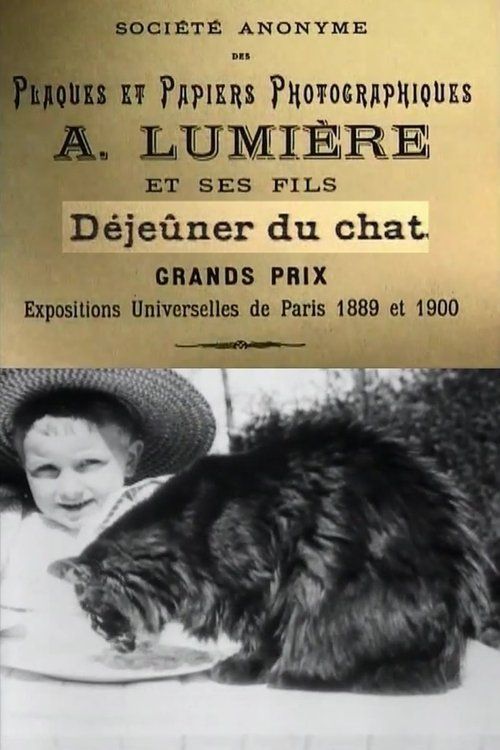

Déjeuner du Chat

Plot

In this brief but charming actuality film from the Lumière brothers, a young boy, identified as Marcel Koehler, carefully carries a small plate of milk across a garden or yard. The boy approaches a large cat that is sitting peacefully on the ground, grooming itself with meticulous attention. The cat pauses its grooming to lap up the milk offered by the child, creating a tender moment of interspecies interaction. The entire scene unfolds in a single, unbroken take, capturing the simple domestic tableau with remarkable clarity for the era. The film concludes as the cat finishes its meal and the boy watches with satisfaction, having successfully provided nourishment to his feline companion.

Director

Cast

About the Production

Filmed using the Cinématographe device, which served as both camera and projector. The film was shot outdoors in natural light, a common practice for early Lumière productions. Like most Lumière films of this period, it was captured in a single take without any editing or special effects. The cat and boy were likely real family pets and members rather than hired actors.

Historical Background

1896 was a pivotal year in the birth of cinema, occurring just months after the Lumière brothers' first public film screening on December 28, 1895, at the Grand Café in Paris. This period marked the transition from optical toys and single-viewer devices to projected motion pictures for mass audiences. The Lumière brothers, Louis and Auguste, were competing with Thomas Edison and other inventors to develop and commercialize motion picture technology. Films like 'Déjeuner du Chat' were part of the new medium's exploration of what could be captured and shown to amazed audiences. The late 19th century was also characterized by rapid industrialization, scientific discovery, and the Belle Époque in France, creating an atmosphere ripe for technological innovation. These early films were often shown in vaudeville theaters, fairgrounds, and special exhibitions as part of mixed entertainment programs.

Why This Film Matters

'Déjeuner du Chat' represents an important example of the Lumière brothers' documentary approach to early cinema, contrasting with the fantastical films of Georges Méliès that would soon follow. As one of the earliest films to capture a simple domestic interaction between a child and animal, it demonstrates the new medium's ability to preserve fleeting moments of everyday life. The film is significant for its role in establishing cinema as a tool for documentation and observation, not just spectacle. It also represents the international appeal of simple, universal themes that could be understood across language barriers - a crucial factor in cinema's early global spread. The film's focus on a tender moment between human and animal also hints at the emotional connections that would become central to narrative cinema development.

Making Of

The film was created during the pioneering days of cinema when the Lumière brothers were experimenting with their new invention, the Cinématographe. Unlike the Edison company's Kinetoscope which required individual viewing, the Lumière device allowed for projection to audiences. The film was likely shot in the garden of the Lumière family home or estate, where many of their early actuality films were made. The production would have been extremely simple by modern standards - setting up the heavy Cinématographe on a tripod, loading the film, and capturing whatever action occurred in front of the lens. There was no artificial lighting, no sound recording, and no editing. The boy and cat were probably not 'actors' in the modern sense but rather family members or local residents going about their normal activities, which the Lumière brothers found worthy of documentation.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Déjeuner du Chat' is characteristic of early Lumière films - a single, static wide shot captured with the Cinématograthe camera. The composition is straightforward and functional, with the action taking place in the center of the frame. The film was shot outdoors using only natural daylight, which creates a soft, even illumination typical of Lumière productions. The camera position is fixed at approximately eye level, creating an intimate but observational perspective on the scene. The image quality, while primitive by modern standards, was remarkably clear for 1896, with sufficient detail to show the cat's grooming movements and the boy's careful handling of the milk plate. There are no camera movements, zooms, or other techniques that would become common in later cinema - the entire 45-second film consists of one continuous take from a single position.

