Big Business

Plot

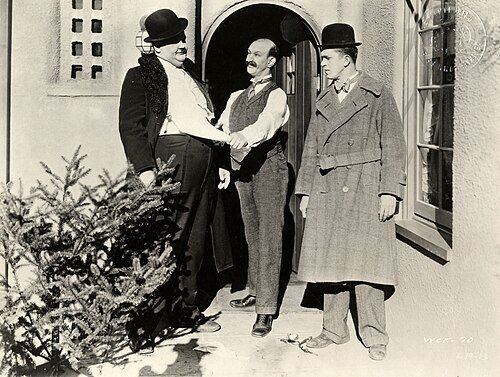

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy play door-to-door Christmas tree salesmen in California during the holiday season. Their attempts to sell a tree to the perpetually grumpy James Finlayson escalate into an increasingly destructive feud when Finlayson refuses to buy. What begins as simple salesmanship devolves into a symphony of destruction as both sides retaliate, with Finlayson's home and the boys' car suffering progressive damage. The conflict reaches its climax when both the house and vehicle are completely destroyed in a comedic crescendo of mutual annihilation. The film ends with the classic Laurel and Hardy touch of ironic resolution as both parties stand amidst the rubble of their own making.

Director

About the Production

This was one of Laurel and Hardy's first sound films, though it was originally conceived as a silent. The film was shot during the transitional period between silent and sound cinema, requiring careful consideration of audio effects for the destruction sequences. The Christmas tree sales premise was reportedly inspired by actual door-to-door salesmen common during the Depression era. The production team had to secure multiple houses and cars for filming due to the extensive destruction required for the escalating comedy sequences.

Historical Background

Released in April 1929, 'Big Business' emerged during a pivotal moment in American history and cinema. The film debuted just months before the stock market crash of October 1929 that would trigger the Great Depression, making its themes of struggling salesmen particularly resonant. The movie industry itself was undergoing massive technological change with the transition from silent to sound films, a transition that Laurel and Hardy navigated successfully while many other stars faltered. This period also saw the rise of the studio system, with Hal Roach Studios establishing itself as a premier comedy production house. The film's release coincided with the peak popularity of short subjects in theaters, before the double-feature system would eventually diminish their importance.

Why This Film Matters

'Big Business' represents a pinnacle of silent-to-sound era comedy and has influenced countless filmmakers and comedians. The film's perfect structure of escalating conflict and destruction has been studied and emulated in comedy for decades. It exemplifies the golden age of physical comedy, where timing and visual storytelling transcended the need for dialogue. The movie's preservation in the National Film Registry underscores its cultural importance as a representative work of American comedy. Laurel and Hardy's chemistry in this film established them as one of cinema's greatest comedy teams, influencing later duos from Abbott and Costello to modern comedy pairs. The film's themes of consumerism and conflict remain relevant, making it a timeless piece of social commentary disguised as slapstick comedy.

Making Of

The production of 'Big Business' took place during Hollywood's challenging transition from silent to sound films. Director James W. Horne, who had extensive experience with both silent and sound comedy, masterfully balanced visual gags with emerging sound technology. The film's destruction sequences required meticulous planning and multiple takes, as each level of damage had to be progressively worse than the last. The Christmas tree sales premise was developed by Laurel and Hardy themselves during brainstorming sessions at Hal Roach Studios. The film's success led to it being used as a training tool for new comedy directors at MGM, demonstrating perfect pacing and escalation of physical comedy. The production team had to work closely with local authorities to ensure the destruction sequences could be filmed safely without causing actual damage to private property.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Stevens employs careful framing to maximize the comedy of the destruction sequences. The camera work maintains clear sightlines throughout the escalating chaos, ensuring audiences can follow every gag. Stevens uses medium shots effectively to capture both the performers' reactions and the growing destruction. The film's visual composition demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of spatial relationships, crucial for the physical comedy. The cinematography balances wide shots showing the scale of destruction with close-ups capturing Laurel and Hardy's priceless expressions. The lighting remains consistent throughout, creating a bright, cheerful atmosphere that contrasts humorously with the increasing violence of the action.

Innovations

As one of the early sound comedies, 'Big Business' demonstrated technical mastery in synchronizing sound effects with physical comedy. The film's destruction sequences required innovative camera techniques and editing to maintain continuity across multiple takes. The production team developed new methods for safely executing destruction gags on set, techniques that would influence later action and comedy films. The sound mixing for the various crashes and impacts was groundbreaking for its time, creating a rich audio landscape that enhanced the visual comedy. The film's perfect pacing, achieved through precise editing, set a standard for comedy timing that would influence filmmakers for decades. The successful integration of sound with established silent comedy techniques represented a significant technical achievement in early cinema.

