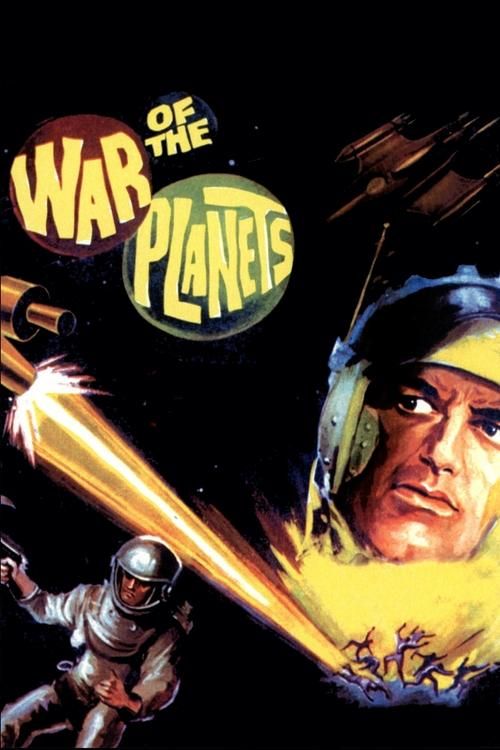

War of the Planets

"Beyond the solar system... beyond imagination... beyond hope!"

Plot

A mysterious signal from deep space disrupts all communications on Earth while a massive UFO materializes above the Antarctic waters. Captain Alex Hamilton, commanding the spaceship Orion, is dispatched with his elite crew to venture beyond the Solar System and trace the signal to its source. Their journey leads them to an uncharted alien world where they discover a terrifying reality: a colossal robot has enslaved an entire civilization of humanoid beings, systematically draining their psychic energies to power its mechanical empire. The crew must navigate political intrigue among the enslaved population while devising a plan to overthrow the mechanical tyrant and liberate the planet. As they uncover deeper conspiracies and face increasingly sophisticated robotic defenses, Hamilton and his team realize the fate of both this alien world and potentially Earth itself hangs in the balance.

About the Production

The film was shot in just three weeks on a shoestring budget, with many scenes recycled from other Italian sci-fi productions. The giant robot costume was constructed from scrap metal and automobile parts, requiring four operators inside to move it. Special effects were achieved through a combination of miniatures, stop-motion animation, and creative camera tricks. The spaceship bridge was a redressed set from a previous Italian TV series. Many of the alien costumes were repurposed from earlier Brescia productions.

Historical Background

War of the Planets emerged during a unique period in Italian cinema history when the country's film industry was desperately trying to compete with Hollywood's blockbuster era. Following the massive success of Star Wars in 1977, Italian producers rushed dozens of science fiction films into production, hoping to capitalize on the genre's sudden popularity. This film was part of a wave of low-budget Italian sci-fi that included titles like 'Star Crash' and 'The Humanoid'. The late 1970s also saw Italy experiencing significant economic challenges, with inflation and labor disputes affecting film production budgets. Despite these constraints, Italian filmmakers maintained their reputation for resourcefulness and creativity, often producing commercially viable films with minimal resources. The film reflects the Cold War anxieties of the era, particularly fears about technology and alien invasion that permeated popular culture.

Why This Film Matters

While not a critical or commercial success, War of the Planets has become a cult classic among bad movie enthusiasts and Italian sci-fi aficionados. It represents a fascinating example of transnational cinema, being an Italian production that deliberately mimicked American sci-fi tropes while maintaining distinctive European sensibilities. The film is frequently cited in retrospectives of 1970s European genre cinema as an example of how regional film industries attempted to compete with Hollywood blockbusters. Its creative use of limited resources has inspired modern low-budget filmmakers, and it has been featured in several film festivals celebrating cult and exploitation cinema. The movie also serves as a time capsule of 1970s fashion, technology, and cultural attitudes toward space exploration.

Making Of

The production was notoriously chaotic even by low-budget Italian standards. Director Alfonso Brescia was known for his breakneck shooting pace, often completing 20-30 setups per day. The cast and crew worked 16-hour days to meet the tight deadline. The special effects team, led by novice effects artist Armando Valcauda, had to invent techniques on the spot, including using Christmas lights for spaceship panels and creating laser effects by scratching directly onto the film negative. Several cast members reportedly fainted during filming due to the heat generated by the studio lighting combined with their heavy costumes. The film's score was composed by Marcello Giombini in just two days, with many tracks recycled from his earlier work. Post-production was equally rushed, with the final cut delivered to distributors just one week before the Italian premiere.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Mario Montuori, employed creative techniques to compensate for the limited budget. Extensive use of Dutch angles and dramatic lighting attempted to create visual interest in static scenes. The spaceship sequences utilized forced perspective and clever matte paintings to suggest vastness. The alien planet scenes were shot through colored filters to create an otherworldly atmosphere. Montuori often used handheld cameras during action scenes to mask the limitations of the robot costume and create a sense of urgency. The film's visual style reflects both Italian genre cinema conventions and attempts to emulate American sci-fi aesthetics.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film showcased remarkable ingenuity given its constraints. The production team developed several innovative cost-saving techniques, including using modified household appliances as futuristic props and creating alien landscapes through creative set dressing. The robot effects, while crude, employed a combination of suitmation and stop-motion animation that was ambitious for the budget level. The film's sound design creatively used everyday objects to create alien technology noises. The spaceship sequences utilized a combination of static models and moving camera work to simulate flight. These resourceful solutions have been studied by low-budget filmmakers as examples of maximizing production value with minimal resources.

