Undressing Extraordinary

"A Picture That Simply Convulses an Audience with Laughter"

Plot

In this early British trick film, a weary traveler enters his hotel room and attempts to undress for bed, but finds himself subjected to a series of magical costume transformations. After removing his coat and vest, he suddenly appears in a continental uniform, which when angrily discarded is replaced by a policeman's costume, then a soldier's uniform. Just as he believes he's finally free of the magical transformations and approaches his bed, he discovers a skeleton lying on his pillow. The film culminates with the bed disappearing beneath him, leaving him sitting on the floor as bedclothes rain down from above, creating a comedic spectacle of frustration and bewilderment.

Director

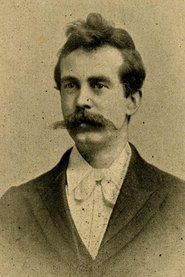

Cast

About the Production

This film was created using stop-motion substitution techniques, where the camera would be stopped, the actor would change costumes, and filming would resume to create the illusion of instantaneous transformation. The production utilized multiple props and costumes that had to be precisely positioned for each transformation sequence. The bed disappearing effect was likely achieved through a simple cut, while the falling bedclothes were probably dropped from above the frame. As with many early films, it was shot in a single take with minimal editing, requiring perfect timing and coordination from the performer.

Historical Background

Undressing Extraordinary was produced during the pioneering years of cinema when filmmakers were still discovering the medium's possibilities. 1901 was a crucial year in early cinema, with filmmakers competing to create increasingly spectacular trick films following the success of Georges Méliès's work in France. In Britain, Robert W. Paul was one of the leading producers, and Walter R. Booth was his principal director of fantasy films. This period saw the development of basic special effects techniques including stop-motion, multiple exposures, and substitution tricks. The film emerged at a time when cinema was transitioning from novelty to entertainment, with films becoming more sophisticated in their storytelling and technical execution. The early 1900s also saw the establishment of permanent cinemas, moving away from fairground and music hall exhibitions, creating a demand for more varied and engaging content.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of early British comedy and special effects cinema, demonstrating how quickly filmmakers mastered the art of cinematic illusion. It showcases the development of the trick film genre, which was crucial in establishing cinema as a medium capable of creating impossible scenarios. The film's theme of magical transformation reflects the public's fascination with spiritualism and magic that was prevalent in the Victorian era. As one of the early examples of a comedy film with a clear narrative progression, it helped establish conventions that would influence comedy filmmaking for decades. The film also demonstrates the international nature of early cinema, being produced in Britain but distributed internationally, including in the United States through Edison's company. Its preservation and continued study provide valuable insight into the technical and artistic development of cinema during its first decade.

Making Of

Walter R. Booth, who began his career as an illustrator and magician, brought his understanding of illusion to filmmaking. The production took place in Robert W. Paul's studio in London, one of Britain's first film production facilities. Booth served as both director and star, performing the frantic costume changes himself. The transformation sequences required precise timing - the camera had to be stopped, Booth would quickly change into the next costume, and filming would resume. The bedclothes falling from above were likely accomplished by having stagehands drop them from just outside the camera frame. The skeleton prop was probably positioned during one of these stops. The entire film was shot in a single day, as was typical for productions of this era, with minimal sets and props. The film's success led to Booth creating more elaborate trick films throughout the early 1900s.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Undressing Extraordinary exemplifies early single-camera technique, with the entire film shot from a fixed position to facilitate the stop-trick effects. The camera work is straightforward but effective, positioned to capture the full action within the hotel room set. The lighting is typical of early studio productions, using natural light from windows or basic artificial illumination. The frame composition carefully positions the actor and props to maximize the impact of the transformations while maintaining visual clarity. The cinematographer had to ensure consistent lighting between takes to maintain the illusion of continuous action during the substitution sequences. The camera's static position was essential for the trick effects to work seamlessly, as any movement would reveal the cuts and changes. The visual style prioritizes clarity of action over artistic composition, reflecting the functional needs of early trick films.

Innovations

Undressing Extraordinary showcases several important technical innovations of early cinema. The film's primary technical achievement is its sophisticated use of stop-trick photography, where the camera is stopped and restarted to create the illusion of instantaneous transformation. This technique required precise timing and coordination between the actor and camera operator. The film also demonstrates early understanding of continuity editing within a single shot, maintaining spatial relationships despite the magical changes. The production utilized multiple costume changes that had to be executed quickly between camera stops, showing early mastery of practical effects. The falling bedclothes sequence represents an early use of gravity-based special effects. The film's success in creating these seamless transitions helped establish substitution tricks as a fundamental special effects technique that would be used throughout cinema history. The technical execution of these effects in 1901, with crude equipment and limited means, represents a significant achievement in early filmmaking.

