Upside Down; or, The Human Flies

Plot

In this early trick film, a magician takes the stage and begins his performance by producing numerous objects from his top hat, delighting the audience with his seemingly impossible feats. The magician then turns his attention to the spectators themselves, performing illusions that make them appear to defy gravity and walk on the ceiling. The audience members are shown in an inverted position, creating the illusion that they have become human flies walking upside down. The film culminates with the magician taking a bow as the amazed audience remains suspended in their impossible positions, showcasing the innovative special effects of early cinema.

Director

Cast

About the Production

This film was created using innovative camera techniques and in-camera effects. Walter R. Booth employed the use of a rotating camera or set to create the illusion of people walking upside down. The film was shot in a single continuous take with carefully choreographed movements to maintain the illusion. The production utilized the studio space at Paul's Animatograph Works, which was one of the first film studios in Britain.

Historical Background

This film was created during the very dawn of cinema in 1899, when moving pictures were still a novel attraction shown in music halls, fairgrounds, and dedicated exhibition venues. The late Victorian era was a time of rapid technological innovation and public fascination with scientific discoveries and magical illusions. Cinema itself was seen as a form of magic, and early filmmakers like Booth and Paul were essentially magicians using the new technology of film to create impossible visions. The film industry was still in its infancy, with no established studios, distribution networks, or star system. Films were typically short, silent, and accompanied by live music or narration. This period saw the development of basic film language and techniques that would become fundamental to cinema.

Why This Film Matters

Upside Down; or, The Human Flies represents an important early example of fantasy cinema and the use of special effects to create impossible scenarios. It demonstrates how quickly filmmakers moved beyond simply documenting reality to creating imaginative worlds. The film is part of the tradition of trick films that helped establish cinema as a medium for fantasy and wonder, influencing countless future filmmakers. It also shows the early development of the fantasy genre, which would become one of cinema's most popular categories. The film's use of camera tricks to defy gravity anticipated the special effects techniques that would become central to science fiction and fantasy filmmaking throughout the 20th century.

Making Of

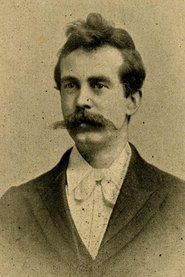

Walter R. Booth brought his background as a stage magician to this early film creation. Working at Robert W. Paul's studio in London, Booth experimented with the new medium of cinema to create illusions that were impossible on the stage. The production involved careful planning of camera angles and actor movements to maintain the upside-down illusion throughout the sequence. The actors had to perform their movements in reverse or on specially constructed sets to create the effect when the camera was inverted. The film was shot on 35mm film using Paul's own cameras and projectors, as he was both a filmmaker and equipment manufacturer. The studio setting allowed for controlled lighting and the construction of any necessary props or sets needed for the trick effects.

Visual Style

The cinematography in this film was innovative for its time, utilizing camera manipulation to create the upside-down effect. The film was likely shot using a fixed camera position with either the entire camera rig rotated 180 degrees or the action performed on a rotating platform. The lighting would have been natural or simple studio lighting, as artificial lighting technology was still primitive. The composition was carefully planned to maintain the illusion throughout the sequence. The black and white imagery was typical of the era, with the contrast helping to emphasize the impossible nature of the upside-down figures.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was the successful creation of the upside-down illusion using early camera techniques. This represented an early use of camera manipulation for special effects, predating more sophisticated techniques. The film demonstrated an understanding of how camera positioning could alter the audience's perception of reality. The smooth execution of the effect showed the growing technical proficiency of early filmmakers in controlling the medium for artistic purposes.

Music

As a silent film from 1899, there was no synchronized soundtrack. The film would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition, typically a pianist or small orchestra in the venue. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to match the magical and whimsical nature of the on-screen action. Some venues might have used popular tunes of the era or classical pieces that suited the mood of wonder and illusion.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where the entire audience appears to be walking upside down on the ceiling, creating a surreal and impossible vision that amazed early cinema viewers

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest examples of a trick film using camera manipulation to create impossible illusions

- Walter R. Booth was a former magician before becoming a filmmaker, bringing his stage experience to cinema

- The film was created just four years after the first public film screenings, making it part of cinema's pioneering era

- The 'upside down' effect was achieved by either rotating the camera 180 degrees or having the actors perform on a rotating platform

- Robert W. Paul was one of Britain's earliest film pioneers and his company produced many of the first British films

- The film was originally exhibited on Paul's Animatograph projector, which he invented and manufactured

- At only 60 seconds, this was typical of the length of films during this early period of cinema

- Booth would go on to become one of Britain's most important early fantasy and science fiction directors

- The film demonstrates the early fascination with defying natural laws that would become a staple of fantasy cinema

- This type of trick film was extremely popular with early cinema audiences who had never seen such visual illusions before

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1899 are scarce, but trade publications of the era noted the film's clever use of camera tricks and its appeal to audiences seeking novelty and wonder. The film was praised for its originality and technical innovation in creating the upside-down illusion. Modern film historians recognize it as an important early example of British fantasy cinema and a significant work in Walter R. Booth's career. Critics today view it as a valuable document of early cinematic experimentation and the development of special effects techniques.

What Audiences Thought

Early cinema audiences were reportedly delighted and amazed by the film's impossible illusions. The novelty of seeing people walk upside down was a significant draw, as audiences of the era had never experienced such visual trickery before. The film was popular in the variety theater circuit where it was typically shown alongside other short films and live performances. Audience reactions were characterized by wonder and disbelief at the magical possibilities of the new medium of cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic traditions

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- Victorian fascination with spiritualism and the supernatural

This Film Influenced

- Later trick films by Walter R. Booth

- British fantasy cinema of the early 1900s

- Physical comedy films using similar inversion techniques

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the BFI National Archive and other film archives. It has been digitized and is available for study and viewing through various archival channels. While some deterioration may exist due to the film's age and the nitrate stock it was likely shot on, efforts have been made to preserve this important early work of British cinema.