Music

The film features a synchronized musical score composed by Leroy Shield, who created many memorable themes for Hal Roach productions. The music enhances the comedy without overwhelming the visual gags, using leitmotifs for different characters and situations. Sound effects were carefully timed to match the destruction sequences, with each crash and bang punctuated perfectly. The score includes variations of the popular 'Dance of the Cuckoos' theme that would become associated with Laurel and Hardy. The music transitions from cheerful and optimistic during the opening scenes to increasingly frantic as the destruction escalates. The soundtrack represents an early successful example of music and sound effects enhancing rather than detracting from visual comedy.

Famous Quotes

Stan Laurel: 'You know, Ollie, I was just thinking...'

Oliver Hardy: 'Well, here's another nice mess you've gotten me into!'

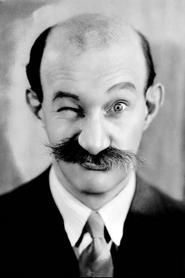

James Finlayson: [Various frustrated grunts and exclamations throughout the film]

Stan Laurel: 'This is a fine pickle you've gotten us into!'

Oliver Hardy: 'Why don't you do something to help?'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Stan and Ollie attempt to carry an oversized Christmas tree to Finlayson's door, struggling with its bulk and constantly getting tangled

- The moment when Finlayson first refuses to buy the tree, setting off the chain reaction of escalating revenge

- The systematic destruction of Finlayson's house, including the famous scene where Ollie methodically breaks every window

- The reciprocal destruction of Stan and Ollie's car, with Finlayson using increasingly creative methods to damage the vehicle

- The final shot where both parties stand amidst the complete wreckage of their respective properties, having achieved mutual annihilation

Did You Know?

- This film is considered one of Laurel and Hardy's greatest works and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1992

- The film was shot in just three days, a remarkably short time considering the complex destruction sequences

- James Finlayson's character was named 'Mr. Piedmont' in the script, though his name is never mentioned in the film

- The Christmas tree that Laurel and Hardy try to sell was actually a real tree that had to be replaced multiple times during filming

- This was one of the first Laurel and Hardy films to be released with a synchronized musical score and sound effects

- The house destruction sequence required three different houses and extensive miniature work for certain shots

- The film's escalating destruction formula became a template for many later comedy films

- Stan Laurel reportedly broke his finger during one of the destruction takes but continued filming

- The car used in the film was actually purchased specifically for destruction scenes

- This short film was often paired with feature films in theaters as part of double bills

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Big Business' as a masterpiece of comedy construction, with many reviews highlighting its perfect pacing and escalating humor. The film was lauded for successfully transitioning Laurel and Hardy's comedy style to sound without losing the visual gags that made them famous. Modern critics consistently rank it among the greatest comedy shorts ever made, with particular praise for its flawless structure and the team's performance. The New York Times review from 1929 called it 'a perfect example of screen comedy at its finest.' Film historian Leonard Maltin has described it as 'flawless' and 'one of the greatest comedy shorts ever filmed.' The film maintains a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on critical reviews, cementing its status as a critically acclaimed classic.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 overwhelmingly embraced 'Big Business,' with theaters reporting enthusiastic responses and frequent requests for repeat showings. The film's relatable premise of door-to-door salesmen resonated with Depression-era audiences, though it was released just before the economic collapse. The destruction sequences elicited huge laughs from audiences, who appreciated the cathartic release of seeing property destroyed in a controlled, comedic context. Modern audiences continue to discover the film through revival screenings and home video, with many considering it a gateway to classic comedy. The film's availability on various streaming platforms has introduced it to new generations, maintaining its popularity nearly a century after its release. Fan clubs dedicated to Laurel and Hardy consistently rank 'Big Business' among their top favorite films.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The work of Charlie Chaplin

- Harold Lloyd's comedy of escalation

- Buster Keaton's engineering gags

- Mack Sennett's slapstick traditions

- Commedia dell'arte character archetypes

This Film Influenced

- The Three Stooges' destructive shorts

- Jerry Lewis's physical comedy films

- The Blues Brothers' car destruction sequences

- Home Alone's trap sequences

- Jackass: The Movie's destruction gags

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress as part of the National Film Registry since 1992. Multiple high-quality prints exist in various archives, including the UCLA Film and Television Archive and The Museum of Modern Art. The film has undergone digital restoration for home video releases, with careful attention paid to both visual and audio elements. No scenes are known to be lost, and the film survives in its complete original form. The preservation efforts have ensured that this classic comedy remains accessible to future generations.