Music

As a silent film, Undressing Extraordinary would have been accompanied by live music during its original exhibition. The typical accompaniment would have been provided by a pianist in smaller venues or a small orchestra in larger theaters. The music would have been light and comedic, likely incorporating popular tunes of the era with improvised passages to match the on-screen action. Musical cues would emphasize the magical transformations with playful motifs and build to a crescendo during the final chaotic sequence. In some venues, sound effects might have been created manually to accompany the falling bedclothes and other actions. The Edison catalog suggested appropriate musical pieces for their films, though specific recommendations for this title are not recorded. Modern screenings typically use period-appropriate piano music or specially composed scores that capture the film's whimsical and magical nature.

Famous Quotes

A picture that simply convulses an audience with laughter

The scene opens in the bedroom of a hotel. A traveler appears, evidently a 'little worse for wear.'

Memorable Scenes

- The rapid succession of costume transformations where the traveler's clothes magically change from civilian wear to military uniforms to police attire, each transformation occurring instantly through early stop-motion effects

- The final reveal where the exhausted traveler approaches his bed only to discover a skeleton lying on his pillow, followed by the bed disappearing and bedclothes raining down from above

Did You Know?

- This film was distributed in the United States by the Edison Manufacturing Company, which is why an Edison catalog description exists for a British film

- Walter R. Booth was a former magician before becoming a filmmaker, which explains his fascination with transformation and illusion in his films

- The film showcases early use of what would become known as 'stop trick' special effects, pioneered by Georges Méliès

- At only one minute long, this was typical of films from the early 1900s, which were often shown as part of variety programs

- The film was part of Robert W. Paul's catalog of trick films that competed with similar productions from France and the United States

- Booth appeared as the actor in many of his own early films, including this one, due to the small scale of productions

- The continental uniform referenced in the description likely refers to military attire from continental Europe, possibly French or German

- This film was sometimes shown under alternate titles including 'The Extraordinary Disrobing' and 'The Magical Disrobing'

- The skeleton prop was a common element in early comedy films, representing both humor and the macabre

- The film was hand-colored in some releases, a common practice for important films of this era to increase their appeal

What Critics Said

Contemporary reception, as evidenced by the Edison catalog description, was extremely positive, with the film being described as something that 'simply convulses an audience with laughter.' Trade publications of the era praised the film's clever use of substitution tricks and its comedic timing. Modern film historians recognize Undressing Extraordinary as a significant example of early British cinema and Walter R. Booth's skill in creating magical effects. Critics note the film's sophisticated understanding of cinematic space and its effective use of the single-camera setup to create complex visual gags. The film is often cited in studies of early special effects as an example of how quickly filmmakers mastered basic transformation techniques. Current scholarship appreciates the film not just as a technical achievement but as an early example of physical comedy that would later become a staple of cinematic humor.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1901 were reportedly delighted by the film's magical transformations and comedic premise. The film was a popular attraction in music halls and early cinemas, where it was often part of mixed programs that included actuality films, other trick films, and live performances. Contemporary accounts suggest that the unexpected costume changes and the final reveal of the skeleton elicited strong reactions from viewers, many of whom had never seen such cinematic illusions before. The film's brevity and clear visual humor made it accessible to audiences of all ages and backgrounds. Its success led to increased demand for similar trick films from both British and international producers. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and early cinema festivals continue to appreciate its charm and ingenuity, though the impact of its special effects is now understood in the context of film history rather than as genuine magic.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès's trick films

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Music hall comedy acts

- Victorian fascination with spiritualism

This Film Influenced

- The '?' Motorist (1906)

- The '?' Motorist (1906)

- The Magic Sword (1901)

- An Over-Incubated Baby (1901)

- Artistic Creation (1901)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives and has been preserved by the British Film Institute and other archives. Digital copies exist and are occasionally screened at early cinema retrospectives and film festivals. The preservation quality is generally good for a film of this age, though some deterioration is evident. The film has been included in several DVD collections of early cinema and is available through some educational and archival streaming services.