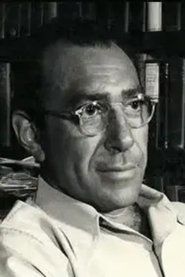

Herbert J. Biberman

Director

About Herbert J. Biberman

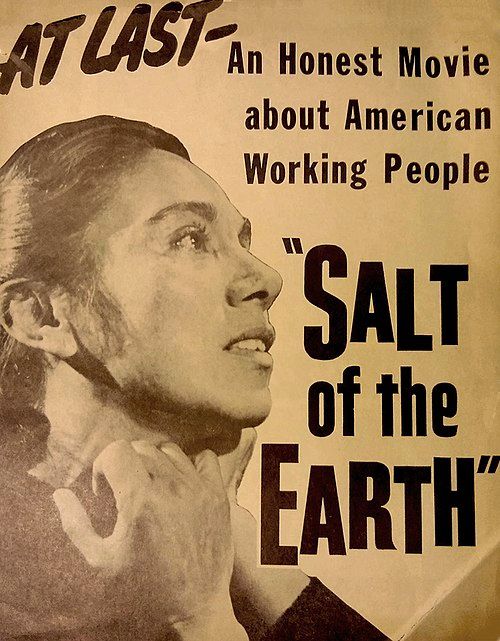

Herbert Julius Biberman was an American film director and screenwriter who became one of the most controversial and politically significant figures in Hollywood history. Born into a wealthy Philadelphia family, he began his career in theater before transitioning to film in the 1930s, directing several notable studio films including 'The Master Race' (1944). Biberman's career was dramatically altered in 1947 when he became one of the 'Hollywood Ten' - a group of entertainment industry professionals who were blacklisted for refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee. After serving a six-month prison sentence for contempt of Congress, Biberman made his most famous film 'Salt of the Earth' (1954), which was produced independently with blacklisted cast and crew and depicted a New Mexico zinc miners' strike. Despite being blacklisted itself and facing severe distribution challenges, the film became a landmark of social cinema and was eventually recognized for its artistic and social significance. Biberman continued working in independent film and television throughout the 1950s and 1960s, though his mainstream Hollywood career never recovered. His life and work exemplify the intersection of art, politics, and persecution during the Cold War era, making him a symbol of artistic resistance against political oppression.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Biberman's directing style was characterized by strong social consciousness, documentary-like realism, and a focus on working-class protagonists. He employed naturalistic acting techniques and often used non-professional or local actors to enhance authenticity. His visual approach emphasized gritty, realistic settings and compositions that highlighted social hierarchies and power dynamics. Biberman was known for his collaborative directing methods, drawing on the real-life experiences of his cast and crew, particularly in 'Salt of the Earth' where he worked closely with actual miners and their families. His films often featured long takes and mobile camera work to create immersive environments, while his editing style favored continuity and emotional resonance over flashy techniques. Thematically, Biberman consistently explored issues of labor rights, racial equality, and social justice, using cinema as a tool for political education and social change.

Milestones

- Directed 'Salt of the Earth' (1954)

- One of the Hollywood Ten blacklisted by HUAC

- Served six months in federal prison for contempt of Congress

- Pioneered independent filmmaking during the blacklist era

- Created socially conscious films focusing on labor and civil rights

- First American film to address Mexican-American workers' rights

- Mentored other blacklisted filmmakers

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- International Peace Prize (1954) for 'Salt of the Earth'

- Czechoslovakian Peace Prize (1955)

- Karoly Viski Award (Hungary, 1955)

Nominated

- Academy Award nomination for Best Story for 'The Master Race' (1944)

- Venice Film Festival Golden Lion nomination for 'Salt of the Earth' (1954)

Special Recognition

- Inducted into the Blacklist Hall of Fame (2012)

- Posthumous recognition by the Directors Guild of America for artistic courage

- Film preservation honors from the Library of Congress for 'Salt of the Earth' (1992)

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Herbert J. Biberman's cultural impact extends far beyond his filmography, representing a critical chapter in American political and cinematic history. As one of the Hollywood Ten, he became a symbol of artistic resistance against government censorship and McCarthy-era persecution. His most famous work, 'Salt of the Earth,' revolutionized independent filmmaking by demonstrating how socially relevant cinema could be produced outside the studio system. The film broke new ground by featuring Mexican-American protagonists, addressing issues of labor rights, gender equality, and racial discrimination at a time when such topics were largely taboo in mainstream American cinema. Biberman's work influenced generations of political filmmakers and documentarians, proving that cinema could serve as a powerful tool for social change. His perseverance during the blacklist era helped pave the way for greater artistic freedom in Hollywood and inspired future filmmakers to tackle controversial subjects. The restoration and preservation of 'Salt of the Earth' by the Library of Congress in 1992 cemented its status as a culturally significant work, while Biberman's life story continues to be studied as an example of courage in the face of political persecution.

Lasting Legacy

Herbert J. Biberman's legacy is that of a pioneering filmmaker who sacrificed his mainstream career for his principles, ultimately creating work of enduring social and artistic significance. His most famous film, 'Salt of the Earth,' has been recognized as one of the most important American films of the 1950s, despite being virtually unseen in the United States for decades due to political suppression. Biberman demonstrated that independent filmmaking could produce work of artistic merit that competed with studio productions, inspiring future generations of independent filmmakers. His experience as one of the Hollywood Ten contributed to the eventual dismantling of the blacklist system and served as a cautionary tale about the dangers of government interference in artistic expression. Today, Biberman is studied in film schools as an example of political cinema and artistic integrity, while 'Salt of the Earth' is frequently screened in retrospectives and academic courses about American cinema and social history. His life and work continue to inspire filmmakers who believe in cinema's power to effect social change and challenge the status quo.

