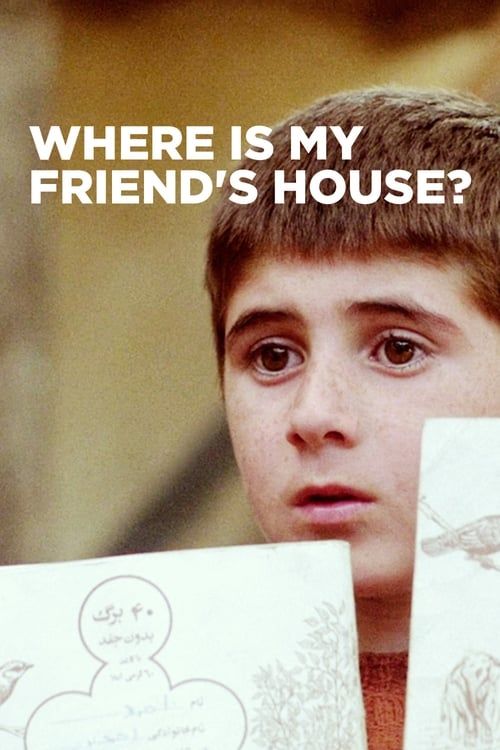

Where Is The Friend's House?

Plot

Ahmad, an 8-year-old boy in a rural Iranian village, accidentally takes his friend Mohammad Reza's notebook after school. When he discovers that his friend faces expulsion if he doesn't bring the notebook to school the next day, Ahmad embarks on a desperate quest across his village and neighboring areas to find his friend's house to return it. The simple premise unfolds into a profound journey as Ahmad encounters various obstacles and helpful strangers while navigating the adult world that often dismisses his urgent mission. His determination and moral conviction drive him through a series of increasingly frustrating encounters, highlighting themes of responsibility, friendship, and childhood innocence against the backdrop of traditional Iranian village life.

About the Production

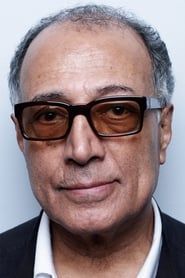

Shot with non-professional actors from the local village, with director Abbas Kiarostami employing a documentary-style approach. The film was made during the Iran-Iraq war period, which created additional production challenges. Kiarostami often improvised scenes with the child actors, allowing them to react naturally to situations rather than following a strict script. The production used minimal equipment and natural lighting to maintain authenticity.

Historical Background

The film was created during a transformative period in Iranian cinema following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The new government initially imposed strict censorship, but also established institutions like Kanoon that supported educational and children's films. The Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) was ongoing during production, creating a climate of uncertainty and limited resources. This period saw the emergence of a new wave of Iranian filmmakers who worked within constraints to create poetic, humanistic cinema that gained international attention. The film's focus on rural life and childhood innocence provided a subtle commentary on Iranian society that could pass through censorship while still carrying deeper meaning about responsibility, community, and human dignity.

Why This Film Matters

Where Is The Friend's House? revolutionized international perceptions of Iranian cinema and established Abbas Kiarostami as a master filmmaker. The film demonstrated how a simple story told with authenticity and poetic vision could transcend cultural boundaries. It became a template for minimalist storytelling in world cinema and influenced countless filmmakers globally. The movie's success helped launch the Iranian New Wave movement on the international stage, paving the way for other Iranian directors to gain recognition. Its humanistic approach and focus on universal themes through a specifically Iranian context showed how local stories could have global resonance. The film is now considered one of the most important works in cinema history, regularly appearing on greatest films lists.

Making Of

The production was marked by Kiarostami's innovative approach to working with non-professional child actors. He would often set up situations and let the children react naturally, capturing genuine emotions rather than coached performances. The director faced numerous challenges during filming, including limited resources, political restrictions, and the ongoing Iran-Iraq war. Many scenes had to be shot quickly and discreetly, with the crew sometimes having to pretend they were making a documentary to avoid suspicion. The film's authentic village setting was crucial, and Kiarostami spent months building relationships with the local community before filming began. The child actors were not given the full script to maintain their natural reactions to unfolding events.

Visual Style

The film features naturalistic cinematography by Farhad Saba, employing documentary-style techniques with handheld cameras and natural lighting. The visual approach emphasizes authenticity, with long takes that allow scenes to unfold organically. The camera often follows Ahmad from a child's eye level, creating intimacy and emphasizing his perspective within the adult world. The winding paths through the village are captured in sweeping shots that mirror the journey's emotional arc. The use of available light and real locations creates a sense of immediacy and truthfulness. The visual style avoids artificial beauty in favor of capturing the raw poetry of everyday life, with compositions that find grace in ordinary moments.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement lies in its seamless blending of documentary and fiction techniques. Kiarostami pioneered methods for working with non-professional child actors that felt completely authentic while still serving a carefully constructed narrative. The production team developed innovative approaches for low-budget filmmaking that maximized visual impact with minimal resources. The film's editing creates a rhythm that mirrors a child's sense of urgency and determination. The technical team succeeded in capturing the essence of village life without romanticizing or exploiting it. The film demonstrated how technical limitations could become artistic strengths, influencing independent filmmakers worldwide to embrace minimalism and authenticity.

