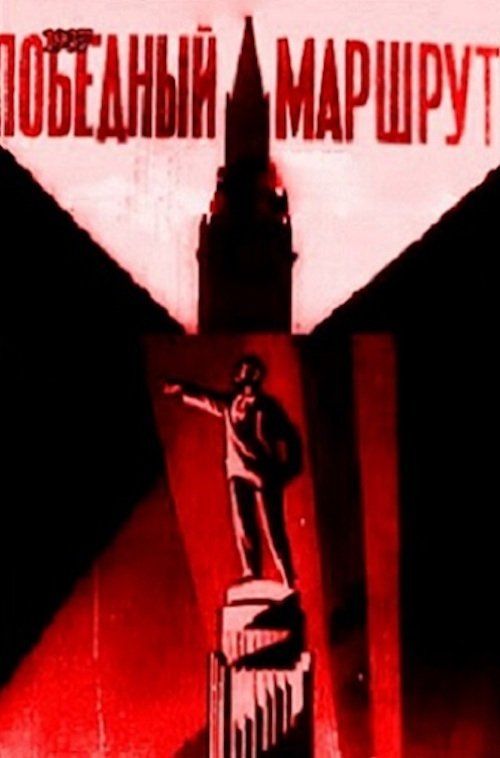

Victorious Destination

Plot

Victorious Destination is a Soviet animated propaganda short that celebrates the achievements of Stalin's five-year plans through allegorical storytelling. The film personifies the Soviet Union's industrial and agricultural progress through animated symbols and characters, showing the transformation from backward agrarian society to modern industrial powerhouse. The animation contrasts the 'old ways' with the 'new socialist future,' depicting collective farms, factories, and infrastructure projects as triumphs of the communist system. The narrative follows the journey of Soviet workers and peasants as they build socialism under Stalin's guidance, overcoming obstacles and enemies of the state along the way. The film culminates in a vision of the victorious communist future, with animated representations of Soviet achievements marching toward prosperity and glory.

Director

About the Production

Created during the height of Stalin's regime, this film was produced under strict state supervision as part of the Soviet propaganda machine. The animation team worked under the constraints of socialist realism, requiring all artistic elements to serve ideological purposes. Production would have been subject to approval by state cultural authorities, with content aligned to Communist Party messaging about the five-year plans' successes.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1939, a pivotal year in Soviet history marked by the height of Stalin's totalitarian control and the looming threat of World War II. This period saw the culmination of Stalin's purges (1936-1938), which had eliminated perceived enemies of the state and consolidated absolute power. The third five-year plan (1938-1942) was in full swing, emphasizing heavy industry and defense production in response to growing international tensions. 1939 also saw the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany, dramatically shifting the geopolitical landscape. The Soviet propaganda machine was working overtime to present an image of industrial strength, social harmony, and ideological triumph, despite the reality of forced collectivization, famine, and political terror. Animation, like all Soviet arts, was mobilized to serve these political ends, creating idealized visions of socialist achievement.

Why This Film Matters

As a product of Stalin-era propaganda, 'Victorious Destination' represents the systematic use of animation for political indoctrination in the Soviet Union. The film exemplifies how the state co-opted artistic mediums to construct and maintain ideological narratives about progress and prosperity. It contributed to the cult of personality surrounding Stalin by presenting his leadership as the driving force behind Soviet achievements. The film also demonstrates how animation was adapted to serve socialist realist aesthetics, transforming a medium often associated with entertainment into a tool for political education and mobilization. Such propaganda films played a crucial role in shaping public perception of the five-year plans, masking the human costs of rapid industrialization and collectivization with visions of inevitable triumph. The film stands as a historical artifact of how totalitarian regimes utilize popular culture to legitimize their policies and maintain social control.

Making Of

The production of 'Victorious Destination' took place within the highly controlled Soviet film industry, where every aspect of filmmaking was subject to state oversight. Director Leonid Amalrik worked with a team of animators who were required to adhere strictly to the principles of socialist realism, an artistic doctrine that demanded realistic depiction of life in its revolutionary development. The animation process would have involved traditional cel animation techniques, likely with limited resources compared to Western studios. The script and visual designs would have required approval from Glavlit, the Soviet censorship office, ensuring the film properly represented party ideology about the five-year plans. The voice work and music would have been performed by Soviet artists specializing in propaganda productions. The entire production timeline was likely compressed to meet political deadlines, as propaganda films were often commissioned to coincide with specific political events or anniversaries.

