Amangeldy

"The epic saga of Kazakhstan's fight for freedom"

Plot

Set in 1916 during the final years of the Russian Empire, 'Amangeldy' chronicles the historic uprising of Kazakh people against Tsarist oppression. When a new Russian governor arrives in the Kazakhstan steppes and attempts to impose mandatory military service on the native Kazakh population, it sparks widespread resistance among the local tribes. The film follows the journey of Amangeldy Imanov, a charismatic Kazakh leader who emerges to organize and lead the rebellion against colonial rule. As the uprising gains momentum, Amangeldy strategically allies with the Bolsheviks, recognizing their shared opposition to the Tsarist regime, while simultaneously confronting Kazakh clans who remain loyal to the Russian Empire. The narrative culminates in a dramatic confrontation that symbolizes the broader revolutionary transformation sweeping across Central Asia during this pivotal historical period.

Director

About the Production

The film was one of the earliest major Soviet productions to focus on Kazakh history and was made during Stalin's regime, which heavily influenced its portrayal of the Bolsheviks as liberators. Director Moisei Levin worked closely with Kazakh cultural advisors to ensure authenticity in costumes, customs, and language. The production faced significant challenges filming in the harsh steppe environment, with extreme weather conditions affecting both cast and crew. The film employed hundreds of local Kazakh extras, many of whom were descendants of actual participants in the 1916 uprising.

Historical Background

Produced in 1938, 'Amangeldy' emerged during one of the most turbulent periods in Soviet history - the height of Stalin's Great Purge. The film was created as part of the Soviet Union's cultural policy to showcase the 'friendship of peoples' within the socialist state while promoting the narrative that the Bolsheviks liberated oppressed nationalities from Tsarist imperialism. The historical events depicted - the 1916 Central Asian uprising against conscription into the Imperial Russian Army - were reinterpreted through a Soviet lens to emphasize the inevitability of socialist revolution. The film's production coincided with increased Russification policies, yet paradoxically also with efforts to promote national cultures under strict ideological control. This period saw the establishment of national film studios, including Kazakhfilm, which co-produced this movie. The film's release came just before World War II, when Soviet cinema was increasingly mobilized for propaganda purposes. The portrayal of Amangeldy's alliance with the Bolsheviks reflected contemporary Soviet historiography that sought to integrate national liberation movements into the broader narrative of the October Revolution.

Why This Film Matters

'Amangeldy' holds a seminal place in both Kazakh and Soviet cinema history as one of the first major feature films to center on Kazakh historical heroes and culture. The film established many conventions for subsequent Soviet national cinema, particularly in its approach to adapting historical epics for ideological purposes. It helped create a visual language for representing Central Asian peoples in film, balancing ethnographic authenticity with Soviet artistic standards. The movie played a crucial role in shaping Kazakh national identity within the Soviet framework, presenting a version of history that celebrated local resistance to oppression while ultimately aligning with Soviet revolutionary ideals. For many Kazakhs, this was their first opportunity to see their history and culture represented on the big screen, making it a landmark in cultural visibility. The film's success paved the way for more productions focusing on non-Russian Soviet peoples, contributing to the development of distinct national film industries within the USSR. Its portrayal of traditional Kazakh life, from horseback riding techniques to musical traditions, served as a cultural preservation effort even as it adapted these elements for ideological purposes.

