaks, the flesh rejoices - intertitle

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the clergyman sees a giant seashell in his study, which then transforms into the General's wife, establishing the film's surreal visual language and central motif.

- The scene where the clergyman attempts to climb an endless staircase that leads nowhere, symbolizing his futile struggle against his own desires.

- The famous mirror sequence where the clergyman sees multiple distorted reflections of himself, each representing different aspects of his repressed personality.

- The beach scene where the clergyman chases the General's wife across a shore filled with giant seashells that open and close like hungry mouths.

- The final sequence where the clergyman finds himself in a room with multiple doors, each leading to another surreal landscape, representing his complete loss of reality.

Did You Know?

- Considered by many film historians to be the first truly surrealist film ever made, predating Buñuel's 'Un Chien Andalou' by several months.

- The scenario was written by Antonin Artaud, who publicly denounced the film after its premiere, claiming director Germaine Dulac had 'betrayed' his vision.

- The film was initially banned in the UK by the British Board of Film Censors for being 'so obscure as to have no meaning' and potentially harmful to audiences.

- Germaine Dulac was one of the few prominent female directors of the silent era and a pioneer of feminist filmmaking.

- The famous seashell motif appears throughout the film as a Freudian symbol of female sexuality and the clergyman's repressed desires.

- The film's original French title 'La Coquille et le Clergyman' directly translates to 'The Shell and the Clergyman'.

- Despite Artaud's objections, the film was embraced by the surrealist group including André Breton, who praised its revolutionary approach to cinema.

- The film was lost for decades before being rediscovered and restored in the 1960s, leading to its reevaluation as a masterpiece of avant-garde cinema.

- Only one copy of the film was known to survive until additional prints were discovered in European archives in the 1980s.

- The clergyman's visions were achieved through innovative in-camera effects rather than post-production, as editing technology was limited in 1928.

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, critical reception was deeply divided and often hostile. Many mainstream critics dismissed the film as incomprehensible nonsense, with the British Board of Film Censors famously declaring it 'so obscure as to have no meaning.' However, avant-garde circles and surrealist publications embraced it enthusiastically, with André Breton and other surrealists defending its revolutionary approach to cinema. The conflict between Artaud and Dulac became a topic of critical discussion, with some siding with Artaud's vision of pure shock while others appreciated Dulac's more psychological interpretation. Over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, with modern critics recognizing the film as a masterpiece of surrealist cinema. Contemporary scholars praise its innovative visual techniques, psychological depth, and its role in establishing surrealist cinema as a legitimate artistic movement. The film is now widely regarded as one of the most important experimental films of the silent era, with its influence evident in the work of countless subsequent filmmakers from David Lynch to David Cronenberg.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was largely negative and confused, with many viewers finding the film's non-linear narrative and surreal imagery baffling and disturbing. Reports from the premiere describe audience members walking out in confusion or protest, unaccustomed to such radical departures from conventional storytelling. The film's explicit exploration of sexual desire and religious transgression shocked many viewers of the era, particularly given its religious subject matter. However, a small but dedicated following of artists, intellectuals, and surrealist enthusiasts embraced the film, attending multiple screenings and defending it against mainstream criticism. In the decades following its rediscovery, audience reception has become increasingly positive, with modern viewers more accustomed to non-linear narratives and surreal imagery. Today, the film is frequently screened at art houses, museums, and film festivals, where it attracts audiences interested in experimental cinema and film history. Its status as a cult classic has grown steadily, with many contemporary viewers appreciating its bold artistic vision and historical significance.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given to the film upon its release due to its controversial nature and avant-garde style

- Retrospective recognition by the Cinémathèque Française as a landmark of surrealist cinema (1960s)

- Honored at the 1975 Telluride Film Festival as part of their surrealist cinema retrospective

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Sigmund Freud's theories of psychoanalysis and dream interpretation

- André Breton's Surrealist Manifesto and surrealist artistic principles

- German Expressionist cinema's use of distorted reality and psychological themes

- Antonin Artaud's theories of the Theater of Cruelty

- French Impressionist cinema's focus on psychological states

- Symbolist poetry and literature's use of metaphor and suggestion

- Dadaist rejection of conventional artistic forms

- The psychological horror literature of Edgar Allan Poe

- The philosophical writings of Friedrich Nietzsche

- The visual art of Salvador Dalí and other surrealist painters

This Film Influenced

- Un Chien Andalou (1929) - Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí

- L'Âge d'Or (1930) - Luis Buñuel

- Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) - Maya Deren

- Eraserhead (1977) - David Lynch

- Persona (1966) - Ingmar Bergman

- 8½ (1963) - Federico Fellini

- The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) - Luis Buñuel

- Blue Velvet (1986) - David Lynch

- Mulholland Drive (2001) - David Lynch

- The Holy Mountain (1973) - Alejandro Jodorowsky

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for several decades before being rediscovered in the 1960s. Multiple copies have since been found in various European archives, including the Cinémathèque Française and the British Film Institute. The film has undergone several restoration processes, with the most comprehensive being completed in the early 2000s using digital technology to clean and stabilize the surviving prints. While some scenes remain incomplete or damaged, the film survives in a watchable condition that preserves most of its original visual impact. The restoration efforts have been crucial in maintaining the film's status as an important work of cinematic history. Current preservation status is considered good, with several high-quality versions available for scholarly and public viewing.