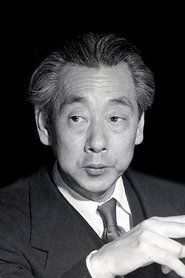

Mikio Naruse

Director

About Mikio Naruse

Mikio Naruse (1905-1969) was one of Japan's most distinguished film directors, renowned for his shomin-geki films that depicted the lives of ordinary people with profound empathy and realism. He began his career at Shochiku Studios in 1927 as an assistant director after working as a prop man and camera assistant, making his directorial debut in 1930 with the silent film 'Flunky, Work Hard.' Naruse developed a distinctive cinematic style characterized by understated drama, meticulous compositions, and a focus on the quiet struggles of women facing social and economic hardships. His breakthrough came with 'Wife! Be Like a Rose!' (1935), which became the first Japanese film to be released commercially in the United States. Despite being overshadowed internationally by contemporaries like Kurosawa and Ozu during his lifetime, Naruse created a remarkable body of work including masterpieces like 'Floating Clouds' (1955), 'Late Chrysanthemum' (1954), and 'When a Woman Ascends the Stairs' (1960). His films often explore themes of loneliness, sacrifice, and the quiet dignity of everyday life, particularly focusing on post-war Japanese society. Naruse directed 89 films during his career, though many of his early works have been lost, and today he is recognized as one of cinema's great humanists, whose influence continues to resonate in contemporary filmmaking.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Naruse's directing style is characterized by subtle realism, precise composition, and deep empathy for ordinary people. He employed a restrained, observational approach using static cameras and carefully framed shots to create emotional depth without melodrama. His technique involved elliptical storytelling, often leaving crucial moments off-screen to be inferred by viewers, and he was known for his meticulous attention to domestic details and the subtle nuances of human behavior. Naruse's visual style emphasized the constraints of physical space, often using doorways, windows, and corridors to frame his characters and reinforce their social and emotional limitations.

Milestones

- Directorial debut with 'Flunky, Work Hard' (1930)

- International breakthrough with 'Wife! Be Like a Rose!' (1935) - first Japanese film commercially released in US

- Post-war masterpieces including 'Floating Clouds' (1955)

- Venice Film Festival recognition for 'Floating Clouds' (1955)

- Berlin International Film Festival participation with 'When a Woman Ascends the Stairs' (1960)

- Complete filmography of 89 directed films

- Collaboration with actress Hideko Takamine on multiple acclaimed films

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Director for 'Sound of the Mountain' (1954)

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Director for 'Floating Clouds' (1955)

- Blue Ribbon Award for Best Director for 'Floating Clouds' (1955)

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 4th Class (1965)

Nominated

- Venice Film Festival Golden Lion for 'Floating Clouds' (1955)

- Berlin International Film Festival Golden Bear for 'When a Woman Ascends the Stairs' (1960)

Special Recognition

- Order of the Sacred Treasure from Japanese government (1965)

- Retrospectives at major international film festivals including Cannes and New York

- Named one of the greatest directors in world cinema by Sight & Sound polls

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Mikio Naruse profoundly shaped Japanese cinema's portrayal of everyday life and women's experiences, creating a body of work that serves as both artistic achievement and social document. His films captured the essence of post-war Japanese society, particularly the struggles of women navigating changing social roles and economic constraints. Naruse's influence extended beyond Japan, inspiring filmmakers worldwide with his humanistic approach and technical mastery. His emphasis on ordinary people's lives helped establish shomin-geki as a respected genre, and his films remain crucial reference points for understanding mid-20th century Japanese culture and society.

Lasting Legacy

Naruse's legacy has grown significantly since his death, with critical reevaluation placing him among the greatest directors in world cinema. His films are now regularly screened in retrospectives at major international film festivals and studied in film schools globally. The Criterion Collection has released several of his films, introducing his work to new audiences. Contemporary directors from Claire Denis to Hirokazu Kore-eda have cited Naruse as an influence, particularly his ability to find profound meaning in everyday situations. His mastery of depicting women's inner lives has made him a feminist icon in cinema studies, and his technical innovations in composition and narrative continue to influence filmmakers today.