Who They Inspired

Biberman influenced numerous filmmakers through his example of political courage and his innovative approach to independent filmmaking. His work prefigured the documentary-style techniques later adopted by the French New Wave and American independent cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. Directors such as John Sayles, Ken Loach, and Costa-Gavras have cited Biberman and 'Salt of the Earth' as influences on their own socially conscious filmmaking. His methods of working with non-professional actors and real communities influenced later documentary filmmakers and practitioners of cinéma vérité. Biberman's success in creating a powerful film outside the studio system during the blacklist era inspired later independent filmmakers to pursue alternative production and distribution methods. His willingness to tackle controversial political subjects paved the way for later films dealing with labor rights, civil rights, and anti-war themes. The techniques he developed for collaborative filmmaking with marginalized communities have been adopted by social documentarians and community-based filmmakers around the world.

Off Screen

Biberman was married to Academy Award-winning actress Gale Sondergaard from 1930 until his death in 1971. Their marriage endured through the blacklist period, with Sondergaard also being blacklisted for refusing to testify against her husband. The couple had two children together, Daniel and Joan. Biberman came from a wealthy Jewish family in Philadelphia, with his father owning a successful theater chain. He was known for his intellectual pursuits and political activism beyond filmmaking, participating in various left-wing organizations throughout his career. Despite the financial and professional hardships of the blacklist era, Biberman and Sondergaard maintained their home in Hollywood and continued to support other blacklisted artists. Biberman was also an accomplished writer, publishing articles about film and politics in various journals.

Education

University of Pennsylvania (attended), Columbia University (studied playwriting and directing)

Family

- Gale Sondergaard (1930-1971)

Did You Know?

- One of only two directors among the Hollywood Ten

- Served his prison sentence at the federal penitentiary in Texarkana, Texas

- 'Salt of the Earth' was the only American film to be shown in the Soviet Union in 1954

- The FBI maintained a 200+ page file on Biberman

- His wife Gale Sondergaard won an Academy Award before being blacklisted

- 'Salt of the Earth' was added to the National Film Registry in 1992

- The film's production was constantly harassed by local authorities and anti-communist groups

- Biberman had to use pseudonyms for some of his later work

- He taught film classes at UCLA after the blacklist era

- His brother Edward Biberman was a famous muralist

- The production of 'Salt of the Earth' was documented in the film 'Hollywood Ten' (1950)

In Their Own Words

I would rather betray my country than betray my friends

The blacklist is a kind of moral fascism which seeks to impose a uniformity of thought upon all Americans

Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it

We made 'Salt of the Earth' not just as a film but as an act of defiance

The only thing worse than being blacklisted is being silent

Cinema should be a weapon in the struggle for human liberation

When they took away my right to work in Hollywood, they gave me the freedom to make the films I really wanted to make

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Herbert J. Biberman?

Herbert J. Biberman was an American film director and screenwriter who became famous as one of the Hollywood Ten, a group of entertainment industry professionals blacklisted during the McCarthy era for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He is best known for directing the independent film 'Salt of the Earth' (1954), which dealt with labor rights and social justice issues.

What films is Herbert J. Biberman best known for?

Biberman is best known for 'Salt of the Earth' (1954), his landmark independent film about a New Mexico zinc miners' strike. His other notable films include 'The Master Race' (1944), 'Meet Nero Wolfe' (1936), 'New Worlds' (1938), and 'One Third of a Nation' (1939). However, 'Salt of the Earth' remains his most celebrated and influential work.

When was Herbert J. Biberman born and when did he die?

Herbert J. Biberman was born on March 4, 1900, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and died on June 30, 1971, in New York City at the age of 71. His life spanned much of the 20th century, covering the golden age of Hollywood through the turbulent political period of the 1950s.

What awards did Herbert J. Biberman win?

While Biberman received few mainstream awards due to being blacklisted, he won the International Peace Prize in 1954 for 'Salt of the Earth,' as well as the Czechoslovakian Peace Prize and the Karoly Viski Award from Hungary in 1955. His film 'Salt of the Earth' was later added to the National Film Registry in 1992, recognizing its cultural significance.

What was Herbert J. Biberman's directing style?

Biberman's directing style was characterized by social realism, documentary-like authenticity, and a focus on working-class stories. He used naturalistic acting, often casting non-professionals or local people, and employed mobile camera work to create immersive environments. His films consistently addressed themes of labor rights, social justice, and political resistance, using cinema as a tool for social change.

Why was Herbert J. Biberman blacklisted?

Biberman was blacklisted in 1947 after he and nine other Hollywood figures refused to answer questions before the House Un-American Activities Committee about their political affiliations. Citing the First Amendment, they would not state whether they were or had been members of the Communist Party. This led to convictions for contempt of Congress, prison sentences, and industry blacklisting that effectively ended their mainstream Hollywood careers.

What was the significance of 'Salt of the Earth'?

'Salt of the Earth' was historically significant as the first major American film to feature Mexican-American protagonists and address issues of labor rights, gender equality, and racial discrimination. Made independently during the blacklist era with blacklisted cast and crew, it demonstrated how socially relevant cinema could be produced outside the studio system. Despite being suppressed in the U.S. for years, it became a landmark of political cinema and was later recognized as one of the most important American films of the 1950s.

Learn More

Films

1 film