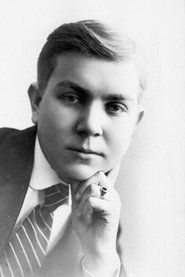

Johannes Pääsuke

Director

About Johannes Pääsuke

Johannes Pääsuke was a pioneering Estonian photographer and cinematographer who is widely regarded as the father of Estonian cinema. Born in Tartu in 1892, he began his career as a photographer before transitioning to filmmaking in the early 1910s. In 1912, he was commissioned by the Estonian Museum to document the country's cultural heritage through both photography and film, resulting in Estonia's first documentary films. His most famous work, 'Bear Hunt in Pärnumaa' (1914), is considered Estonia's first narrative film and showcases his innovative approach to storytelling. Despite his tragically brief career, spanning only from 1912 to 1918, Pääsuke produced an impressive body of work including over 1,300 photographs and several significant films that document Estonian life during a crucial historical period. His career was cut short when he died in a train accident on January 8, 1918, at the age of 26, just before Estonia's independence. Pääsuke's legacy as Estonia's first filmmaker and visual documentarian has cemented his place in the history of Baltic cinema.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Pääsuke's directing style combined observational documentary techniques with emerging narrative storytelling. He favored natural lighting and authentic locations, capturing real Estonian people in their everyday environments. His films exhibit a keen eye for composition and detail, often focusing on traditional Estonian customs, rural life, and cultural practices. Despite the technical limitations of early cinema equipment, Pääsuke demonstrated remarkable skill in creating visually compelling scenes that balanced documentary realism with dramatic elements.

Milestones

- Created Estonia's first documentary films (1912)

- Directed 'Bear Hunt in Pärnumaa' (1914), Estonia's first narrative film

- Commissioned by Estonian Museum to document cultural heritage

- Produced over 1,300 historical photographs

- Established foundational techniques for Estonian filmmaking

- Documented Estonia during transition from Russian Empire to independence

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Johannes Pääsuke Prize (established posthumously in his honor)

- Estonian Film Award for Lifetime Achievement (posthumous recognition)

Special Recognition

- Estonian Film Archive named collection after him

- Johannes Pääsuke Society established to preserve his work

- Featured in Estonian Museum of Cinematography permanent exhibition

- Commemorated on Estonian postage stamp (1992)

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Johannes Pääsuke's work represents an invaluable visual archive of Estonia during a pivotal historical period, documenting the nation's transition from imperial rule to independence. His films and photographs provide rare insights into traditional Estonian customs, rural life, and cultural practices that were rapidly changing in the early 20th century. As Estonia's first filmmaker, he established the foundation for the country's cinematic tradition and demonstrated the potential of film as both an artistic medium and a tool for cultural preservation. His documentation of Estonian life has become essential for understanding the nation's cultural heritage and has influenced generations of Estonian photographers and filmmakers.

Lasting Legacy

Johannes Pääsuke is celebrated as the father of Estonian cinema, with his work preserved in the Estonian Film Archive and displayed in museums throughout Estonia. His films, particularly 'Bear Hunt in Pärnumaa,' are considered national treasures and are regularly screened at film festivals and cultural events. The Johannes Pääsuke Society continues to research and promote his work, ensuring that his contributions to Estonian culture are not forgotten. His extensive photographic collection provides one of the most comprehensive visual records of Estonia during the early 1900s, making his work invaluable to historians, ethnographers, and cultural researchers. Pääsuke's legacy extends beyond his artistic achievements to his role in establishing Estonia's cinematic identity during the nation's formative years.

Who They Inspired

Pääsuke's pioneering work influenced subsequent generations of Estonian filmmakers by demonstrating how film could capture and preserve national culture. His approach to documentary filmmaking, emphasizing authenticity and cultural specificity, became a model for Estonian documentary tradition. His success in combining documentary observation with narrative elements inspired later Estonian directors to explore similar hybrid forms. The technical innovations he developed working with early cinema equipment helped establish practical filmmaking techniques in Estonia. His dedication to documenting Estonian culture during a period of political upheaval set a precedent for using film as a tool of cultural preservation and national identity formation.

Off Screen

Johannes Pääsuke was born into a modest family in Tartu during the period when Estonia was part of the Russian Empire. He developed an early interest in photography and visual arts, largely self-taught in the technical aspects of both photography and cinematography. His work for the Estonian Museum required extensive travel throughout Estonia, allowing him to document diverse aspects of Estonian culture and life. Pääsuke never married and had no children, dedicating his brief life entirely to his artistic pursuits. His death in a train accident near Tartu in 1918 cut short a promising career that had already made significant contributions to Estonian cultural heritage.

Education

Primarily self-taught in photography and cinematography; some formal education in Tartu but no specialized film training available during his era

Did You Know?

- Died at age 26 in a train accident, cutting short a brilliant career

- Created over 1,300 photographs in just 6 years of active work

- His films are among the earliest moving images ever made in Estonia

- Worked during Estonia's dramatic transition from Russian Empire to independent nation

- His 'Bear Hunt in Pärnumaa' is considered Estonia's first narrative film with a plot

- Much of his work was rediscovered and restored in the late 20th century

- He was both photographer and cinematographer, rare dual expertise for his time

- His films show authentic everyday life in rural Estonia before modernization

- He documented traditional Estonian customs and festivals that have since disappeared

- His work survived through the Estonian Film Archive despite political upheavals

- He used hand-cranked cameras and primitive equipment by modern standards

- His photographs are as historically valuable as his films

- He traveled extensively throughout Estonia on foot or by horse-drawn carriage

In Their Own Words

Every frame should capture the soul of Estonia and its people

The camera is our window to preserving who we are as a nation

In documenting our present, we preserve our future's past

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Johannes Pääsuke?

Johannes Pääsuke was Estonia's first filmmaker and a pioneering photographer who documented Estonian culture in the early 20th century. He is considered the father of Estonian cinema, creating the country's first documentary and narrative films before his tragic death at age 26 in 1918.

What films is Johannes Pääsuke best known for?

Pääsuke is best known for 'Bear Hunt in Pärnumaa' (1914), considered Estonia's first narrative film. Other significant works include 'The Tartu Market' (1912), 'Estonian Skiers' (1913), and 'Estonian Wedding' (1913), which are among the earliest moving images of Estonia.

When was Johannes Pääsuke born and when did he die?

Johannes Pääsuke was born on March 30, 1892, in Tartu, Estonia (then part of the Russian Empire). He died tragically in a train accident on January 8, 1918, at the age of 26, just before Estonia gained independence.

What awards did Johannes Pääsuke win?

During his lifetime, formal film awards did not exist in Estonia. Posthumously, he has been honored with the Johannes Pääsuke Prize established in his name, lifetime achievement recognition from Estonian film institutions, and his work is permanently featured in the Estonian Museum of Cinematography.

What was Johannes Pääsuke's directing style?

Pääsuke's directing style combined documentary realism with emerging narrative techniques, favoring natural lighting, authentic locations, and real Estonian people. He had a keen eye for cultural details and composition, creating films that both entertained and preserved traditional Estonian customs and rural life.

Learn More

Films

1 film