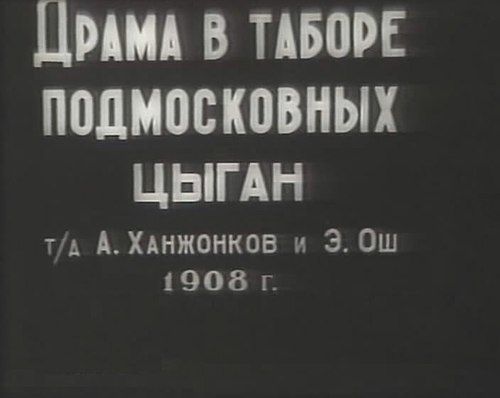

Drama in a Gypsy Camp Near Moscow

Plot

In this early Russian silent drama, two young gypsy lovers steal away from their camp near Moscow under the cover of night for a private rendezvous. The young man passionately declares his love and proposes marriage to his beloved, but she refuses his advances for reasons left unstated. Overcome with jealous rage and despair at her rejection, the man pulls out a knife and brutally murders the woman on the spot. Her body is discovered almost immediately by other members of the gypsy camp, who raise an alarm. Consumed by guilt and grief over what he has done, the distraught murderer flees to a nearby cliff and throws himself off, plunging to his death on the rocks below.

Director

Vladimir SiversenCast

About the Production

This film was produced during the very early days of Russian cinema, when films were typically only a few minutes long and shot on location with minimal equipment. The production would have used hand-cranked cameras and natural lighting. The cliff scene was likely performed by a stunt double or created through camera tricks, as safety equipment was virtually non-existent in 1909.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a fascinating period in Russian history and cinema. 1909 was just two years after the 1905 Revolution had shaken the Russian Empire, and social tensions remained high. The film industry in Russia was still in its infancy, with Alexander Khanzhonkov having only established his studio in 1906. Russian cinema of this era was heavily influenced by French films, particularly those from Pathé, but was beginning to develop its own distinct style. The portrayal of gypsy life reflected a long-standing Russian fascination with Roma culture, which was often romanticized in literature and art. This film emerged during the reign of Tsar Nicholas II, just a few years before the massive social changes that would lead to the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest examples of Russian narrative cinema, this film holds immense historical importance despite its short length. It demonstrates how early Russian filmmakers were already exploring complex themes of passion, violence, and psychological drama. The film's depiction of gypsy culture reflects the romanticized view of Roma life that was common in Russian art and literature of the period. Its existence shows that Russian cinema quickly moved beyond simple actualities and trick films to embrace narrative storytelling. The film also represents an early example of the crime genre in Russian cinema, predating the more famous Russian crime films of the 1910s and 1920s. Its preservation allows modern viewers to glimpse the very beginnings of what would become one of the world's most important cinematic traditions.

Making Of

The production of this film in 1909 would have been rudimentary by modern standards. Vladimir Siversen would have directed using a hand-cranked camera, with no ability to record sound. The actors, including Pyotr Chardynin, would have relied on exaggerated gestures and facial expressions to convey emotion, as intertitles were minimal in early Russian cinema. The gypsy camp was likely filmed on location near Moscow with real Roma people as extras. The murder scene would have used stage blood and careful camera positioning to create the illusion of violence without actual harm. The cliff jumping scene presented the greatest technical challenge - it may have been filmed using a double, camera tricks, or possibly even involved real danger to the performer. The entire film would have been shot in sequence, as editing capabilities were extremely limited in 1909.

Visual Style

The cinematography of this 1909 film would have been rudimentary but effective. The camera would have been stationary for most scenes, as mobile cameras were not yet in common use. Natural lighting would have been used for outdoor scenes, while interior or night scenes would have relied on whatever artificial lighting was available. The film was shot in black and white, with no color tinting mentioned in surviving records. The camera work would have been functional rather than artistic, focused primarily on capturing the actors' performances. The cliff scene may have used long shots to establish the dangerous setting, followed by medium shots of the actor's preparation to jump. Given the technical limitations of 1909, the cinematography prioritized clarity and visibility over artistic expression.

