A Plantation Act

Plot

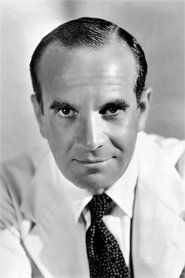

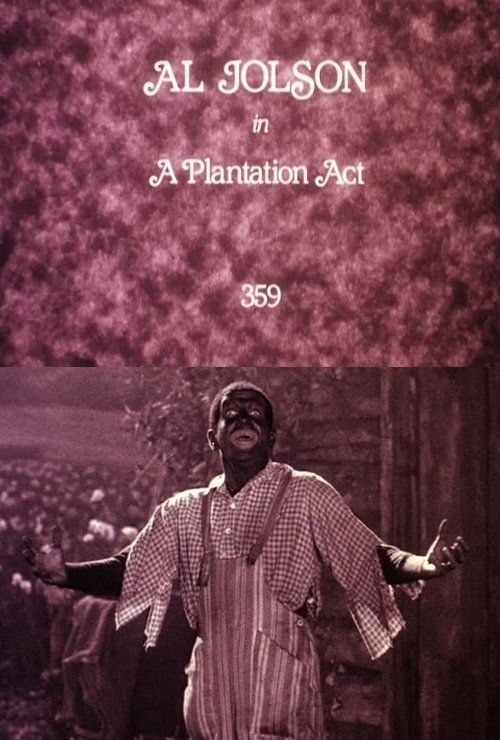

A Plantation Act is a historic Vitaphone short film featuring Al Jolson performing three of his popular songs. In this pioneering sound film, Jolson appears in blackface makeup dressed in overalls, embodying the minstrel tradition popular at the time. He performs 'When the Red, Red, Robin Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin' Along,' 'April Showers,' and 'Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody' directly to the camera with his characteristic energetic style. The film serves as a straightforward performance piece, showcasing Jolson's vocal talents and charismatic stage presence in the new medium of synchronized sound. This brief but significant short helped demonstrate the commercial viability of talking pictures to skeptical studio executives and audiences alike.

Director

Philip RoscoeCast

About the Production

Filmed using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, which required careful synchronization between the film projector and separate phonograph records. The recording was done live on set with orchestra accompaniment, as post-production dubbing was not yet possible. Jolson performed with his usual theatrical energy, which posed challenges for the primitive microphones of the era that had limited range and sensitivity. The entire production was completed in a single day, typical for these early shorts.

Historical Background

1926 was a pivotal year in cinema history, as the industry stood on the brink of the sound revolution. Silent films had reached their artistic zenith with elaborate productions and sophisticated visual storytelling, but studios were searching for new technologies to combat declining theater attendance. Warner Bros., a relatively minor studio at the time, had gambled heavily on the Vitaphone system, investing millions in sound technology while major studios like MGM and Paramount remained skeptical. The Broadway theater scene was thriving with musical revues and vaudeville acts, creating a natural synergy for bringing musical entertainment to the screen. Radio broadcasting had already accustomed the public to home entertainment, and the possibility of combining visual spectacle with synchronized sound seemed like the next logical evolution. This period also saw the rise of jazz and popular music culture, with performers like Al Jolson becoming national celebrities through recordings and stage appearances.

Why This Film Matters

'A Plantation Act' represents a crucial transitional moment in cinema history, serving as a bridge between the silent and sound eras. While not the first sound film, it was instrumental in demonstrating that popular entertainment could successfully translate to the new medium. The film's success helped convince skeptical studio executives that talking pictures were more than just a novelty, paving the way for 'The Jazz Singer' and the complete transformation of the film industry within just two years. It also marked the beginning of the end for silent cinema and the careers of many actors who could not adapt to sound. The film exemplifies the era's entertainment sensibilities, including the problematic use of blackface, which was widely accepted at the time but is now recognized as deeply offensive. Jolson's performance style and song choices reflected the popular culture of the Roaring Twenties, capturing the optimistic and exuberant spirit of the decade.

Making Of

The production of 'A Plantation Act' was a groundbreaking technical achievement that pushed the boundaries of early cinema. Warner Bros. had recently acquired the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system and was eager to demonstrate its commercial potential. The filming took place in a specially soundproofed stage at Warner Bros. Studios, where enormous microphones were hidden in various props to capture Jolson's powerful voice. The orchestra played live off-camera, with musicians carefully positioned to avoid bleeding into the vocal microphones. Jolson, accustomed to performing for live theater audiences, had to adapt his style to accommodate the technical limitations of the recording equipment. The entire process required multiple takes to achieve satisfactory synchronization between the audio and visual elements, as the technology was still in its experimental phase. The film's successful completion proved that popular entertainment could be effectively transferred to the new medium of sound cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'A Plantation Act' was necessarily static due to the technical limitations of early sound recording. The camera remained largely fixed to accommodate the large, insensitive microphones that had to be hidden in the set. Lighting was flat and even to avoid shadows that might interfere with microphone placement, resulting in a theatrical rather than cinematic appearance. The film was shot in black and white at standard silent film speed (24 frames per second), though the Vitaphone system required precise synchronization between the film and the audio discs. The visual composition was straightforward, focusing primarily on medium shots of Jolson performing, with occasional wider shots to show his full body movements. Despite these limitations, the cinematography effectively captured Jolson's charismatic performance style and provided a clear visual record of his stage presence.

