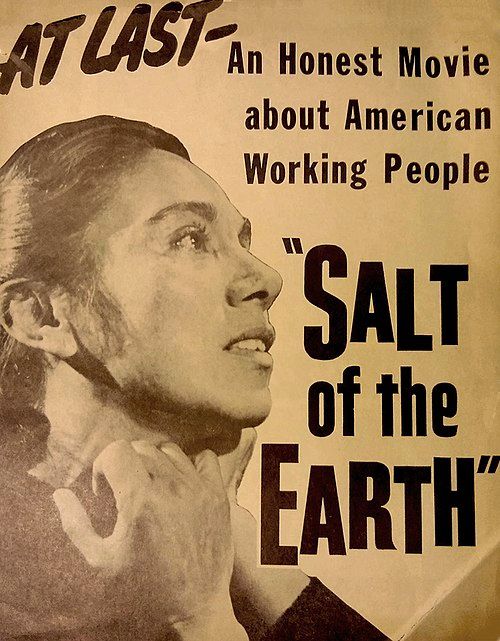

Salt of the Earth

"The film the big studios didn't want you to see!"

Plot

At New Mexico's Empire Zinc mine, Mexican-American workers led by Ramon Quintero organize a strike against dangerous working conditions and discriminatory wages that pay them less than their Anglo counterparts. The strike reveals deep-seated hypocrisies when Ramon's pregnant wife Esperanza challenges his own unfair treatment of women, demanding equality both at work and at home. When management obtains an injunction prohibiting men from picketing, the women unexpectedly take center stage, forming their own picket line while the men assume domestic responsibilities, fundamentally transforming gender dynamics in their community. As the strike intensifies, the workers face violent opposition from company thugs and local authorities, but their growing solidarity across racial and gender lines ultimately forces a confrontation with the powerful mining corporation. The film culminates in a hard-won victory that establishes not only better working conditions but also a new understanding of equality and human dignity that transcends the workplace.

About the Production

Filmed under constant FBI surveillance and local opposition; many crew members used pseudonyms; faced boycotts from local businesses; equipment was sabotaged; had to use non-union labor; filmed on location at the actual site of the 1950-1951 Empire Zinc strike; used real miners and their families as supporting actors and extras; the production was constantly harassed by local authorities and anti-communist groups.

Historical Background

'Salt of the Earth' emerged during one of the darkest periods of American political history - the McCarthy era and the Red Scare of the early 1950s. The Hollywood Blacklist had destroyed careers and silenced progressive voices in the entertainment industry. The film was based on the real 1950-1951 strike against the Empire Zinc Company in Grant County, New Mexico, a pivotal moment in labor history where Mexican-American workers demanded equal pay and safer working conditions. This strike was remarkable for its feminist dimension, as women took over picketing when men were legally prohibited from doing so. The filmmakers, all victims of the blacklist, saw in this story a parallel to their own struggle against oppression and censorship. The film's production coincided with the height of McCarthy's power, when even the mention of labor rights or racial equality could trigger accusations of communist sympathies. The fact that this film was made at all, under constant surveillance and threat, represents one of the most courageous acts of artistic resistance in American cinema history. The film's suppression and subsequent rehabilitation also mirrors the broader American journey from the paranoia of the 1950s to the social awakening of the 1960s and beyond.

Why This Film Matters

'Salt of the Earth' stands as a landmark achievement in American cinema for multiple groundbreaking reasons. It was the first major American film to feature Mexican-Americans as protagonists and to address their struggles with dignity and authenticity. The film's feminist perspective was revolutionary for its time, portraying women not as passive victims but as agents of change who challenge both corporate oppression and patriarchal traditions. Its documentary-style realism influenced generations of independent filmmakers and social issue cinema. The film's very existence as a product of blacklisted artists created a powerful narrative about artistic freedom and political resistance. Over time, it became an underground classic and a teaching tool in labor studies, women's studies, and ethnic studies programs. The film's restoration and addition to the National Film Registry helped cement its status as a crucial piece of American cultural heritage. Today, it is recognized not only as a powerful labor film but as a pioneering work in feminist cinema and an early example of what would later be called identity politics. Its influence can be seen in films from 'Norma Rae' to 'Selena' and in the work of directors like Ken Loach and John Sayles who continue to make socially conscious cinema.

