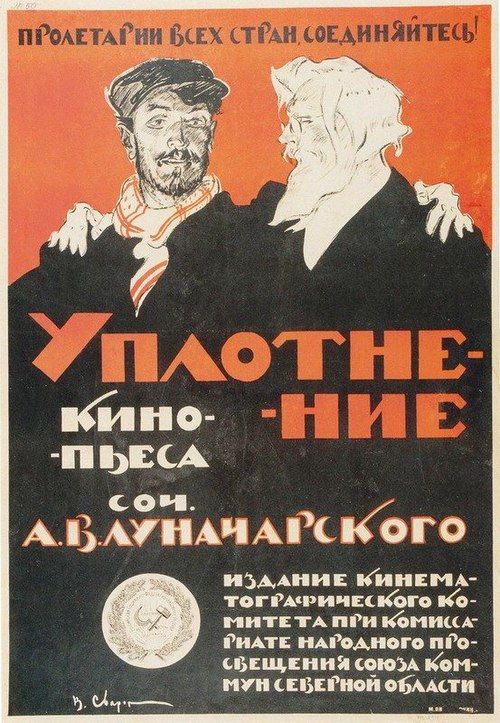

Uplotneniye

Plot

In early Soviet Russia, a professor and his daughter find their living situation transformed when workers begin attending meetings in their home, which has been modified to accommodate the new practice of housing densification. As more workers visit their residence, the professor begins delivering popular lectures at the local workers' club, bridging the gap between the intellectual and working classes. A romantic relationship develops between the professor's younger son and one of the working women who frequents their home, leading to their decision to marry. The film explores the social changes occurring in post-revolutionary Russia, where traditional class barriers are breaking down and new forms of community are emerging through shared living spaces and mutual education.

Director

Anatoli DolinovAbout the Production

Filmed during the tumultuous period of the Russian Civil War, this production faced significant challenges including resource shortages and political instability. The film was created during the early months of Soviet power when the film industry was undergoing nationalization. Director Anatoli Dolinov was among the pioneering filmmakers working to establish the foundations of Soviet cinema during this transitional period.

Historical Background

1918 was a pivotal year in Russian history, marking the first full year of Soviet rule following the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917. The country was engulfed in the Russian Civil War, with the Red Army fighting against various anti-Bolshevik forces. During this period, the Soviet government was implementing radical social and economic policies, including the nationalization of industry and the redistribution of housing. The practice of 'uplotneniye' or housing densification was part of this broader effort to address severe housing shortages and break down class distinctions by moving working-class families into the homes of the former bourgeoisie. The film industry was also undergoing transformation, with the new Soviet government beginning to exercise control over film production as a tool for propaganda and social education. Early Soviet filmmakers like Dolinov were working to establish a new cinematic language that would serve the revolutionary ideals of the new state.

Why This Film Matters

'Uplotneniye' represents an important early example of Soviet cinema's engagement with the social policies and ideological goals of the new revolutionary state. The film's focus on class reconciliation and the breaking down of social barriers reflected the core tenets of early Soviet cultural policy. As one of the earliest films to address the practice of housing densification, it provides valuable insight into how Soviet cinema attempted to normalize and promote radical social changes. The film also demonstrates the transitional nature of early Soviet cinema, which was still developing its distinctive visual style and narrative approaches that would later be perfected by filmmakers like Eisenstein and Vertov. While largely forgotten today, films like 'Uplotneniye' played a role in establishing cinema as a medium for social commentary and ideological education in the Soviet Union.

Making Of

The production of 'Uplotneniye' took place under extraordinary circumstances during the Russian Civil War. The film industry in Russia was in a state of transition, with private companies still operating but facing increasing pressure from the new Soviet authorities. Director Anatoli Dolinov worked with limited resources, as film stock and equipment were scarce during this period. The cast, primarily composed of stage actors like Ivan Lerskiy and Dmitry Leshchenko, were adapting to the new medium of cinema, which was still establishing its artistic language. The film's subject matter directly reflected the radical social changes occurring in Soviet Russia, particularly the policy of housing densification that was being implemented in major cities. The production likely faced censorship challenges as the new Soviet authorities were beginning to establish control over cultural content.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Uplotneniye' would have reflected the technical limitations and aesthetic conventions of early Soviet cinema in 1918. The film was likely shot using hand-cranked cameras with black and white film stock, which was scarce during this period. The visual style probably employed static camera positions typical of early cinema, with some use of basic tracking shots or pans as the technology allowed. Given the film's focus on domestic spaces and social interactions, the cinematography may have emphasized interior scenes that could be controlled more easily than exterior shots during the unstable conditions of the civil war. The lighting would have been rudimentary, relying primarily on natural light for exterior scenes and basic artificial lighting for interiors. While not as innovative as the later Soviet masters of montage, the film's visual approach would have served its narrative purpose of documenting social change.