Visual Style

The visual style would have followed the principles of socialist realism applied to animation, with clean lines, bright colors, and optimistic imagery. The animation likely featured exaggerated heroic figures representing the Soviet worker and peasant, contrasted with caricatured enemies and obstacles. Industrial scenes would have been rendered with impressive scale and dynamism, emphasizing the power and progress of Soviet industry. Agricultural sequences would show bountiful collective farms, ignoring the reality of famine and resistance. The color palette would have been vibrant and uplifting, using red prominently to symbolize communism and revolution. Movement and composition would have been designed to convey energy, progress, and inevitable victory, with characters and machines moving purposefully toward their victorious destination.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking technically, the film represented the Soviet animation industry's ongoing development despite limited resources and political constraints. The animators would have worked with basic cel animation techniques, possibly experimenting with multiplane camera effects to create depth in industrial scenes. The film's technical aspects were secondary to its ideological message, but the production team would have strived for quality to properly represent Soviet achievements. The animation of machinery and industrial processes required careful study and representation, contributing to the film's educational propaganda purpose. Color technology, still relatively new in 1939, would have been used to maximum effect to create vibrant, appealing imagery that supported the film's optimistic message.

Music

The musical score would have been composed in the grand, optimistic style typical of Soviet propaganda music, likely incorporating elements of folk melodies and revolutionary songs. The soundtrack would have featured orchestral arrangements with prominent brass and percussion to convey strength and triumph. Choral elements might have been included, with massed voices singing praises of Stalin and the five-year plans. Sound effects would have emphasized industrial sounds - machinery, trains, construction - presented as music rather than noise. Any voice narration would have been delivered in the authoritative, confident tone characteristic of Soviet propaganda. The music would have been designed to evoke emotional responses of pride, optimism, and determination in Soviet audiences.

Did You Know?

- Director Leonid Amalrik was one of the pioneers of Soviet animation, known for his work on propaganda films during the Stalin era

- The film was created during the third five-year plan (1938-1942), which emphasized defense production in anticipation of war

- Soyuzdetmultfilm, the studio that likely produced this film, was specifically created for children's and educational animation but also produced propaganda

- 1939 was the year of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and Soviet propaganda of this period increasingly focused on both internal achievements and external threats

- The animation techniques used would have been relatively simple cel animation, as the Soviet industry was still developing its animation capabilities

- Propaganda films of this era were typically shown before feature films in cinemas as part of the state's cultural programming

- The film's themes align with Stalin's 1939 statement about the Soviet Union having 'completely built socialism' and moving toward communism

- Amalrik later faced criticism during the Khrushchev thaw for his Stalin-era propaganda work

- The film likely featured music by Soviet composers who specialized in patriotic and propaganda scores

- Animation studios in the 1930s USSR were heavily influenced by Disney techniques but adapted them for socialist realist content

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet reviews would have been uniformly positive, as criticism of propaganda films was impossible during Stalin's regime. State-controlled publications like Pravda and Izvestia would have praised the film for its ideological clarity and artistic merit in service of socialist construction. The film would have been evaluated primarily on its effectiveness in conveying party messages rather than artistic innovation. Modern film historians view such works primarily as historical documents, analyzing them for their propaganda techniques and what they reveal about Soviet society and politics. Western critics during the Cold War would have dismissed such films as crude propaganda, while contemporary scholars examine them within the context of totalitarian media systems and the role of animation in political communication.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences in 1939 would have received the film as part of mandatory cinema programming, with public reaction necessarily positive due to the political climate. The film's messages about industrial progress and socialist achievement would have resonated with some viewers who had indeed witnessed improvements in living standards and industrial development, though many would have been aware of the gap between propaganda and reality. The animated format would have made the political messaging more accessible and entertaining than live-action propaganda. In the repressive atmosphere of 1939, negative reactions to such films would have been dangerous to express. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives typically approach it as a historical curiosity, examining both its artistic techniques within the constraints of its time and its role in the broader Soviet propaganda effort.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Disney animation techniques (adapted for Soviet ideology)

- Socialist realist art doctrine

- Soviet propaganda poster art

- Leninist-Stalinist political theory

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet propaganda animations

- Post-war Soviet industrial films

- Cold War-era animated propaganda from both sides