Music

The electronic score was composed by Marcello Giombini, a pioneer of early electronic music in Italian cinema. The soundtrack features Moog synthesizers, early drum machines, and processed electric guitar to create a futuristic soundscape. Several musical cues were recycled from Giombini's earlier work in spaghetti westerns, re-orchestrated with electronic instruments. The main theme, with its driving rhythm and soaring synth melodies, became surprisingly popular among Italian electronic music enthusiasts. The soundtrack was released on LP in Italy in 1978 and has since been reissued on CD by cult music labels. Giombini's score is often cited as one of the film's strongest elements, successfully creating an otherworldly atmosphere despite the limited resources.

Famous Quotes

Captain Hamilton: 'In the infinite darkness of space, even the smallest light becomes a beacon of hope.'

Alien Leader: 'Your technology is primitive, but your spirit... that is something we have not seen in millennia.'

Robot: 'Resistance is illogical. Your psychic energy will be assimilated.'

Dr. Hill: 'We came seeking knowledge, but we found only the reflection of our own fears.'

Navigator: 'The signal grows stronger with every parsec. Whatever's out there, it knows we're coming.'

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic first appearance of the giant robot rising from the alien landscape, accompanied by thunderous electronic music and the enslaved population's terrified reactions

- The zero-gravity firefight aboard the spaceship where crew members use magnetic boots to navigate while fighting alien drones

- The psychic energy extraction sequence featuring swirling colored lights and pained expressions from the enslaved humanoids

- The climactic battle where Captain Hamilton confronts the robot using nothing but courage and a makeshift energy weapon

- The opening sequence showing the mysterious signal disrupting Earth's communications, told through a montage of television screens going static worldwide

Did You Know?

- The film was released in multiple international markets under at least seven different titles including 'Cosmo 2000: Battaglie negli spazi stellari' in Italy, 'War of the Robots' in the US, and 'Star Odyssey' in some territories

- Director Alfonso Brescia used the pseudonym 'Al Bradley' for international releases to make the film appear more American

- The giant robot costume was so heavy that actors could only remain inside for 5-10 minutes at a time

- Many of the spaceship models were actually modified toy kits and household items spray-painted silver

- The film was rushed into production to capitalize on the Star Wars craze, beginning filming just months after Star Wars premiered

- Several scenes featuring the alien planet were shot at an abandoned quarry outside Rome during winter, causing actors to suffer in near-freezing temperatures

- The psychic energy effects were created by filming colored smoke through a prism and superimposing the footage

- John Richardson, who played Captain Hamilton, had previously appeared in several Italian sword-and-sandal epics in the 1960s

- The film's script was written in just five days, with many dialogue scenes improvised on set

- Despite being set in space, over 80% of the film was shot on soundstages or at ground-level locations

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were overwhelmingly negative, with critics dismissing the film as a cheap Star Wars knock-off. Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera called it 'a pathetic attempt to ride the coattails of American science fiction with none of the magic or budget.' American critics were equally harsh when the film reached US shores in 1979, with Variety noting 'the special effects wouldn't pass muster in a high school production.' However, modern reassessments have been more charitable, with many critics appreciating the film's earnestness and creative problem-solving. Cult film websites like Badmovies.org have praised it as 'endearingly inept' and 'a perfect example of so-bad-it's-good cinema.' The film has developed a small but dedicated following among fans of European B-movies.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience response was lukewarm, with the film performing poorly in Italian theaters and even worse internationally. Many viewers were disappointed by the film's obvious budget limitations and derivative plot, especially when compared to Star Wars. However, over the decades, the film has gained appreciation from niche audiences who value its camp charm and historical significance as a product of its time. Midnight movie screenings in the 1980s and 1990s helped build a cult following, with fans particularly enjoying the film's unintentionally humorous dialogue and creative low-budget effects. Modern streaming platforms have introduced the film to new audiences, with many viewers appreciating it as a fun, nostalgic piece of 1970s sci-fi kitsch.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Star Wars (1977)

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

- Planet of the Apes (1968)

- Silent Running (1972)

- Italian peplum films

- Spaghetti western conventions

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Italian low-budget sci-fi productions

- Modern parody films

- Homages in cult cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in various formats with differing quality levels. The original Italian negative is believed to be stored at the Cineteca Nazionale in Rome, though it has suffered some deterioration over the decades. Several 35mm prints survive in private collections and film archives. The film has been released on DVD in multiple countries, often sourced from worn theatrical prints. In 2019, a German label conducted a 2K restoration from surviving elements, though some scenes remain damaged. No official Blu-ray release exists, though bootleg HD versions circulate among collectors. The film's soundtrack has been better preserved, with the original master tapes surviving in Giombini's personal archive.