Innovations

The primary technical achievement of 'Déjeuner du Chat' lies in its successful capture of moving images using the Lumière brothers' Cinématographe device. This innovative machine served as camera, developer, and projector, making it more versatile than competing systems. The film demonstrates the early mastery of exposure timing and development processes necessary to produce clear images in 1896. The ability to capture subtle movements like a cat grooming and drinking showed the potential of the new medium for documenting natural behavior. The film also represents an early example of the 35mm film format that would become the industry standard for decades. Its successful projection to audiences helped establish the technical feasibility of public cinema exhibitions.

Music

The film was originally produced as a silent work, as all films were in 1896. During initial exhibitions, it might have been accompanied by live music provided by the venue, typically a pianist or small ensemble playing popular tunes of the era. There was no synchronized soundtrack or recorded audio. Modern restorations and presentations of the film may include newly composed musical accompaniment, but the original viewing experience would have been silent with optional live music.

Memorable Scenes

- The entire 45-second single take showing the boy carefully approaching the cat with milk, the cat pausing its grooming to drink, and the tender moment of interspecies connection captured in one of cinema's earliest surviving records of domestic life.

Did You Know?

- This film is also known by its English title 'The Cat's Lunch' or 'Cat's Breakfast'

- It was one of over 1,400 films the Lumière brothers produced between 1895 and 1905

- The cat in the film appears to be a large domestic cat, possibly a Maine Coon or similar breed

- Marcel Koehler was likely related to the Lumière family or lived near their estate in La Ciotat

- The film demonstrates the Lumière brothers' interest in capturing everyday domestic scenes

- Like many early films, it was originally shown without sound, though exhibitors sometimes provided live musical accompaniment

- The Cinématographe camera used to film this could only hold about 50 feet of film, limiting shots to under a minute

- This film was part of the Lumière brothers' first public screening program on December 28, 1895

- The simple act of feeding an animal was considered novel enough to warrant filming in cinema's infancy

- Early audiences were reportedly amazed by the lifelike quality of the cat's movements on screen

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Déjeuner du Chat' is difficult to document as film criticism as we know it did not exist in 1896. However, early audiences and commentators were generally amazed by the lifelike quality of moving images, with many reports of viewers being startled by the realism of the cat's movements. Modern film historians and critics recognize the film as an important example of early actuality filmmaking and the Lumière brothers' observational style. It is often cited in scholarly works about the birth of cinema as representative of the simple, documentary approach that characterized the Lumière output. The film is valued today for its historical significance and its charming capture of a timeless moment of interaction between child and animal.

What Audiences Thought

Early audiences in 1896 reportedly responded with wonder and delight to films like 'Déjeuner du Chat'. The novelty of seeing moving images of everyday scenes was astonishing to viewers who had never experienced motion pictures before. Many contemporary accounts describe audiences gasping, laughing, or even attempting to interact with the screen images. The simple, universally understandable subject matter of a child feeding a cat would have been particularly accessible to audiences of all backgrounds and nationalities. The film's brevity (under a minute) made it suitable for inclusion in the varied programs of short films that characterized early cinema exhibitions. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives or archives appreciate it as a window into both the origins of cinema and late 19th-century domestic life.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Photography (particularly documentary and snapshot photography)

- The Lumière brothers' background in photographic manufacturing

- 19th-century interest in scientific observation and documentation

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Lumière actuality films featuring animals and children

- Early documentary films focusing on everyday life

- Countless later films depicting human-animal relationships

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved and archived as part of the Lumière Institute's collection in Lyon, France. It has been restored and digitized for modern viewing and is considered one of the better-preserved examples of early Lumière productions. The film exists in the archives of several film institutions worldwide and has been included in numerous retrospectives and collections of early cinema.