Der Jongleur

Plot

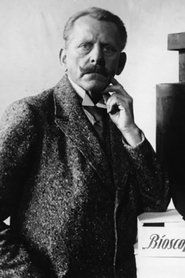

In this pioneering German short film, renowned performer Sylvester Schäffer Sr. demonstrates his remarkable juggling skills on a theater stage. The camera captures his intricate balancing act as he skillfully manipulates a bowler hat and a billiards ball, keeping them in perfect equilibrium on various parts of his body including his arms and head. Schäffer performs with the practiced confidence of a seasoned vaudeville entertainer, showcasing the kind of variety act that was popular in theaters of the late 19th century. The simple yet mesmerizing performance exemplifies the early cinema's fascination with capturing real-life spectacles and skilled performances that audiences might otherwise only see live in person.

Director

About the Production

Filmed using the Skladanowsky brothers' own Bioscop camera, which used a loop of 54mm film and could capture images at approximately 16 frames per second. The film was shot in a simple indoor setting, likely in a theater or studio space in Berlin. The Skladanowsky brothers had to develop their own film stock and processing techniques as the film industry was virtually non-existent. The entire production would have taken only a few minutes to film given the extreme brevity of early films.

Historical Background

1895 was the birth year of cinema, with multiple pioneers working simultaneously across Europe and America to develop motion picture technology. In Germany, the Skladanowsky brothers were racing against competitors to perfect their Bioscop system. This period saw the transition from optical toys like the zoetrope to true motion pictures. The Industrial Revolution had created the technological foundation for cinema, including photography, flexible film stock, and projection systems. Urbanization and the rise of a middle class with disposable income created audiences hungry for new forms of entertainment. Vaudeville and variety theaters were at their peak, and early cinema often captured these popular acts. The year 1895 also saw the first public film screenings by the Lumière brothers in Paris (December 28) and the Skladanowsky brothers in Berlin (November 1), marking the beginning of cinema as a public entertainment medium.

Why This Film Matters

'Der Jongleur' represents a crucial moment in the birth of German cinema and the global development of motion pictures. As one of the first films ever made, it demonstrates cinema's initial role as a medium for capturing and preserving theatrical performances that might otherwise be lost to time. The film is part of the very first public film screening in Germany, making it historically significant for establishing cinema as a legitimate form of entertainment in the country. It also shows how early filmmakers gravitated toward documenting skilled performers and spectacle, establishing a pattern that would continue throughout cinema history. The film's existence proves that German cinema developed independently and simultaneously with French and American cinema, challenging the common narrative that cinema was primarily a French invention. The preservation of variety acts like Schäffer's performance provides invaluable documentation of late 19th-century popular culture and entertainment.

Making Of

The making of 'Der Jongleur' was a pioneering effort in the earliest days of cinema. The Skladanowsky brothers, Max and Emil, had been working on motion picture technology since 1892, developing their Bioscop system in their workshop in Berlin. For this film, they convinced established variety performer Sylvester Schäffer Sr. to participate in their experimental medium. The filming would have taken place in extremely basic conditions, with no artificial lighting beyond what was naturally available. The camera was hand-cranked, requiring careful manual operation to maintain consistent speed. Schäffer would have had to perform his entire act multiple times to ensure the brothers captured usable footage, as early film was expensive and processing was difficult. The brothers developed their own film stock and chemicals, as no commercial film industry existed yet. The entire production process, from filming to developing to projection, was handled entirely by the Skladanowsky brothers themselves.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Der Jongleur' is extremely basic by modern standards, representing the earliest techniques of motion picture photography. The camera is stationary, positioned to capture the full stage performance in a single wide shot. There are no camera movements, cuts, or close-ups - the entire film consists of one continuous take. The lighting is natural and likely uneven, with the performer illuminated from above by theater lights. The framing is centered on the performer, showing him from approximately waist to head height. The image quality would have been grainy and low-contrast by today's standards, but revolutionary for 1895. The cinematography serves a purely documentary function - simply capturing the performance as clearly as the technology of the day would allow.