Music

The film uses minimal music, relying instead on natural sounds of the village environment. When music does appear, it's subtle and often diegetic, coming from sources within the scene rather than an orchestral score. The soundtrack emphasizes ambient sounds - footsteps on dirt paths, village conversations, distant calls, and the rustling of papers. This naturalistic audio approach enhances the documentary feel of the film. The few musical moments are typically traditional Persian melodies that blend seamlessly with the environment. The deliberate absence of dramatic scoring forces viewers to focus on the visual storytelling and the emotional weight of simple actions and silences.

Famous Quotes

Where is your friend's house?

If you don't bring your notebook, you'll be expelled

I must find his house before tomorrow

Why won't anyone help me?

My friend will be punished because of me

Memorable Scenes

- Ahmad running through the winding village paths searching for his friend's house as evening approaches

- The scene where Ahmad repeatedly asks adults for directions but is consistently dismissed or misunderstood

- The emotional climax when Ahmad finally finds the correct house and returns the notebook

- The opening sequence in the classroom where the teacher's strict rules establish the stakes

- Ahmad's interaction with the elderly carpenter who tries to help him

- The final shot of Ahmad walking home, exhausted but triumphant

Did You Know?

- This is the first film in what became known as the Koker Trilogy, followed by 'And Life Goes On' (1992) and 'Through the Olive Trees' (1994)

- The film's title in Persian is 'Khane-ye doust kodjast?' which literally translates to 'Where is the friend's home?'

- Director Abbas Kiarostami discovered the lead actor Babek Ahmed Poor when he was visiting the village for another project

- The notebook that drives the plot was actually written by a real student to maintain authenticity

- Many scenes were shot with hidden cameras to capture natural reactions from villagers

- The film was initially intended as an educational movie for children but gained international recognition as art cinema

- The winding path Ahmad follows through the village was inspired by Kiarostami's own childhood experiences

- The film was banned in some countries due to political tensions with Iran during the 1980s

- Kiarostami often had to hide his camera during filming to avoid drawing attention from authorities

- The adult actor who plays Ahmad's grandfather was actually the boy's real grandfather

What Critics Said

The film received universal critical acclaim upon its international release, with critics praising its poetic simplicity, naturalistic performances, and profound emotional depth. Roger Ebert called it 'a film of enormous beauty and simplicity' and included it in his Great Movies collection. The New York Times hailed it as 'a masterpiece of humanist cinema.' French critics at Cahiers du Cinéma compared Kiarostami to directors like De Sica and Satyajit Ray. Contemporary critics continue to celebrate the film, with The Guardian placing it among the top 50 foreign language films of all time. The film's reputation has only grown over time, with modern critics appreciating its influence on independent cinema and its timeless exploration of childhood morality.

What Audiences Thought

While the film had limited commercial release due to its art house nature, it resonated deeply with audiences who discovered it through film festivals and specialized cinemas. Iranian audiences embraced the film for its authentic portrayal of village life and its celebration of childhood innocence. International audiences were moved by its universal themes and the young protagonist's determination. Over time, through home video releases and streaming platforms, the film has developed a devoted cult following. Many viewers report being profoundly affected by its emotional power and simple wisdom. The film's accessibility despite its cultural specificity has made it a beloved introduction to Iranian cinema for Western audiences.

Awards & Recognition

- Golden Leopard (Best Film) at Locarno International Film Festival 1987

- Golden Plaque at Chicago International Film Festival 1987

- Best Film at Fajr Film Festival 1987

- UNICEF Award at Cannes Film Festival 1989

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian Neorealism (particularly De Sica's 'Bicycle Thieves')

- Iranian literary traditions

- Documentary filmmaking techniques

- Persian poetry and storytelling

- Children's literature

- French New Wave observational cinema

This Film Influenced

- The Sweet Hereafter

- Children of Heaven

- The White Balloon

- Ratcatcher

- Beasts of the Southern Wild

- The Kid with a Bike

- Capernaum

- Mustang

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been well-preserved and restored by the Criterion Collection, which released a digitally restored version in 2015. The original negative is maintained in Iranian film archives. Given its cultural significance, the film has been carefully preserved by international film institutions including the Cinémathèque Française and the Museum of Modern Art. The restoration process involved cleaning the original elements and creating new digital masters to ensure the film's availability for future generations.