Innovations

While technically simple by modern standards, this film represented several achievements for Russian cinema in 1909. The successful creation of a coherent narrative in just a few minutes demonstrated advanced storytelling techniques for the era. The filming of the cliff scene, whether through stunt work or camera tricks, showed innovation in creating dramatic action sequences. The production's ability to shoot on location at a gypsy camp indicated growing sophistication in Russian film production. The film's use of dramatic violence and psychological themes pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable content in early cinema. The preservation of the film itself is a technical achievement, given the fragile nature of early film stock.

Music

As a silent film from 1909, this movie had no synchronized soundtrack. During theatrical exhibition, it would have been accompanied by live music, typically a pianist or small ensemble in the cinema. The music would have been improvisational or based on popular classical pieces that matched the mood of each scene - romantic music for the lovers' meeting, dramatic and dissonant sounds for the murder, and mournful melodies for the suicide. Some cinemas might have used sound effects like drums or cymbals to accentuate dramatic moments. The choice of music would have been left to individual cinema musicians, meaning each screening could have a different musical interpretation.

Famous Quotes

No recorded dialogue exists as this is a silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic cliff jumping scene where the murderer, consumed by guilt after killing his beloved, leaps to his death - this would have been one of the most dramatic and technically challenging sequences in early Russian cinema, requiring either dangerous stunt work or clever camera tricks to achieve the desired effect.

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest surviving examples of Russian narrative cinema, predating even many famous early American films.

- Director Vladimir Siversen was one of the pioneers of Russian cinema, though he remains less famous than contemporaries like Yevgeni Bauer.

- Pyotr Chardynin, who stars in this film, would later become one of Russia's most important silent film directors.

- The film was produced by Alexander Khanzhonkov's company, which was the first major film studio in the Russian Empire.

- At only 3-5 minutes long, this was considered a feature-length film for its time.

- The portrayal of gypsy life in early Russian cinema often romanticized or exoticized Roma culture, as seen in this film.

- The film's violent content was quite shocking for 1909, even by the standards of early cinema which often included melodramatic violence.

- This film represents an early example of the crime genre in Russian cinema.

- The cliff scene would have been particularly dangerous to film in 1909, requiring innovative camera techniques or dangerous stunt work.

- The film was likely shot on 35mm film, which was the standard format of the era.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of this film is difficult to determine due to the scarcity of surviving Russian film publications from 1909. However, films from Khanzhonkov's studio were generally well-received by the urban audiences of Moscow and St. Petersburg. The dramatic content and gypsy setting would have appealed to Russian audiences' taste for melodrama and exoticism. Modern film historians view this film as an important artifact of early Russian cinema, demonstrating the rapid development of narrative filmmaking techniques in the Russian Empire. Critics today appreciate it as a window into the aesthetic values and storytelling approaches of Russia's first generation of filmmakers.

What Audiences Thought

Early Russian audiences of 1909 would have been captivated by this film's dramatic story and exotic gypsy setting. At a time when most films were brief actualities or simple comedies, a narrative film with such intense emotional content would have been particularly compelling. The gypsy theme resonated with Russian audiences who had a long-standing cultural fascination with Roma people, often viewing them as symbols of freedom, passion, and mystery. The film's violent conclusion, while shocking, would have provided the dramatic payoff that early cinema audiences craved. The short runtime made it ideal for the variety-style film programs of the era, where multiple short films were shown in succession.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French melodramas of the 1900s

- Russian literary traditions about gypsies

- Early Pathé films

- Stage melodramas

This Film Influenced

- Later Russian crime dramas

- Early Soviet melodramas

- Films featuring Roma characters in Russian cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of this extremely early Russian film is uncertain. Many films from this era, particularly Russian productions from before the Revolution, have been lost due to the fragility of early film stock, political upheavals, and the lack of systematic preservation efforts. If copies do survive, they would likely be in Russian film archives such as Gosfilmofond or international archives specializing in early cinema. The film's survival would be remarkable given its age and the tumultuous history of the 20th century in Russia.