Making Of

The making of 'Salt of the Earth' was itself as dramatic as the story it tells. Created by blacklisted filmmakers during the height of McCarthyism, the production faced constant harassment from government authorities and local anti-communist groups. The crew was followed by FBI agents, their equipment was frequently sabotaged, and local businesses refused to provide services. Director Herbert J. Biberman, recently released from prison for his contempt of Congress conviction, worked under enormous pressure. The casting of Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas proved problematic when she was arrested and deported mid-production, forcing creative solutions to complete her scenes. The filmmakers made the revolutionary decision to use non-professional actors from the actual mining community, with Juan Chacón, a real union organizer, playing the lead. This authenticity lent the film a documentary-like quality that would later be recognized as pioneering. The production was essentially a guerilla operation, with the crew often filming at dawn to avoid confrontations and hiding film canisters in safe houses. Despite these challenges, or perhaps because of them, the film emerged as a powerful testament to artistic resistance and social justice.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, by Stanley Kramer (not to be confused with the director-producer), employs a documentary-style realism that was groundbreaking for American narrative cinema of the 1950s. Shot in stark black and white on location in New Mexico's harsh mining landscape, the camera work emphasizes the physical reality of the workers' lives and the beauty of their environment despite its dangers. Kramer uses natural lighting and handheld techniques to create an intimate, observational quality that makes the viewer feel like a witness to real events. The framing often places characters in wide shots against the vast New Mexico sky, emphasizing their isolation and resilience. Close-ups are used sparingly but effectively, particularly in scenes of emotional confrontation, creating a powerful contrast between individual struggle and collective action. The cinematography avoids Hollywood glamour, instead presenting the characters and settings with unvarnished authenticity. The visual style draws heavily from Italian neorealism and documentary filmmaking traditions, creating a look that influenced later independent and social issue films. The decision to film at the actual strike locations and use real miners as extras adds to the visual authenticity, making the cinematography an integral part of the film's political and artistic statement.

Innovations

Despite its low budget and production challenges, 'Salt of the Earth' achieved several technical innovations that would influence independent filmmaking for decades. The film pioneered the use of non-professional actors in leading roles in American cinema, with Juan Chacón's performance setting a standard for authenticity that would later be seen in films like 'The Battle of Algiers.' The production developed innovative techniques for filming under hostile conditions, including mobile camera units that could be quickly moved to avoid interference. The sound recording team created new methods for capturing clear dialogue in outdoor industrial settings, a significant technical challenge given the noisy mining locations. The editing style, which cuts between documentary-style observation and dramatic confrontation, influenced later social realist films. The film's use of actual locations rather than studio sets was revolutionary for American cinema of the period, predating the location shooting revolution of the late 1950s and 1960s. The production also developed techniques for working with a bilingual cast and crew, ensuring authentic Spanish dialogue while maintaining accessibility for English-speaking audiences. These technical achievements were particularly remarkable given the constant surveillance and sabotage the production faced, representing not just artistic innovation but also technical ingenuity in the face of political persecution.

Music

The musical score for 'Salt of the Earth' was composed by Sol Kaplan, another blacklisted artist who brought a deep understanding of both classical composition and folk traditions to the project. The soundtrack seamlessly blends orchestral arrangements with authentic Mexican folk songs and labor anthems, creating a musical landscape that reflects the cultural heritage of the characters. Kaplan's score avoids melodrama, instead using subtle motifs to underscore the emotional and political themes of the film. The inclusion of actual workers' songs and protest music adds to the documentary feel of the production. Notably, the film features 'We Shall Not Be Moved,' a traditional protest song that becomes an anthem for the striking workers. The sound design emphasizes the industrial sounds of the mine and the natural sounds of the New Mexico landscape, creating an audio environment that grounds the story in physical reality. The music was performed by a combination of professional musicians and local community members, further blurring the line between fiction and documentary. The soundtrack received praise for its authenticity and emotional power, with critics noting how it enhanced the film's message without overwhelming the narrative. The score stands as a testament to how music can serve both artistic and political purposes in cinema.

Famous Quotes

Esperanza: 'The men are afraid. They have been beaten too many times. But I am not afraid. I have been beaten by my husband, and I am not afraid.'

Ramon Quintero: 'This strike is not just about wages. It's about dignity. It's about being treated like human beings.'

Esperanza: 'I want to be free. I want my children to be free. I want us to be free from the mine, from the company, from the men who think they own us.'

Sheriff: 'This is a peaceful community. We don't want any trouble.' Union Organizer: 'Then why do you bring guns to a peaceful protest?'

Esperanza: 'The strike has made me see that we are all fighting the same battle. The men against the company, the women against the men, and all of us against the idea that some people are worth more than others.'

Ramon: 'When I look at my wife, I don't just see a woman. I see a comrade. I see someone who is stronger than I ever knew.'

Company Manager: 'These people don't know what's good for them.' Union Organizer: 'They know what's good for their children. They know what's good for their future. That's more than you can say.'

Esperanza: 'We are the salt of the earth. Without us, the world would have no flavor.'

Memorable Scenes

- The powerful scene where the women first take over the picket line, standing together against male skepticism and company intimidation, their traditional dresses and determined faces creating an unforgettable image of feminist resistance.

- Esperanza's emotional speech to the other women about how the fight for equality at work must extend to equality at home, a scene that powerfully connects labor rights with feminist consciousness.

- The climactic victory celebration where the entire community, men and women together, march through the mining town singing 'We Shall Not Be Moved,' their faces showing both exhaustion and triumph.