Who They Inspired

Naruse influenced generations of filmmakers through his subtle, humanistic approach to storytelling. His impact can be seen in the works of contemporary Japanese directors like Hirokazu Kore-eda and Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who share his interest in ordinary people's lives. International directors including Claire Denis, Hou Hsiao-hsien, and Edward Yang have acknowledged his influence on their work. His techniques of elliptical storytelling and observational camera work have become standard tools in realist cinema. Naruse's focus on women's perspectives paved the way for more nuanced female representation in cinema, and his ability to convey deep emotion through minimal means continues to inspire filmmakers seeking authenticity and emotional truth.

Off Screen

Mikio Naruse led a relatively private life marked by dedication to his craft. He married actress Yuriko Hamada in 1935, but the marriage ended in divorce. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Naruse maintained a low public profile and rarely gave interviews, preferring to let his films speak for themselves. He was known for his professionalism and dedication to his work, often working long hours and maintaining exacting standards on set. Naruse never remarried and had no children, focusing his energy entirely on his filmmaking. His personal demeanor was described as quiet and modest, reflecting the understated nature of his films.

Education

No formal film education; learned through apprenticeship at Shochiku Studios starting in 1927

Family

- Yuriko Hamada (1935-1941)

Did You Know?

- Directed 89 films but only about 40 survive today due to war damage and poor preservation

- 'Wife! Be Like a Rose!' was the first Japanese film to receive a commercial theatrical release in the United States

- Often worked with the same crew for decades, creating a stable creative team

- His films were less popular in Japan than those of Kurosawa or Ozu during his lifetime

- Never won an Oscar but his films have influenced many Oscar-winning directors

- Known for his meticulous attention to detail, often spending hours setting up a single shot

- Preferred to work with natural light whenever possible

- His films often feature trains, which he used as symbols of life's journeys and separations

- Was a heavy smoker, which may have contributed to his early death from cancer

- Despite his reputation as a 'women's director,' he rarely gave interviews about his perspective on female characters

In Their Own Words

I want to portray real people, not characters. The camera should be like a window, not a mirror.

I am interested only in the present. I want to film what is happening now, in this moment.

The most important thing in film is not what you show, but what you don't show.

I don't make films about social problems. I make films about people who have social problems.

Cinema should be like life - sometimes beautiful, sometimes painful, always real.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Mikio Naruse?

Mikio Naruse was one of Japan's most acclaimed film directors, known for his realistic portrayals of ordinary people's lives, particularly focusing on women's struggles in post-war Japanese society. He directed 89 films between 1930 and 1967 and is now recognized as a master of world cinema alongside contemporaries like Kurosawa and Ozu.

What films is Mikio Naruse best known for?

Naruse is best known for 'Wife! Be Like a Rose!' (1935), his international breakthrough; 'Floating Clouds' (1955), considered his masterpiece; 'When a Woman Ascends the Stairs' (1960); 'Late Chrysanthemum' (1954); and 'Repast' (1951). These films showcase his signature style of understated realism and deep empathy for his characters.

When was Mikio Naruse born and when did he die?

Mikio Naruse was born on August 20, 1905, in Tokyo, Japan, and died on July 2, 1969, also in Tokyo, at the age of 63 from cancer. His career spanned nearly four decades from 1930 to 1967.

What awards did Mikio Naruse win?

During his lifetime, Naruse won several prestigious Japanese awards including multiple Mainichi Film Awards for Best Director and Blue Ribbon Awards. He received the Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Japanese government in 1965. His films were also recognized at major international festivals including Venice and Berlin.

What was Mikio Naruse's directing style?

Naruse's directing style was characterized by subtle realism, precise composition, and deep empathy for ordinary people. He used static cameras, careful framing, and elliptical storytelling to convey emotional depth without melodrama. His films often focused on the constraints of physical space and the quiet dignity of everyday life, particularly the struggles of women in post-war Japan.

Learn More

Films

1 film