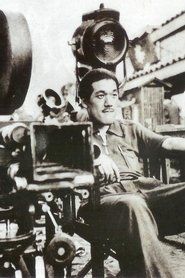

Sadao Yamanaka

Director

About Sadao Yamanaka

Sadao Yamanaka was a pioneering Japanese film director whose brief but brilliant career spanned the early 1930s until his untimely death in 1938. After joining the Makino Film Productions in 1927 as an assistant director, he quickly rose through the ranks and made his directorial debut in 1932. Yamanaka became renowned for his sophisticated jidaigeki (period dramas) that subverted genre conventions by focusing on the lives of ordinary people rather than samurai heroes. His films were characterized by their humanistic approach, social commentary, and innovative visual style that influenced generations of Japanese filmmakers. Despite directing only 22 films (many now lost), Yamanaka established himself as one of Japan's most talented directors of the 1930s. His career was cut tragically short when he was drafted into the Japanese army and died of dysentery in Manchuria at age 28, just months after completing his masterpiece 'Humanity and Paper Balloons.' His legacy as a master of cinematic storytelling continues to be celebrated by film scholars and directors worldwide.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Yamanaka's directing style was characterized by a unique blend of humanism and social realism within the jidaigeki framework. He rejected the glorification of samurai and instead focused on the struggles of common people, using long takes, naturalistic performances, and subtle visual compositions. His films often featured ensemble casts with carefully choreographed group scenes that resembled theatrical productions. Yamanaka employed innovative camera techniques for his time, including deep focus and mobile camera work, while maintaining a poetic and melancholic tone throughout his work.

Milestones

- Directorial debut with 'Dancing Village' (1932)

- Critical success with 'The Million Ryo Pot' (1935)

- Collaboration with actor Chiezo Kataoka

- Creation of 'Humanity and Paper Balloons' (1937) as his final masterpiece

- Posthumous recognition as one of Japan's greatest directors

- Influence on the Japanese New Wave movement

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Special Recognition

- Posthumous recognition by Japanese film historians as one of cinema's lost masters

- Inclusion in the Criterion Collection with restored prints

- Regular screening at international film festivals as part of Japanese cinema retrospectives

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Sadao Yamanaka's cultural impact extends far beyond his brief career and limited filmography. He revolutionized the jidaigeki genre by shifting focus from noble samurai to the struggles of ordinary citizens, thereby humanizing historical narratives and making them more relatable to contemporary audiences. His films provided subtle critiques of social hierarchy and economic inequality during Japan's militaristic period, demonstrating remarkable courage and artistic integrity. Yamanaka's work helped establish a more realistic and socially conscious approach to Japanese cinema that would influence subsequent generations of filmmakers. His tragic death at age 28 created what film historians call 'one of cinema's greatest what-ifs,' as many believe he could have become one of Japan's most important directors alongside Kurosawa and Ozu.

Lasting Legacy

Yamanaka's legacy as a master filmmaker has grown exponentially in the decades following his death, despite the loss of many of his films. 'Humanity and Paper Balloons' is now regarded as one of the greatest Japanese films ever made, regularly appearing in critics' polls and being preserved in the Criterion Collection. His innovative approach to period drama influenced the Japanese New Wave directors of the 1950s and 1960s, who admired his humanistic perspective and technical mastery. Film scholars continue to study his work as an example of how artistic vision can transcend commercial constraints and political pressures. The annual Yamanaka Sadao Award was established in his honor to recognize emerging directors who demonstrate similar artistic courage and innovation.

Who They Inspired

Yamanaka's influence on cinema is particularly remarkable given his short career. Akira Kurosawa cited him as a major influence, particularly praising his ability to blend entertainment with social commentary. His ensemble directing techniques and use of long takes prefigured the work of later masters like Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu. International directors including Martin Scorsese and Jim Jarmusch have expressed admiration for his work, with Scorsese including 'Humanity and Paper Balloons' in his personal collection of essential films. His approach to historical drama influenced not only Japanese cinema but also global perceptions of how period films can address contemporary social issues.

Off Screen

Yamanaka married actress Fujiko Yamamoto in 1936, and their marriage was cut short by his military service and subsequent death. He was known among colleagues for his intellectual approach to filmmaking and his dedication to artistic integrity over commercial success. Despite his young age, Yamanaka was respected as a mentor figure by younger directors and was part of a group of innovative filmmakers who sought to elevate Japanese cinema beyond mere entertainment.

Education

Attended Keio University but left before graduating to pursue a career in film

Family

- Fujiko Yamamoto (1936-1938)

Did You Know?

- Only 3 of his 22 films survive in complete form today

- Died of dysentery while serving in the Japanese army in Manchuria at age 28

- Was part of a group of young directors called 'Naritaki Group' who met at a bar near the Naritaki Temple

- His final film 'Humanity and Paper Balloons' was banned by Japanese military censors

- Akira Kurosawa worked as an assistant on several of Yamanaka's films

- His films were known for their unusually long takes, some lasting several minutes

- Despite his short career, he directed more films than many established directors of his era

- His wife Fujiko Yamamoto retired from acting after his death

- The restoration of his surviving films took decades due to poor storage conditions during WWII

- Contemporary critics called him 'the Japanese Chaplin' for his blend of comedy and social commentary

In Their Own Words

A film should not just show life, but reveal the truth hidden within it

The samurai sword is not as interesting as the farmer's rice bowl

I want to make films that speak to the heart of the common person

Every frame must contain both poetry and reality

The greatest drama is found in the lives of ordinary people

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Sadao Yamanaka?

Sadao Yamanaka was a brilliant Japanese film director of the 1930s who specialized in jidaigeki (period dramas). Despite directing only 22 films before his death at age 28, he is considered one of Japan's greatest cinematic masters, known for his humanistic approach and social commentary within historical settings.

What films is Sadao Yamanaka best known for?

Yamanaka is best known for 'Humanity and Paper Balloons' (1937), his final masterpiece and one of only three surviving complete films. Other notable works include 'The Million Ryo Pot' (1935), 'Kochiyama Soshun' (1936), and 'The Priest of Darkness' (1936), though many of his films are unfortunately lost.

When was Sadao Yamanaka born and when did he die?

Sadao Yamanaka was born on November 7, 1909, in Tokyo, Japan. He died tragically young on August 17, 1938, at age 28 from dysentery while serving in the Japanese army in Manchuria, just months after completing his final film.

What awards did Sadao Yamanaka win?

Yamanaka did not receive major awards during his lifetime due to his early death and the controversial nature of his work. However, he has received significant posthumous recognition, including the establishment of the Yamanaka Sadao Award in his honor and inclusion of his films in the Criterion Collection.

What was Sadao Yamanaka's directing style?

Yamanaka's directing style combined humanistic storytelling with social realism, focusing on ordinary people rather than heroic samurai. He used long takes, naturalistic performances, and ensemble casts to create poetic yet realistic portrayals of historical life, often incorporating subtle social commentary about class and injustice.

Learn More

Films

1 film