Innovations

Given its early production date of 1918, 'Uplotneniye' does not appear to have introduced significant technical innovations to cinema. The film was made using the standard technology and techniques of the period, including basic editing methods and conventional camera work. However, its production during the Russian Civil War represented an achievement in itself, as the filmmakers had to overcome severe resource shortages and political instability to complete the project. The film's focus on contemporary social issues rather than historical or literary subjects demonstrated an early alignment with the Soviet preference for cinema that addressed current realities. While not technically groundbreaking, the film's existence testifies to the resilience of Russian filmmakers during one of the most turbulent periods in the country's history.

Music

As a silent film from 1918, 'Uplotneniye' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical screenings. The specific musical score is not documented, but it likely consisted of popular classical pieces or improvisations by a house pianist or small orchestra. The music would have been chosen to enhance the emotional tone of different scenes, with lighter, more romantic themes for the developing love story and more dramatic music for scenes of social transformation. Some theaters might have used pre-existing photoplay music collections that provided standardized musical cues for different emotional situations. The absence of recorded sound meant that intertitles carried the burden of conveying dialogue and narrative information, while the music provided emotional atmosphere and pacing.

Famous Quotes

In the new Russia, our homes belong not just to our families, but to the revolution itself

Knowledge is not a privilege of birth, but a tool for all workers to build our future

When walls between rooms fall, walls between hearts may follow

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where workers first enter the professor's home, representing the breaking down of class barriers; the professor's first lecture at the workers' club, showing intellectual solidarity with the working class; the romantic moment between the professor's son and the working woman, symbolizing the new social unity of revolutionary Russia

Did You Know?

- The title 'Uplotneniye' refers to the Soviet practice of 'housing densification' where multiple families were moved into single-family homes after the revolution

- This film was produced during the first year of Soviet rule, making it one of the earliest examples of Soviet cinema

- Director Anatoli Dolinov was a relatively obscure filmmaker who worked primarily in the immediate post-revolutionary period

- The film was shot on location in Moscow during the Russian Civil War, making production extremely difficult

- Only fragments of this film are believed to survive today, as many early Soviet films were lost or destroyed

- The film explores themes of class reconciliation, which was a major ideological focus of early Soviet cultural policy

- Ivan Lerskiy and Dmitry Leshchenko were stage actors who transitioned to cinema during this period

- The film was produced by the Neptun Film Company, which was one of the private companies that continued operating briefly after the revolution before being nationalized

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Uplotneniye' is difficult to ascertain due to the limited survival of reviews and critical writings from this chaotic period of Russian history. The film was likely reviewed in Soviet film publications of the time, which were beginning to establish criteria for evaluating cinema based on its ideological usefulness and artistic merit. Given the film's alignment with Soviet social policies, it probably received some positive attention from critics supportive of the revolution. However, as a relatively minor production from an obscure director, it may not have received extensive critical coverage. Modern film historians have largely overlooked 'Uplotneniye' due to its obscurity and the fragmentary nature of its survival, though specialists in early Soviet cinema may reference it when discussing the development of Soviet film language and themes in the immediate post-revolutionary period.

What Audiences Thought

The audience reception of 'Uplotneniye' in 1918 is difficult to document precisely, as detailed audience research was not conducted during this early period of Soviet cinema. The film's themes of class reconciliation and social transformation would have resonated with audiences experiencing the dramatic changes of the revolution firsthand. Working-class viewers, in particular, may have found the depiction of their growing social prominence empowering. However, the film's limited distribution and the chaotic conditions of 1918 Russia likely restricted its audience reach. The civil war context meant that many potential viewers were more concerned with immediate survival than with cinema attendance. Those who did see the film probably appreciated its reflection of contemporary social realities, though the film's artistic merits may have been secondary to its relevance to their lived experiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Early Russian literary realism

- Pre-revolutionary Russian drama

- Socialist realist ideology (early form)

- European silent cinema conventions

This Film Influenced

- Other early Soviet social dramas

- Films about housing policy in Soviet cinema

- Class reconciliation narratives in Soviet film

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be partially lost, with only fragments surviving in Russian film archives. Complete prints are not known to exist, making full restoration impossible. The surviving elements are held by the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive that preserves many early Soviet films. The fragmentary nature of the surviving material means that modern viewers cannot experience the complete narrative as originally intended. Some sequences may exist only in written descriptions or still photographs. The film's preservation status reflects the tragic loss of many early Soviet films due to neglect, deliberate destruction, or the deterioration of unstable nitrate film stock.