Innovations

'Der Jongleur' represents several important technical achievements in early cinema history. The film was created using the Skladanowsky brothers' Bioscop system, which was one of the first practical motion picture devices. Their camera used a unique intermittent mechanism that could capture images at approximately 16 frames per second. The Bioscop projector was particularly innovative for its time, using a double lens system that could project two images simultaneously from a single film strip. The film was shot on 54mm film stock, which the brothers had to develop and process themselves. The entire production chain - from camera design to film processing to projection - was created by the Skladanowsky brothers without access to the established film industry that would later develop. While their technology was ultimately superseded by more practical systems, their work demonstrated that motion pictures were a viable technology for public entertainment.

Music

This film was created during the silent era and had no synchronized soundtrack. During its original screenings at the Wintergarten Theatre, the film would have been accompanied by live music, typically a piano or small orchestra playing popular tunes of the era. The musical accompaniment would have been chosen to match the mood of the performance - likely light, upbeat music to complement the juggling act. The theater's regular musicians would have improvised or played appropriate selections from their repertoire. Some early film presentations also included sound effects created backstage or by theater staff, though this was less common for simple documentary films like 'Der Jongleur'.

Memorable Scenes

- The entire film consists of Sylvester Schäffer Sr.'s mesmerizing balancing act, where he skillfully maintains equilibrium of a bowler hat and billiards ball on his arms and body, showcasing the kind of vaudeville entertainment that captivated audiences in the late 19th century and represents one of the first performances ever captured on film.

Did You Know?

- This is one of the very first films ever made in Germany, created just months after the Lumière brothers' first screening in Paris

- The film was part of the very first public film screening in Germany, which took place at Berlin's Wintergarten Theatre on November 1, 1895

- Sylvester Schäffer Sr. was a well-known variety performer in Berlin before being captured on film, making him one of the first film actors in history

- The Skladanowsky brothers' Bioscop projector could show two frames simultaneously by using a double lens system

- This film predates the famous Lumière brothers' screening by several weeks, though the Lumières' technology ultimately proved more influential

- The film was shot on 54mm film, a format unique to the Skladanowsky brothers that didn't become standardized

- Only a few seconds of footage from this film are known to survive today

- The performer's son, Sylvester Schäffer Jr., also appeared in early German films

- The title 'Der Jongleur' is German for 'The Juggler,' though the performance focuses more on balancing than traditional juggling

- This film represents one of the earliest examples of capturing a live performance on camera, establishing cinema as a medium for preserving theatrical acts

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for 'Der Jongleur' and the Skladanowsky brothers' first screening was generally positive, with newspapers marveling at the new technology. The Berlin press reported enthusiastically about the 'living photographs' and praised the novelty of seeing moving images. Critics were particularly impressed by the clarity and realism of the projected images. However, some reviewers noted the technical limitations compared to live performance. Modern film historians recognize 'Der Jongleur' as a historically significant artifact that demonstrates the early cinema's documentary impulse and its fascination with capturing real skills and performances. Scholars appreciate the film for what it represents in the development of cinema technology and as evidence of parallel invention in film history.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences at the Wintergarten Theatre in November 1895 were reportedly astonished and delighted by the Skladanowsky brothers' presentation, which included 'Der Jongleur' among other short films. Contemporary accounts describe gasps and applause from the theater-goers who had never seen moving images before. Many viewers initially couldn't believe their eyes, with some reportedly checking behind the screen to see how the trick was accomplished. The novelty of seeing a familiar performer like Sylvester Schäffer Sr. captured on film added to the wonder. The success of this first screening led to additional performances, though the Skladanowsky brothers' technology was soon overshadowed by the Lumière brothers' more practical system. The audience reaction demonstrated the immediate appeal of cinema as a new form of entertainment.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage magic and illusion shows

- Vaudeville and variety theater performances

- Photographic technology

- Optical toys like the zoetrope and phenakistoscope

This Film Influenced

- Other Skladanowsky brothers films from 1895

- Early Lumière brothers actuality films

- Edison's vaudeville films

- Early documentary shorts capturing performances

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Only fragments of this film are known to survive today. Like many early films from the 1890s, much of the original footage has been lost due to the fragile nature of early film stock and the lack of systematic preservation efforts in cinema's earliest days. The surviving portions are preserved in film archives, likely including the Bundesarchiv in Germany and possibly other international film archives that hold early German cinema. The film exists in deteriorated condition, which is typical for films of this age. Some restoration work may have been done on the surviving fragments, but the complete original film is considered partially lost.