Making Of

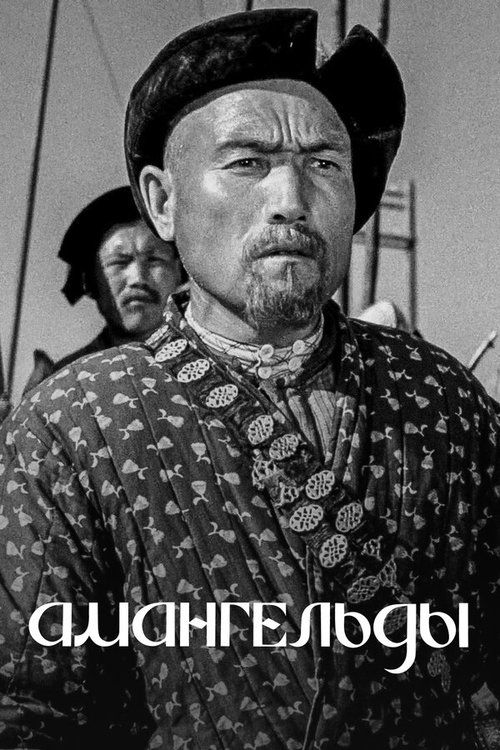

The production of 'Amangeldy' was a monumental undertaking for Soviet cinema in 1938, representing both technical and political challenges. Director Moisei Levin, a Russian filmmaker, had to navigate complex cultural sensitivities while working with Kazakh performers and crew. The casting process was particularly unique - the lead role went to Yeleubai Umurzakov, a cultural figure rather than a trained actor, chosen for his physical resemblance to the historical Amangeldy and his status within the Kazakh community. The film crew spent months in the Kazakhstan steppes, enduring extreme temperatures and logistical difficulties to capture authentic landscapes. Soviet authorities closely monitored the production to ensure it aligned with Communist ideology while still celebrating Kazakh national identity. The battle sequences involved coordinating hundreds of horsemen, many of whom were local villagers with no previous film experience. The production team also worked with ethnographers to recreate period-accurate costumes, weapons, and customs, making the film an important cultural document as well as entertainment.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Amangeldy' was groundbreaking for its time, particularly in its use of the vast Kazakhstan steppe as both setting and character. Director of photography Boris Hrennikov employed wide-angle lenses and sweeping camera movements to capture the epic scale of the landscape, creating a visual language that emphasized both the freedom and isolation of steppe life. The film utilized natural lighting extensively, particularly in outdoor scenes, to enhance the authentic feel of the historical setting. The battle sequences featured innovative camera techniques for the period, including tracking shots mounted on horseback to create dynamic action sequences. The visual contrast between the open steppe and the confined Russian administrative buildings served as a powerful metaphor for the film's themes of freedom versus oppression. The black and white photography made effective use of shadow and light, particularly in night scenes of secret revolutionary meetings. Costume and production design were meticulously researched, with traditional Kazakh clothing and architecture recreated in detail, contributing to the film's ethnographic value as well as its artistic merit.

Innovations

For its time, 'Amangeldy' represented several significant technical achievements in Soviet filmmaking. The production pioneered new techniques for filming in extreme steppe conditions, developing specialized equipment to protect cameras from dust, wind, and temperature variations. The battle sequences featured some of the most complex coordinated action scenes in Soviet cinema up to that point, involving hundreds of horsemen and requiring innovative approaches to staging and filming large-scale movement. The film's sound recording was particularly challenging due to the outdoor locations and need to capture authentic ambient sounds of the steppe environment. The production team developed portable sound equipment that could withstand field conditions while maintaining audio quality. The film also made advances in makeup and costume design for portraying Central Asian peoples authentically, moving away from the caricatured representations common in earlier Soviet films. The editing techniques, particularly in the action sequences, were innovative for their use of cross-cutting between different narrative threads to build tension and dramatic effect. The film's preservation and restoration in the 1970s also contributed to developing techniques for salvaging damaged nitrate film stock, methods that would benefit other historical Soviet films.

Music

The musical score of 'Amangeldy' was a pioneering fusion of traditional Kazakh folk music with Soviet classical composition techniques. Composer Vasily Velikanov worked closely with Kazakh folk musicians to incorporate authentic instruments such as the dombra (two-stringed lute), kobyz (bow instrument), and sybyzgy (flute) into the orchestral arrangements. The soundtrack featured several traditional Kazakh folk songs, some performed by Yeleubai Umurzakov himself, adding cultural authenticity to the production. The musical themes were carefully crafted to support the film's narrative arc, with heroic motifs for Amangeldy, oppressive themes for the Tsarist authorities, and triumphant revolutionary music for the Bolshevik alliance. The score avoided the typical bombastic style of many Soviet propaganda films, instead opting for more nuanced and culturally specific musical expressions. The recording process presented unique challenges, as traditional Kazakh instruments had to be balanced with Western orchestral instruments in studio conditions unfamiliar to the folk musicians. The resulting soundtrack was influential in establishing a template for subsequent Soviet national films seeking to balance local musical traditions with socialist realist aesthetic requirements.

Famous Quotes

The steppe belongs to those who ride it, not to those who try to fence it.

When the Tsar takes your sons for his wars, he takes your future as well.

A people without freedom are like horses without the wind to run in.

Our ancestors fought for this land, and we will fight for it too.

The Bolsheviks may be strangers, but the Tsar is our enemy.

Freedom is not given, it is taken with blood and courage.

Today we ride for our people, tomorrow for all peoples.

The steppe remembers those who fight for her, and forgets those who betray her.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the vast Kazakhstan steppe with traditional horsemen riding across the horizon, establishing both the setting and the cultural context

- The tense confrontation scene where Amangeldy faces the Russian governor and refuses conscription orders, symbolizing the spark of rebellion

- The massive battle sequence where hundreds of Kazakh horsemen attack the Russian fortress, filmed with innovative camera techniques that emphasized both the scale and chaos of the uprising

- The night meeting scene where Amangeldy decides to ally with the Bolshevik representatives, showing the strategic political maneuvering behind the rebellion

- The final standoff between Amangeldy's forces and the Tsar loyalists, culminating in a dramatic horse chase across the steppe at sunset

- The scene where traditional Kazakh musicians perform revolutionary songs, blending cultural heritage with political messaging

Did You Know?