Innovations

'A Plantation Act' represents a significant technical milestone as one of the first successful demonstrations of the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. The film proved that synchronized sound could be reliably achieved for commercial exhibition, overcoming the synchronization problems that had plagued earlier attempts. The recording process used large acoustic horns to capture sound, which were then mechanically transferred to wax masters for disc pressing. The system achieved remarkable frequency response for its time, capturing Jolson's voice with sufficient clarity to convey his emotional nuances. The film also demonstrated that popular entertainment could be successfully adapted to the new medium, influencing the development of the film musical genre. The technical success of this short directly contributed to Warner Bros.' decision to produce 'The Jazz Singer' as their first feature with synchronized dialogue sequences.

Music

The soundtrack consists of three songs performed by Al Jolson with orchestral accompaniment: 'When the Red, Red, Robin Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin' Along' (composed by Harry Woods), 'April Showers' (composed by Louis Silvers with lyrics by B.G. De Sylva), and 'Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody' (composed by Sam M. Lewis and Joe Young). All three songs were major hits for Jolson in his stage and recording career. The musical arrangements were adapted for film performance, with the orchestra conducted by Louis Silvers, who would later become Warner Bros.' first music director. The audio was recorded directly to Vitaphone discs using the acoustic recording process, as electrical microphones were not yet in use for film recording. The sound quality was remarkably clear for the era, though it lacked the dynamic range and frequency response of later electrical recordings.

Famous Quotes

"When the red, red robin comes bob, bob, bobbin' along, along, There'll be no more sobbin' when he starts throbbin' his old sweet song"

"Though April showers may come your way, They bring the flowers that bloom in May"

"Rock-a-bye your baby with a Dixie melody, When you croon, croon a tune from the land of cotton"

Memorable Scenes

- Jolson's energetic performance of 'When the Red, Red, Robin Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin' Along' where he breaks into his signature knee-slapping and hand-clapping routine, barely containing his theatrical exuberance within the constraints of the primitive recording equipment

- The emotional delivery of 'April Showers' where Jolson demonstrates the vocal power and sensitivity that made him a Broadway star, despite the technical limitations of early sound recording

- The finale performance of 'Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody' where Jolson fully embraces his minstrel persona, delivering the song with the charisma and showmanship that would make him a film icon

Did You Know?

- This was Al Jolson's first appearance in a sound film, predating his starring role in 'The Jazz Singer' by nearly a year

- The film was part of Warner Bros.' experimental Vitaphone program, which included shorts featuring vaudeville acts and musical performances

- Jolson's performance in this short directly led to his casting in 'The Jazz Singer', the first feature-length 'talkie'

- The film was shown as part of the first Vitaphone program at the Warner Theatre in New York, which also featured the feature film 'Don Juan' with synchronized musical score

- Only three complete copies of the film are known to survive today, preserved at the Library of Congress, UCLA Film and Television Archive, and the British Film Institute

- The Vitaphone discs for this film ran at 33 1/3 RPM, unusually slow for the era, to accommodate the longer playing time needed for the nine-minute short

- Jolson was paid $5,000 for this single day's work, equivalent to approximately $80,000 in today's currency

- The blackface makeup Jolson wore was standard for his performances at the time, though it is now widely recognized as offensive and racist

- The film's success convinced Warner Bros. to invest more heavily in sound technology, leading to their dominance in the early sound era

- The recording equipment used was so primitive that Jolson had to remain relatively stationary during his performance, limiting his usual dynamic stage movements

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were largely enthusiastic about the technical achievement of synchronized sound, with Variety praising the 'remarkable clarity' of the audio reproduction. The New York Times noted that 'the Vitaphone process adds a new dimension to motion picture entertainment,' though some critics questioned whether musical shorts would have lasting appeal. Modern critics recognize the film primarily for its historical importance rather than its artistic merit. Film historians acknowledge its role in cinema history while also critiquing the racial stereotypes it perpetuated through blackface performance. The film is now studied as an example of early sound technology and as a document of changing entertainment tastes in the 1920s.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences responded enthusiastically to 'A Plantation Act' when it premiered as part of the first Vitaphone program. The novelty of hearing a familiar voice synchronized with moving images created a sensation, with many theatergoers reporting that they felt as though they were watching a live performance. The film's success at the box office encouraged Warner Bros. to produce more Vitaphone shorts and ultimately to invest in feature-length talking pictures. Contemporary audience members were particularly impressed by the quality of the sound reproduction, which was far superior to what most had experienced through radio or phonograph records. The film helped establish Al Jolson as a major film star and demonstrated that musical entertainment had a place in the new sound cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Vaudeville theater

- Minstrel shows

- Broadway musical revues

- Radio broadcasting

This Film Influenced

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- The Singing Fool (1928)

- Say It with Songs (1929)

- Mammy (1930)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with three known complete copies existing in major archives. The Library of Congress holds a 35mm print with accompanying Vitaphone discs, while UCLA Film and Television Archive and the British Film Institute maintain additional copies. The surviving elements show some deterioration but remain viewable. The Vitaphone discs are particularly fragile, with some surface noise present but the audio content largely intact. The film has been digitally restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive in collaboration with Warner Bros., ensuring its preservation for future generations. Some original elements remain lost, including outtakes and alternative takes that may have been filmed during production.