- The tense confrontation between the women picketers and the company thugs, where the women's non-violent resistance ultimately overcomes violent intimidation.

- The intimate scene where Ramon and Esperanza reconcile after he recognizes her strength and leadership, representing the transformation of traditional gender roles.

- The opening sequence showing the dangerous working conditions in the mine, establishing the physical risks that motivate the strike.

- The final scene showing the integrated workforce returning to the mine under improved conditions, suggesting hope for continued progress.

Did You Know?

- Director Herbert J. Biberman was one of the 'Hollywood Ten' who were blacklisted and imprisoned for contempt of Congress after refusing to answer questions about Communist Party membership

- Lead actress Rosaura Revueltas was arrested by immigration officials during filming and deported before production was completed, forcing the filmmakers to use a double for some scenes

- The film was added to the National Film Registry in 1992 for being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant'

- The film was banned in the United States for over a decade and could only be shown in union halls, churches, and small independent theaters

- Juan Chacón, who played Ramon Quintero, was an actual union organizer and participant in the real Empire Zinc strike

- The film was financed by the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, making it one of the first films financed by a labor union

- The screenplay was written by Michael Wilson, another member of the Hollywood Ten, who had to use a pseudonym

- The film received a standing ovation at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival but was not allowed to compete in the main competition due to U.S. pressure

- The FBI maintained a surveillance file on the production throughout filming and for years afterward

- The film's title comes from the biblical phrase 'salt of the earth,' referring to the common working people

- Despite being blacklisted, the film won the International Peace Prize at the 1954 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia

- The production had to use smuggled film stock and equipment because major suppliers refused to work with the blacklisted filmmakers

What Critics Said

Upon its limited release in 1954, 'Salt of the Earth' was almost universally condemned in mainstream American press, with many critics dismissing it as communist propaganda without engaging with its artistic merits. Variety called it 'a blatant piece of Communist agitprop,' while The Hollywood Reporter denounced it as 'subversive and dangerous.' However, international critics were more receptive, with French publication Cahiers du Cinéma praising its authenticity and British critic Dilys Powell noting its 'raw power and emotional honesty.' The film's critical reputation underwent a dramatic rehabilitation during the 1960s and 1970s, as the New American Cinema movement and film studies programs rediscovered it. Andrew Sarris called it 'one of the most important American films ever made,' while Pauline Kael praised its 'unflinching honesty and emotional depth.' Modern critics universally recognize the film as a masterpiece of social realist cinema, with The New York Times' Vincent Canby later writing that 'its power has only grown with time.' The film is now studied in film schools as an example of how cinema can serve as a tool for social change while maintaining artistic integrity.

What Audiences Thought

The initial U.S. audience reception was severely limited due to the film's blacklisting and distribution challenges. When it did manage to screen, it was primarily in union halls, churches, and progressive theaters, where it received enthusiastic responses from working-class audiences and political activists. Many viewers who had experienced similar discrimination found the film deeply moving and validating. The film developed a cult following among progressive circles throughout the 1950s and 1960s, with bootleg copies circulating among activists and scholars. During the civil rights and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the film found new audiences who recognized its relevance to contemporary struggles. The Mexican-American community, in particular, embraced the film as one of the first Hollywood productions to portray their experience with authenticity and respect. Modern audiences, viewing the restored version, often express surprise at how contemporary the film's themes of gender equality and racial justice feel today. The film now regularly sells out screenings at revival theaters and film festivals, with audiences responding passionately to its emotional power and social relevance.

Awards & Recognition

- International Peace Prize, Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (1954)

- Grand Prix, International Film Festival of Locarno (1954)

- Added to National Film Registry (1992)

- National Society of Film Critics Special Citation (1970s retrospective)

- Film Heritage Award, National Society of Film Critics (1985)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian neorealism (particularly 'Bicycle Thieves' and 'Shoeshine')

- Documentary filmmaking tradition

- Soviet social realist cinema

- American social problem films of the 1930s

- Mexican cinema of the Golden Age

- Labor documentary tradition

- Federal Theatre Project productions

This Film Influenced

- 'The Battle of Algiers' (1966)

- 'Norma Rae' (1979)

- 'Matewan' (1987)

- 'El Norte' (1983)

- 'Salt of This Sea' (2008)

- 'The Full Monty' (1997)

- 'Made in Dagenham' (2010)

- 'American Dream' (1990 documentary)

- 'Harlan County, USA' (1976 documentary)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress since 1992. The film underwent a major restoration in the 1990s by the Museum of Modern Art and the American Film Institute. Original negatives were recovered from various archives and combined to create the definitive restored version. The film is also preserved in the UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Museum of Modern Art's collection. Digital restoration was completed in the 2010s, ensuring the film's availability for future generations. Despite initial suppression, multiple high-quality copies and versions exist in archives worldwide, including the British Film Institute and the Cinémathèque Française.