- Yeleubai Umurzakov, who played Amangeldy, was not a professional actor but a respected Kazakh poet and folk singer chosen for his authentic appearance and cultural significance

- The film was commissioned as part of Stalin's policy of promoting national cultures within the Soviet framework, known as 'korenizatsiya' (indigenization)

- Real descendants of Amangeldy Imanov served as historical consultants during filming

- The battle scenes were filmed using actual Kazakh horsemen who maintained traditional riding techniques

- The film was briefly banned in 1941 during the Nazi-Soviet pact period due to its anti-imperialist themes

- Director Moisei Levin later faced political persecution during Stalin's purges despite the film's success

- The original film negative was partially damaged during World War II but was later restored in the 1970s

- The film's premiere in Almaty (then Alma-Ata) drew over 10,000 viewers, a record for the region at the time

- Traditional Kazakh musical instruments were used in the score rather than standard Soviet orchestral arrangements

- The film was one of the first to feature the Kazakh language prominently in a Soviet production

What Critics Said

Upon its release in 1938, 'Amangeldy' received generally positive reviews from Soviet critics, who praised its epic scope, authentic representation of Kazakh culture, and alignment with socialist realist principles. Pravda and other official Soviet newspapers highlighted the film's successful portrayal of the 'historical friendship' between Kazakh people and Russian revolutionaries. Critics particularly commended Yeleubai Umurzakov's performance as Amangeldy, noting his natural charisma and authenticity despite his lack of professional acting experience. The film's cinematography and use of the vast steppe landscapes were also widely praised as technical achievements. However, some contemporary critics noted that the film occasionally struggled to balance historical accuracy with ideological requirements, particularly in its depiction of the Bolsheviks' role in the uprising. In later decades, film historians have reevaluated 'Amangeldy' as both a significant artistic achievement and a product of its political time, acknowledging its technical merits while critiquing its historical revisionism. Modern Kazakh scholars have complex views, recognizing the film's role in preserving cultural elements while questioning its political messaging.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular among Soviet audiences, particularly in Central Asian republics where it drew record crowds. In Kazakhstan, the premiere events became major cultural celebrations, with many viewers attending multiple screenings. Kazakh audiences responded especially positively to seeing their language, traditions, and landscape featured prominently in a major production. The film's action sequences and dramatic portrayal of national resistance resonated strongly with viewers across the Soviet Union. However, some older Kazakhs who remembered the actual 1916 events noted discrepancies between the film's portrayal and historical reality, particularly regarding the role of the Bolsheviks. Despite this, the film became a cultural touchstone for generations of Soviet citizens, with Amangeldy becoming a familiar heroic figure. The movie continued to be shown in Soviet cinemas and television for decades, becoming part of the official cultural curriculum. In post-Soviet Kazakhstan, the film maintains a nostalgic appeal, though younger audiences often view it through a more critical lens regarding its historical accuracy and political messaging.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (Second Class) - 1939

- Order of the Red Banner of Labor awarded to director Moisei Levin - 1939

- Kazakh SSR State Prize - 1939

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Sergei Eisenstein's 'Alexander Nevsky' (1938) - for its approach to historical epic and national heroism

- Vsevolod Pudovkin's 'The End of St. Petersburg' (1927) - for its revolutionary themes

- Traditional Kazakh oral epics and folk tales

- Soviet socialist realist artistic doctrine

- John Ford's westerns - for their use of landscape as narrative element

- Historical paintings of the 19th century Russian school

This Film Influenced

- Taras Bulba (1962) - for its portrayal of national resistance

- The White Sun of the Desert (1970) - for its Central Asian setting and revolutionary themes

- Later Kazakh historical epics of the Soviet period

- Post-Soviet Kazakh films about national history

- Other Soviet 'national cinema' productions of the 1940s-1950s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original nitrate film stock suffered damage during World War II when parts of the Lenfilm archives were temporarily evacuated. However, the film was successfully restored in the 1972-1973 period by Soviet film preservationists using advanced techniques for the time. A complete 35mm copy exists in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow, and digital restorations have been completed in the 2010s as part of efforts to preserve Soviet cinema heritage. The film is considered well-preserved for its age, with both Russian and Kazakh language versions available. Some original outtakes and behind-the-scenes footage have been discovered and preserved in recent years, adding to the historical documentation of this significant production.